Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching

Volume 15 (2024) Issue 1

pp. 51-77

Learning How to Use Input-Based and Output-Based Form-Focused Instruction: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Korean and Persian EFL Learners

Andrew Schenck (Fort Hays (KS), USA)

Abstract

Although Form-Focused Instruction (FFI) has been extensively investigated, the degree to which grammatical difficulty impacts input-based and output-based FFI approaches has yet to be well defined in an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) context. To address the need for further research, 36 experimental studies were selected for metanalysis (18 studies with Korean EFL learners and 18 studies with Persian EFL learners). The effects of the type of instruction (input vs. output) were analysed along with other variables that may affect acquisition (complexity of a target feature and L1). The results suggested that input-based instruction was more effective for smaller phrasal features, while output-based instruction was more effective for features with more complex clauses (e.g., relative clauses or conditionals). Regarding the L1, output-based emphasis of collocations was more effective with Persian EFL learners, whose L1 shares more morphosyntactic similarities with English. Collectively, both L1 and L2 may determine the efficacy of FFI.

Keywords: Form-focused instruction, EFL, grammar, Korean, Persian

1 Introduction

Focus on form is a pedagogical technique for language instruction that emphasises grammar through “occasional shift of attention to linguistic code features – by the teacher and/or one or more students” (Long & Robinson 1998: 23). To date, several different types of focus on form have been developed. While they all share a common purpose, they differ with respect to how “occasional” the shift of attention is. Some techniques such as input flood, which denotes the placement of a larger number of target features in a text, and input enhancement, which utilises underlining or highlighting of grammatical features in a text, provide a minimally intrusive method to focus attention on grammar.

While minimally intrusive, techniques like input-flood or input-enhancement may also be minimally effective in increasing the accuracy of production. These techniques often yield inconsistent results (Rassaei 2012). Some studies suggest that enhancing input with bolding, underlining, and italicising aids in language acquisition (Alanen 1995, Jourdenais et al. 1995, Lee 2007, Rassaei 2015, Sarkhosh et al. 2013), whereas other studies suggest that it has little to no impact (Cho 2010, Lee & Huang 2008, Leow et al. 2003). Concerning input flood, the results of previous research report variable degrees of effectiveness (Rassaei 2012). The variability of results in studies that use the same type of Form-Focused Instruction (FFI) may suggest that other background influences are involved. If these influences are better understood, the true potential of both input enhancement and input flood could be realised, thereby allowing educators to effectively use the techniques on a consistent basis.

In addition to input enhancement and input flood, attention may also be focused on a grammatical feature through an input-based technique called Processing Instruction (PI). This pedagogical strategy helps learners to identify a relationship between form and meaning through structured input activities (Soruç 2018). The technique is executed in three steps:

providing information about the target linguistic form or structure

informing learners about input processing strategies that may negatively affect the target structure, and

carrying out input-based activities that help the learner understand and process form during comprehension

(Nassaji & Fotos 2011: 24).

To understand the negative evidence provided to help learners process input, we can examine the Lexical Preference Principle by VanPatten (2004). This principle, part of the Primacy of Meaning Principle, suggests, for example, that the past -ed will be acquired later than lexical features. Consider the following example:

The boy studied English yesterday.

In this example, the learner is thought to concentrate on units imbued with more semantic meaning (verbs, nouns, adjectives, and adverbs) over the systematic and redundant past -ed. Since the lexical adverb yesterday already denotes the past, the regular past tense of the verb becomes redundant in this sentence. Using this principle for input processing, learners are helped to understand the difficulty of learning the past -ed. First, they are given information about the target feature and potential learning difficulties. Next, they are provided with tasks that require an understanding of the correct structure in order to understand meaning (Benati 2005, Uludag & VanPatten 2012). As an example, learners may be asked to listen to sentences and choose whether the actions they describe happened yesterday or today.

Like other forms of FFI, the results of PI have yielded mixed results. A study by Benati (2005), for example, revealed that PI had a significant effect on accuracy in written production when the regular past tense was emphasised (Benati 2005). Concerning this study, Benati (2005) concluded that

PI has clearly altered the way learners processed input and this had an effect on their developing system and subsequently on what the subjects could access for production. (ibid.: 83)

Although compelling, the results of the study revealed that scores for the PI group were only higher on the interpretation task. Production tasks for the PI group were less accurate than those from either the traditional (explicit) or meaning-based instruction groups. Similar findings were revealed in another study of Russian prepositional phrases, whereby traditional pattern drills had a larger impact on productive tasks than Processing Instruction (Comer & de Benedette 2011). VanPatten (2014) has used such lacklustre results for Processing Instruction in production to conclude that explicit instruction is largely superfluous. The variability of results, however, may suggest that contextual factors influence the efficacy or inefficacy of different forms of FFI. Therefore, further study is needed.

2 Using Output for FFI

While the modification of input is one viable means of focusing attention on a grammatical feature, it is not the only one. Swain (1998) pointed out that having students produce output can enhance the noticing of a grammatical feature. Speaking and writing can also allow the learner to test hypotheses about a grammatical feature or use ‘metatalk’ about linguistic features to reflect on language use (Swain 1998). Several studies suggest that promoting output helps learners to acquire grammatical features and vocabulary (Izumi 2002, Rassaei 2012, Shintani 2011). In a study of 129 Persian learners, output had the most significant impact on writing production of so and such clauses, outperforming text enhancement, input enrichment, and control groups on both immediate and delayed posttests (Rassaei 2012). In a study of English relative clauses, Izumi (2002) found that learners who engaged in output activities outperformed learners who received visual input. The study led researchers to conclude that “no support was found for the hypothesis that the effect of input enhancement was comparable to that of output” (ibid.: 542).

As in the case of input-based instruction, studies of output-based instruction often yield inconsistent results. Shintani (2011) found that both input-based tasks for comprehension and output-based tasks for production had positive effects. However, input-based tasks enhanced interaction, leading to improved performance on a comprehension test. Benati (2001) also found that input-based tasks increased performance more significantly than output-based tasks that use explicit grammar rules with follow-up writing or oral practice. Some research even suggests that output-based emphasis of grammatical features is largely superfluous. In a study by Izumi & Bigelow (2000), output-based tasks did not have a significant impact. Follow-up research further suggested that

the output task failed to engage learners in the syntactic processing that is necessary to trigger L2 learning, while the task for the nonoutput group appeared to promote better form-meaning mapping. (Izumi & Bigelow 2000: 587).

3 Reasons for Variability in Results: A Closer Look at Grammatical Features

The results of both input-based and output-based instruction show a great deal of inconsistency, leading to confusion about precisely how and when a specific type of FFI should be used. In reality, there are a number of other contextual variables that also influence the acquisition process, thereby affecting whether or not an instructional intervention is effective. The type of grammatical feature, for example, has a large impact on morphosyntactic development, as well as the efficacy of FFI (Dyson 2018, Dyson & Håkansson 2017). Regarding grammar, past studies have relied on overly simple binary classifications, suggesting that target features can be divided into just two categories: lexical or systematic (Wang & Jiang 2015). Although this is indeed an important distinction, it oversimplifies the features of grammar that influence FFI. As revealed by the Processability Theory, grammatical features are more complicated than simple binary classifications would suggest (Pienemann & Lenzing 2015).

In addition to systematic and lexical characteristics, the complexity of phrases or clauses associated with each target feature helps to determine when grammar is acquired. According to the Processability Theory, grammatical features may be separated into three main types.

The first type of grammatical feature is intra-phrasal, meaning that a single word or phrase must be modified for construction. An example of this type of feature would be when a noun phrase, like car, receives a plural marker to become cars. Due to the relative simplicity of intra-phrasal features, they tend to be acquired early in the process of L2 development.

The second type of grammatical feature is called inter-phrasal, because it requires the manipulation of multiple phrases for construction. An example would be when an auxiliary verb is inverted with the subject noun phrase in a yes/no question (e.g., Can you hand me a pen?). Another example would be the addition of a third person singular -s morpheme, which requires an inter-phrasal understanding of the relationship between the subject and verb for correct conjugation (e.g., He eats). Due to heightened complexity, inter-phrasal grammatical features tend to be acquired later than their intra-phrasal counterparts.

The final type of grammatical feature is clausal, meaning that multiple clauses must be manipulated for construction. An example of this type of grammatical feature would be the past hypothetical conditional, which requires the creation of both a main and subordinate clause (e.g., If I hadn’t drunk too much last night, I wouldn’t have missed class). Due to the morphosyntactic complexity of clausal features, they tend to be acquired last (Pienemann 2005).

As revealed by the elements of the Processability Theory, increased grammatical complexity may have a significant impact on acquisition, suggesting that learners need to be at a certain proficiency level in order to benefit from FFI that is focused on a specific target feature (Gholami & Zeinolabedini 2018).

Like grammatical complexity, L1 differences can impact how easily a grammatical feature is acquired. When Spanish EFL students learn target features like the English definite article, for example, which is similar to the L1, they outperform counterparts from countries like Japan, Korea or China, who lack this particular feature in their native languages (Luk & Shirai 2009). In addition to morphological features, the acquisition of syntactic features appears to be influenced by a learner’s L1. Persian EFL learners, for example, whose L1 is largely head-final, tend to read and comprehend texts more slowly than their Turkish counterparts, who use a head-initial L1 like English (Maleki 2006). Korean learners, whose language shares the head-final parameter found in Persian, also tend to have more difficulty processing and acquiring head-initial English syntax (Shin 2015). Overall, there is a great deal of research suggesting that both morphological and syntactic features are influenced by a learner’s L1 (Yang et al. 2017).

Past studies of FFI have variable results, preventing educators from practically applying FFI techniques in a consistently effective way. These inconsistencies reflect weaknesses in the design of past experimental research, which utilised oversimplistic classifications for variables that influence L2 development. In reality, the impact of diverse grammatical features, along with associated influences from the L1, are more complex than past studies would suggest. Modern studies recognise these fundamental weaknesses, calling for more qualitative studies that can explore multiple influences of second language acquisition (De Costa, Gajasinghe, Ojha & Rabie-Ahmed 2022, Lee 2019). While qualitative analysis can provide a more holistic view of multiple variables, so may meta-analysis, which collates past experimental studies, allowing for comparison. Through comprehensive analysis of many past experimental studies, a more holistic perspective may be obtained, which can help educators understand how and when different types of input-based or output-based FFI techniques should be used.

4 Research Questions

The present meta-analysis was designed to investigate grammatical difficulty and its impact on the efficacy of input-based and output-based instruction. Since grammatical difficulty cannot be defined without consideration of both grammatical complexity (intra-phrasal, inter-phrasal, and clausal) and L1 differences, selected studies of input-based and output-based instruction examined a variety of grammatical features, along with learners at diverse developmental levels who had two different L1s: Korean and Persian. The following questions were posed to guide our examination:

1. What types of instruction (input-based or output-based) are most effective with each type of grammatical feature (intra-phrasal, inter-phrasal, and clausal)?

2. Does the effectiveness of an instructional type (input-based or output-based) differ according to the similarity of a target feature to the L1?

Through investigating the questions above, it was hoped that a holistic understanding could be obtained to reform curricula or enhance automated language learning systems, thereby tailoring instruction to learner needs.

5 Method

In accordance with a need for further research, the present meta-analysis was designed to examine the impact of variables like grammatical complexity (intra-phasal, inter-phrasal, and clausal), type of instruction (input-based vs. output-based), and learner L1 on accuracy of production in speech or writing. To obtain studies of EFL learners from each target L1, Google was systematically searched by using the keywords Korean or Persian with various search terms for grammatical features (plural, past tense, past regular, past irregular, passive, third person, questions, article, definite article, indefinite article, phrasal verb, verb particle, conditional) and types of FFI treatments (form-focused instruction, focus-on-form, focus-on forms, PI, text enhancement, dictogloss, output, input, control group). Following the search, full texts for each study were obtained for further examination.

There are key differences between explicit knowledge and actual performance in production (implicit knowledge). Therefore, only studies that elicited responses in speech and writing were selected. To ensure that production reflected implicit knowledge of a target feature, studies had to use language assessments that communicated ideas, not rules. The assessments also needed to put pressure on learners to prevent conscious correction of language errors. Finally, the assessments needed to focus on meaning and avoid the use of metalanguage (Ellis 2009). In order to be included within the present meta-analysis, each experimental study needed to have:

An input-based or output-based treatment (including time for treatment and methods of delivery)

Pretest and Posttest measures of production (either oral or written)

Information about the type of grammatical feature targeted, and

Participants that used only one target L1 exclusively (Korean or Persian)

Out of all the studies examined for Korean learners, 59 experimental studies were located. From this group, only 18 studies met the criteria for inclusion. Many studies lacked adequate assessment of productive, implicit knowledge, leading to their exclusion (Appendix A for more information on selected studies). Concerning Persian learners, 89 potential studies were located. Out of these studies, only 18 could be used (Appendix B for more information). In addition to problems with assessment of production, some studies lacked sufficient knowledge to understand the methodology or length of treatment. Thus, they were excluded. In toto, the present meta-analysis contained 36 studies for analysis.

5.1 Grammatical Feature Type

Once the studies had been compiled, the results of each study were organised and evaluated according to grammatical features. The types of grammatical features were grouped for comparison. As revealed by the Processability Theory, grammatical complexity could vary based on whether a target feature is intra-phrasal (e.g., verbs and associated morphological features like the regular past -ed), inter-phrasal (e.g., question inversion or phrasal verbs), or clausal (e.g., cancel inversion) (Pienemann & Lenzing 2015). Grammatical features from studies of Korean and Persian learners in Appendices A and B were separated as in Table 1:

In total, 88 treatment groups were obtained from the selected studies. As nine of the control groups contained collocations with more than one grammatical feature from a different complexity level, these treatment groups were excluded from the analysis of grammar type, leaving a remainder of 79 treatment groups.

5.2 L1 Influence

In order to investigate the influences of L1 on the acquisition of English grammatical features, EFL learners with two native languages, Korean and Persian, were studied. There were 88 treatment groups in total (41 Persian and 47 Korean). These languages differ in how closely their grammar resembles English. Being from the Altaic language family, Korean grammar tends to differ more significantly from its Persian counterpart when compared to English. Overall, Persian appears to share more lexical, morphological, and syntactic attributes with English, which are factors that may influence how a second language is acquired (Luk & Shirai 2009, Maleki 2006, Shin 2015).

Although both Korean and Persian share an SOV word order and lack question inversion, they differ significantly in how other grammatical features are used. These differences appear to reflect a Persian connection to the Indo-European language family, as well as an ancestral link to English. In Persian conditionals, for example, the Persian word for if is a free morpheme that is generally used at the beginning of the conditional clause, followed by a main clause which uses the future tense. Despite Persian being a head-final language in sentence structure, the if-marker appears at the beginning of the conditional clause, as in English (Abdollahi-Guilani et al. 2012). In contrast to both Persian and English, the Korean conditional is bound to a head-final parameter.

Concerning verb tense, Persian also parallels English in a number of ways. It uses a past tense verb that is completely different from the present form (similar to lexical past in English) (Persian in Context 2013: 9). Concerning the future tense, it

is used almost exactly like the English future tense; the only difference being that it is also very common in Persian to use the present tense for expressing future actions. (Mazdeh 2013: para. 1)

Concerning aspect, Persian is similar to English in usage. The present perfect aspect, for example, adds a present copula to the past participle, which parallels the English form. This similarity suggests that “By and large, the Persian present perfect, sometimes referred to as past narrative, corresponds to the English present perfect” (Grammar and Resources 2007: para. 3). Korean verb tenses for the simple past also resemble English in some ways, having regular past forms to add the past meaning. Despite such similarity, the present perfect and present perfect progressive tenses lack equivalent morphosyntactic structures in Korean. Instead, Korean uses a variety of morphological verb endings and adverbials to express aspect, making it highly different from its Persian counterpart in regard to this morphosyntactic feature.

Both English and Persian have an article system. Unlike English, however, only the indefinite article is used in Persian. Nouns that do not have an indefinite article are considered to be definite (Momenzade & Youhanaee 2014: 1187-1188). Korean lacks the English article system entirely. Instead, learners express definite articles through modifiers like demonstrative pronouns and the indefinite article by numeric modifiers (Lee 1999: 37).

Persian relative clauses are head initial, as in English. However, there is a difference in the word order of the constituents in the Persian relative clause. In contrast to both Persian and English, Korean relative clauses use the head-final attribute. This factor, along with morphological differences in the use of relative clauses in Korean, suggests that it is more highly disparate from English.

Overall, the comparison of the two languages suggests that Persian has more grammatical similarities than its Korean counterpart in regard to English. This is not surprising, given that both English and Persian are Indo-European languages, whereas Korean is from the Altaic language family. Due to the distinct differences, these two languages were used as a variable to examine the influence of L1 similarity on the effectiveness of FFI. Persian and Korean language learners were separated for analysis so that the influence of L1 similarity on the acquisition of English grammatical features could be assessed.

5.3 Input-Based Output-Based Definitions

Studies designed to evaluate the efficacy of either input or output were selected and separated based on instructional type (Appendix C for more information about treatments). Those studies that had a major emphasis on both input and output in the FFI treatment were excluded from the analysis. Whereas treatments primarily designed to emphasise the impact of input (e.g., input flood, IE, and PI) were assigned to the input category, tasks that emphasised output (e.g., text reconstruction or dictogloss) were assigned to the output category. The input vs. output distinction was used to analyse differences in effect sizes, along with variables such as grammatical complexity and learner L1. For input, there were a total of 52 treatment groups; for output, there were a total of 36 groups.

Overall, output-based treatments included a variety of both written and spoken tasks. As an example, a study by Fakharzadeh & Youhanaee (2012) included individual text reconstruction, close translation, and a dictogloss. Among these tasks, production in the form of writing may be expected, along with verbal production associated with the dictogloss. Metatalk may also be expected, as learners share information about a story to reconstruct a text. Other studies of output-based assessments like that of Kim (2014) utilised images to elicit verbal responses about a target feature. With the exception of studies that used only the dictogloss, there was little standardisation of the techniques used to elicit output. While forms of production did vary, Swain (1998) points out that all production tasks give learners the ability to use and test hypotheses about a target feature. Some output groups did include a degree of explicit information or guidance to conduct the activity, which was a type of input. In each treatment, however, the emphasis was on producing output rather than providing input. Studies that used a dictogloss, for example, required input before the story was reconstructed. However, the main goal of the activity was output, as reflected by procedures that included note taking, meta-talk, and story construction. Although some input may have been provided with output treatment groups, the main goal of these groups was to generate either an oral or written product. Therefore, a clear emphasis was placed on production, rather than input, allowing learners time to test hypotheses as envisioned by Swain (1998). Some studies provided an emphasis on both input and output in the same treatment groups. These treatment groups were excluded from the analysis. Control groups with no treatment were also excluded from the analysis.

5.4 Procedure

In order to compare results from individual studies, effect sizes needed to be calculated for each study. Whereas p-values reveal whether results are significant (not a result of chance), effect sizes determine the magnitude of a difference between groups (Sullivan & Feinn 2012). Since significant p-values may not actually reveal a large effect (e.g., large numbers of participants or amounts of data may cause even a small difference to be significant), effect size is needed to understand how impactful a treatment is. Calculating the effect size also provides a consistent way to compare different studies, since the calculations are standardised measures.

Cohen’s d was used to calculate effect size, as in the study by Spada & Tomita (2010), which analysed effects of explicit and implicit instruction on the acquisition of simple and complex grammatical features in English. In the current study, effect size was calculated by inserting pretest scores (M2), posttest scores (M1), and associated standard deviations (SD2 and SD1) into the Cohen’s d formula for effect size (Spada & Tomita 2010: 307):

d = [M1 - M2] / [SQRT[(SD1SD1 + SD2SD2]/2]

After calculating the effect sizes for each treatment group, the results were collated based upon the variables, allowing for further analysis. For grammatical complexity, for example, effect sizes were collated based upon whether an intra-phrasal, inter-phrasal, or clausal feature was emphasised. For L1, effect sizes were collated based upon the use of either Korean or Persian learners. The results were then broken down by type of instruction (input or output) for further analysis.

6 Results and Discussion

6.1 Target Feature-based Instruction

The first research question aimed to investigate the effects of grammatical feature type on the efficacy of FFI. Results were first analysed according to categories of grammatical complexity suggested by the Processability Theory: intra-phrasal, inter-phrasal, and clausal. The comparison of grammatical complexity with the type of instruction suggested that output-based instruction is more effective when more complex, clausal features are emphasised (Table 2). At the more complex clausal level, the difference in effect was .48. Because prior research of meta-analysis suggests that a small effect size is d >0.2, a medium effect size is d >0.5, and a large effect size is d<0.8 (Rice & Harris 2005), the difference between input and output-based instruction for clausal features is sizable, representing a small, yet nearly medium difference in effect:

Table 2: Average Effect Size by Grammatical Complexity and Type of Instruction

Input-based instruction was more effective for phrasal grammatical features. At both the intra and inter-phrasal level, the difference in effect size was similar. At the intra-phrasal level, input-based instruction was more effective by .09; at the inter-phrasal level, input-based instruction was more effective by .10.

Regarding Research Question 1, which attempted to discern the impact of FFI on diverse grammatical features, the results suggest that more complex clausal target features benefit more from output-based instruction. In contrast, intra- and inter-phrasal features appear to benefit more from input-based instruction. This finding may reveal that instructional styles can be carefully selected based upon the target feature to maximise acquisition. Input-based instruction may better assist beginning or intermediate learners who are presented with activities targeting intra- or inter-phrasal features. In contrast, more complex clausal features may be served by output that pushes learners to speak or write. Clausal features have more constituents that must be ordered syntactically, which may explain why production has a larger effect. Production may activate a syntactic encoder, promoting better acquisition of syntactically complex features.

Intra- and inter-phrasal features included largely lexical and morphological features. These features appeared to benefit more from input-based instruction. Combined verb tenses, collocations, modals, and comparative adjectives from these categories, all these benefited more from input. The passive, which also benefited more from input-based instruction, has many lexical elements. In the case of a sentence like The book was written, for example, the past auxiliary (was), and the past participle (written) must be lexically retrieved. If the main verb is regular, the morphological ending -ed must be attached, adding further complexity to the feature. In the case of grammatical features that are lexically complex, input-based instruction may prime the learner by providing information for form/meaning mapping, which facilitates the correct use of lexical structures associated with these features. By combining several elements together, the scope and complexity of a target feature increases, which may require a scaffold in the form of additional input.

It is possible that input provides assistance with form-meaning mapping or simplistic binary morphological features like the past -ed. Input may provide scaffolding early in the acquisition process. As the complexity of syntax increases, output-based instruction may more effectively push learners to arrange syntactic elements into the correct word order. Essentially, input or output may emphasise different characteristics of grammar. Since the difficulty posed by lexical variation or syntactic complexity is also determined by the L1, characteristics of the learner must be further studied to clarify the impact of input and output-based instruction.

6.2 Influence of L1 on Effectiveness of FFI

Research Question 2 attempted to ascertain the influence of L1 differences. Overall, Persian learners had higher effect sizes than their Korean counterparts. This finding may suggest that language acquisition is hastened by similarities between the Persian L1 and English L2, which both belong to the Indo-European language family.

While both Persian and Korean learners benefited more from input (Table 3), the difference between input and output-based instruction for Korean learners (difference of .30) was much larger than that for Persian learners (difference of .09). Since the Korean L1 is more highly dissimilar from English as an L2, this finding may suggest that input-based instruction is more effective with target features that differ more significantly from the L1:

When the same target features were emphasised, effect sizes tended to be larger for Persian FFI interventions (Figure 1):

Figure 1: Input and Output-Based Instruction for the Same Grammatical Feature in Persian and Korean

Except for the conditional feature, effect sizes for Persian learners were more than double than those of their Korean peers. Our results may suggest that L1 similarities to English have impacted the effect size. Each of the L2 grammatical features in Figure 1 is more similar to Persian than Korean (Section 5 for more information).

Although the impact of FFI seems to be less substantial for Korean EFL learners, the effects of input and output-based instruction for each grammatical feature appear consistent across the groups (with the exception of collocations). Input-based instruction tended to be more effective, albeit slightly, for the conditional and verb tenses than output-based instruction. In contrast, output-based instruction seemed to be more effective for relative clauses. Only lexical categories and collocations differed across the groups. For Korean learners, collocations had a higher effect size when input-based instruction was used (d=2.58). This value led to a sizable difference from output-based instruction of 1.31. Persian learners, in contrast, benefited more from output-based instruction when collocations were emphasised (d=5.44). The resulting difference is also substantial, leading to a gain of 1.07. L1 similarities may explain why collocations had higher effect sizes for Persian EFL learners. Whereas input provides exemplars, output requires learners to produce collocations without assistance. Due to common lexicogrammatical forms from the Indo-European language family, Persian collocations or cognates may promote transfer, thereby negating a need for exemplars within the input.

While L1 similarity or difference appears to have influenced the effect size, other factors may also have influenced the results. Korean studies appear to reveal a larger duration for treatment with conditionals, which seems to suggest that the higher effect sizes among Persian learners are the result of L1 transfer. However, three out of the five Korean studies examined the third (past hypothetical) conditional (Kang 2011, Song 2007, Song & Suh 2008), whereas two studies examined the second (present unreal) conditional (Kang 2003, Shin 2011). In the Persian study by Khani & Davaribina (2013), only the first and the second conditional structure was emphasised. Using FFI with only first and second conditional features may have resulted in a larger effect size, explaining why Persian learners outperformed their Korean counterparts in regard to this target feature. Concerning other grammatical features, the effects of L1 similarity and duration were difficult to interpret. Both relative clauses and verb tenses were more highly similar to the Persian L1 and of higher duration in the Persian studies examined (Appendices A and B for more information about duration). Such an inability to discern the potentially synergistic effects of both duration and L1 reflects a need for further research.

7 Conclusions

The present meta-analysis sought to examine the influence of input and output-based instruction, as well as other mitigating factors impacting the efficacy of FFI (grammatical complexity and L1). The results revealed that the success of input- vs. output-based instruction is highly dependent upon grammatical difficulty, which is ultimately defined by characteristics of the grammatical feature, along with characteristics of a learner’s L1. Concerning grammatical difficulty, the results suggest that intra-phrasal, inter-phrasal, and clausal attributes attributed to Pienemann’s Processability Theory influence the efficacy of FFI. More complex clausal features, like the relative clause, appeared to benefit more from output-based instruction, which forces learners to put constituent parts in a specific sequence. Grammatical features at the intra- and inter-phrasal levels benefited from more input-based instruction. Input may provide form-meaning mapping required for better acquisition of phrasal features, which are largely morphological and lexical.

L1 and L2 differences also appear to influence the efficacy of FFI, as well as the type of instruction which is most effective. Overall, studies with Persian EFL learners had higher effect sizes. Having an Indo-European language, Persian learners may share common collocations or grammatical features that facilitate transfer. Concerning the relative clause, for example, a head-initial component makes it more like English than Korean, which uses a head-final noun at the end of a relative clause. Although Persian learners tended to benefit more from FFI, the effects of instruction appeared similar based upon the target feature. Input-based instruction tended to be more effective than output-based instruction for the conditional and verb tenses; output-based instruction appeared to be more effective for relative clauses. Only lexical categories and collocations differed across the groups. The disparity from collocations may suggest that L1 transfer makes input less necessary for Persian EFL learners.

The results of the study provide information that may be useful to educators, yet limitations still exist concerning the degree to which research may be adapted to practice. As existing experimental studies often examine similar grammatical features with learners at similar English proficiency levels, the degree to which timing determines effectiveness of FFI is still unknown. Furthermore, past experimental studies selected for meta-analysis used different treatments and assessments that may have impacted the results. In the future, more controlled experimental or qualitative research is needed to provide an even more holistic perspective of FFI. With such a perspective, theory may finally be applied to practice. Educators may then be able to provide effective pedagogical techniques at the right time, thereby tailoring instruction to the needs of diverse learners.

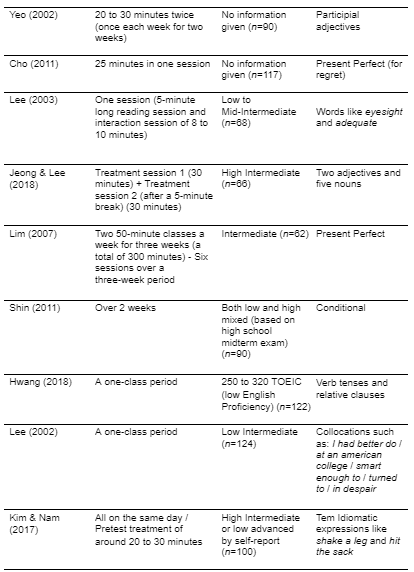

Appendix A

Appendix B

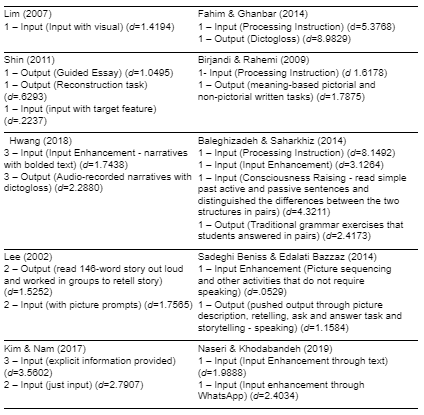

Appendix C

References

Abdollahi-Guilani, Mohammad, et al. (2012). A Comparative analysis of conditional clauses in English and Persian: Text analysis. 3L: Language, Linguistics,Literature, 18(2), 83-93. https://ejournal.ukm.my/3l/article/view/938

Alanen, Riikka Aulikki (1995). Input enhancement and rule presentation in second language acquisition. In Richard Schmidt (Ed.), Attention and awareness in foreign language learning (pp. 259-302). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Azmoon, Yasaman (2021). Dictogloss or Processing Instruction: Which Works Better on EFL Learners’ Writing Accuracy?. Porta Linguarum, 36, 263-277. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.v0i36.20909

Baleghizadeh, Sasan & Arash Saharkhiz (2014). An investigation of spoken output and intervention types among Iranian EFL learners. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 5(12), 17-41.

Benati, Alessandro (2001). A comparative study of the effects of processing instruction and output-based instruction on the acquisition of the Italian future tense. Language Teaching Research, 5(2), 95-127. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216880100500202

Benati, Alessandro (2005). The effects of processing instruction, traditional instruction and meaning— output instruction on the acquisition of the English past simple tense. Language Teaching Research, 9(1), 67-93. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168805lr154oa

Birjandi, Parviz & Jamileh Rahemi (2009). The effect of processing instruction and output-based instruction on the interpretation and production of English causatives. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 12(2), 1-30. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-50-en.html

Birjandi, Parviz et al. (2011). VanPatten's processing instruction: Links to the acquisition of the English passive structure by Iranian EFL learners. European Journal of Scientific Research, 64(4), 598-609.

Cho, Min Young (2010). The effects of input enhancement and written recall on noticing and acquisition. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 4(1), 71-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501220903388900

Cho, Yunkyoung (2011). Effects of different types of focus-on-form instruction and learner readiness on the learning of perfective modals. Foreign Languages Education, 18, 1-27.

Comer, William J. & Lynne deBenedette (2011). Processing instruction and Russian: Further evidence is in. Foreign Language Annals, 44(4), 646-673. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01155.x

Dabiri, Asma (2018). Comparing two modes of instruction in English passive structures (processing and meaning-based output instruction). JEES (Journal of English Educators Society), 3(1), 67-84. https://doi.org/10.21070/jees.v3i1.1259

De Costa, Peter I. et al. (2022). Bridging the researcher–practitioner divide through community-engaged action research: A collaborative autoethnographic exploration. The Modern Language Journal. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12796

DeKeyser, Robert (2015). Skill acquisition theory. In Bill VanPatten & Jessica Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 94-112). New York, NY: Routledge.

Dyson, Bronwen (2018). Developmental sequences. In John I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1-8). John Wiley & Sons.

Dyson, Bronwen Patricia & Gisela Håkansson (2017). Understanding second language processing: A focus on processability theory (Vol. 4). John Benjamins.

Ellis, Rod (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19(3), 221-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x

Fahim, Mansoor & Hessameddin Ghanbar (2014). Processing instruction and dictogloss: Researching differential effects of two modes of instruction on learners’ acquisition of causatives. Journal of Education & Practice, 5(37), 204-214.

Fakharzadeh, Mehrnoosh & Manidjeh Youhanaee (2012). The effect of an output-packet practice tasks on the proceduralization of knowledge in intermediate Iranian foreign language learners. The 1st Conference on Language Learning & Teaching: An Interdisciplinary Approach (LLT-IA), 1-24. University of Isfahan, Iran.

Fakharzadeh, Mehrnoosh & Manidjeh Youhanaee (2015). Proceduralization and transfer of linguistics knowledge as a result of form-focused output and input practice. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 18(1), 65-94. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-2491-fa.html

Farahian, Majid & Farnaz Avarzamani (2019). Processing instruction revisited: Does it lead to superior performance in interpretation and production?. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 89-111. https://doi.org/10.32601/ejal.543783

Gholami, Javad & Maryam Zeinolabedini (2018). Learnability and teachability hypothesis. In John I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1–7). Hoboken: Wiley.

Gholami, Nawal & Farvardin, Mohammad Taghi (2017). Effects of input-based and output-based instructions on Iranian EFL learners’ productive knowledge of collocations. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 6(3), 123-130. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.6n.3p.123

Grammar and Resources: Present perfect. (2007). Persian Online. University of Texas, Austin. Retrieved March 31, 2024, from https://sites.la.utexas.edu/persian_online_resources/

Hwang, Hee-Jeong (2018). A study on the Korean EFL learners' grammatical knowledge development under input-enhanced FFI and output-enhanced FFI conditions. Journal of Digital Convergence, 16(5), 435-443. https://doi.org/10.14400/JDC.2018.16.5.435

Izumi, Shinichi (2002). Output, input enhancement, and the noticing hypothesis: An experimental study on ESL relativization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24(4), 541-577. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263102004023

Izumi, Shinichi & Martha Bigelow (2000). Does output promote noticing and second language acquisition?. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 239-278. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587952

Izumi, Yukiko & Shinichi (2004). Investigating the effects of oral output on the learning of relative clauses in English: Issues in the psycholinguistic requirements for effective output tasks. Canadian Modern Language Review, 60(5), 587-609. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.60.5.587

Jeong, Hyojin & Haemoon Lee (2018). The effects of two types of written output tasks on noticing and learning of vocabulary. Korean Journal of Applied Linguistics, 34(4), 75-102. https://doi.org/10.17154/kjal.2018.12.34.4.75

Jourdenais, Renée et al. (1995). Does textual enhancement promote noticing? A think-aloud protocol analysis. In Richard Schmidt (Ed.), Attention and awareness in foreign language learning (technical report #9) (pp. 183-216). University of Hawai’i, Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center.

Kang, Dongho (2011). Noticing and L2 learning in input-based focus-on-form instruction. Foreign Languages Education, 18(2), 29-49. UCI: G704-000287.2011.18.2.017

Kang, Dongho (2003). Focus on form instructions and L2 learners’ instructional preferences. Foreign Languages Education, 10(1), 57-82. UCI: G704-000287.2003.10.1.007

Kang, Nayeon (2009). Effects of form-focused instructions on the learning of English verb complementation by Korean EFL learners. English Teaching, 64(1), 3-25. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.64.1.200903.3

Khani, Fahimeh & Mehran Davaribina (2013). The relative effects of processing instruction and meaning-based output instruction on acquisition of English conditional sentences. The Iranian EFL Journal, 9, 311.

Kim, Boram (2002). The role of focus on form in the EFL classroom setting: Looking into recast and CR tasks. English Teaching, 57(4), 267-296. UCI: G704-000189.2002.57.4.022

Kim, Jeong-eun (2014). Timing of form-focused instruction and development of implicit vs. explicit knowledge. English Teaching, 69(2), 123-147.

Kim, Jeong-eun & Hosung Nam (2017). The pedagogical relevance of processing instruction in second language idiom acquisition. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 55(2), 93-132. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2015-0027

Lee, Haemoon (2003). The effects of production and comprehension for focus on form and second language acquisition. Korean Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19(2), 41-68. UCI: G704-000491.2003.19.2.010

Lee, Haemoon (2002). Communicative output as a mode of focus on form. English Teaching, 57(3), 171-192. UCI: G704-000189.2002.57.3.006

Lee, Hikyoung (1999). Variable article use in Korean learners of English. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, 6(2), 35-47. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss2/4

Lee, Icy (2019). Teacher written corrective feedback: Less is more. Language Teaching, 52(4), 524-536. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444819000247

Lee, Sang-Ki (2007). Effects of textual enhancement and topic familiarity on Korean EFL students' reading comprehension and learning of passive form. Language Learning, 57(1), 87-118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00400.x

Lee, Sang-Ki & Hung-Tzu Huang (2008). Visual input enhancement and grammar learning: A meta-analytic review. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30(3), 307-331. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263108080479

Leow, Ronald. P. et al. (2003). The roles of textual enhancement and type of linguistic item in adult L2 learners' comprehension and intake. Applied Language Learning, 13(2), 1-16.

Lim, Jayeon (2007). Input enhancement in the EFL learning of present perfect and the lexical aspect. Modern English Education, 8(3), 38-60. UCI: G704-001860.2007.8.3.005

Long, Michael & Peter Robinson (1998) Focus on form: theory, research, and practice. In Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 15-41). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Luk, Zoe Pei-sui & Shirai, Yasuhiro (2009). Is the acquisition order of grammatical morphemes impervious to L1 knowledge? Evidence from the acquisition of plural ‐s, articles, and possessive ’s. Language Learning, 59(4), 721-754. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2009.00524.x

Maleki, Ataollah (2006). The impact of the head-initial/head-final parameter on reading English as a foreign language: A hindering or a facilitating factor?, The Reading Matrix, 6, 154-169.

Mazdeh, Mohsen Mahdavi (2013). Future. Persiandee.com. http://www.persiandee.com

Modirkhamene, Sima et al. (2018). Processing instruction: Learning complex grammar and writing accuracy through structured input activities. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 177-188. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v8i1.11479

Momenzade, Marjan & Manijeh Youhanaee (2014). ‘Number’ and article choice: The case of Persian learners of English. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 1186-1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.533

Moradi, Mehdi & Mohammad Taghi Farvardin (2016). A comparative study of effects of input-based, meaning-based output, and traditional instructions on EFL learners’ grammar learning. Research in Applied Linguistics, 7(2), 99-119. https://doi.org/10.22055/RALS.2016.12096

Naseri, Elahe & Farzaneh Khodabandeh (2019). Comparing the impact of audio-visual input enhancement on collocation learning in traditional and mobile learning contexts. Applied Research on English Language, 8(3), 383-422. https://doi.org/10.22108/are.2019.115716.1434

Nassaji, Hossein & Sandra S. Fotos (2011). Teaching grammar in second language classrooms: Integrating form-focused instruction in communicative context. New York, NY: Routledge.

Persian in context: Grammar book to accompany units 1-8. (2013). Raleigh, NC: North Carolina State University. https://cdn.chass.ncsu.edu/sites/fll.chass.ncsu.edu/persian/persian_in_context/Compiled grammar.pdf

Pienemann, Manfred (2005). Cross-linguistic aspects of Processability Theory (Vol. 30). John Benjamins Publishing.

Pienemann, Manfred & Anke Lenzing (2015). Processability Theory (2nd ed.). In Bill VanPatten & Jessica Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp.159-179). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203628942

Rahemi, Jamileh (2018). The effect of isolated vs. combined processing instruction and output-based instruction on the learning of English passives. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 163-194. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-2939-fa.html

Rassaei, Ehsan (2012). The effects of input-based and output-based instruction on L2 development. TESL-EJ, 16(3). Retrieved from https://tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume16/ej63/ej63a2/

Rassaei, Ehsan (2015). Effects of textual enhancement and input enrichment on L2 development. TESOL Journal, 6(2), 281-301.

Rice, Marnie E. & Grant T. Harris (2005). Comparing effect sizes in follow-up studies: ROC Area, Cohen's d, and r. Law and Human Behavior, 29(5), 615-620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-6832-7

Sadeghi Beniss, Aram Reza, & Vahid Edalati Bazzaz (2014). The impact of pushed output on accuracy and fluency of Iranian EFL learners’ speaking. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 2(2), 51-72.

Sarkhosh, Mehdi et al. (2013). Differential effect of different textual enhancement formats on intake. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 544- 559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.092

Shin, Mi-kyung (2011). Effects of output tasks on Korean EFL learners’ noticing and learning of English grammar. Foreign Language Education, 18(2), 127-163. UCI: G704-000287.2011.18.2.014

Shin, Mi-kyung (2015). The resetting of the head direction parameter. Studies in Foreign Language Education, 18, 17-35. http://hdl.handle.net/10371/95840

Shintani, Natsuko (2011). A comparative study of the effects of input-based and production-based instruction on vocabulary acquisition by young EFL learners. Language Teaching Research, 15(2), 137-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810388692

Song, Mi-Jeong (2007). Getting learners’ attention: Typographical input enhancement, output, and their combined effects. English Teaching, 62(2), 193-215. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.62.2.200706.193

Song, Mi-Jeong & Bo-Ram Suh (2008). The effects of output task types on noticing and learning of the English past counterfactual conditional. System, 36(2), 295-312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.09.006

Soruç, Adem (2018). The mediating role of explicit information in processing instruction and production-based instruction on second language morphological development. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 18(3), 279-302. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/buje/issue/55539/760450

Spada, Nina & Tomita, Yasuyo (2010). Interactions between type of instruction and type of language feature: A meta‐analysis. Language Learning, 60(2), 263-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00562.x

Sullivan, Gail M., & Richard Feinn (2012). Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4(3), 279-282. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1

Swain, Merrill (1998). Focus on form through conscious reflection. In Catherine Doughty and Jessica Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in classroom second language acquisition (pp. 64-81). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Uludag, Onur & Bill VanPatten (2012). The comparative effects of processing instruction and dictogloss on the acquisition of the English passive by speakers of Turkish. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 50(3), 189-212. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2012-0008

VanPatten, Bill (2004). Processing instruction: Theory, research, and commentary. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

VanPatten, Bill (2014). On the limits of instruction: 40 years after 'Interlanguage'. In Zhao-Hong. Han & Elaine Tarone (Eds.), Interlanguage: 40 years later (pp. 105-126). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Wang, Ting & Lin Jiang (2015). The effects of written corrective feedback on Chinese EFL learners’ acquisition of English collocations. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 38(3), 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2015-0020

Yang, Miran (2004). A comparison of the efficacy between input-based instruction and output-based instruction in focus on form. English Teaching, 59(2), 145-164. UCI: G704-000189.2004.59.2.012

Yang, Miran (2008). The effects of task difficulty on learners’ attention to meaning and form during focus-on-form instruction. Foreign Languages Education, 15(3), 27-52. UCI: G704-000287.2008.15.3.006

Yang, Man et al. (2017). An investigation of cross-linguistic transfer between Chinese and English: a meta-analysis. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education, 2(15), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-017-0036-9

Yeo, Kyunghee (2002). The effects of dictogloss: A technique of focus on form. English Teaching, 57(1), 149-167. UCI: G704-000189.2002.57.1.011

Younesi, Hossein & Zia Tajeddin (2014). Effects of structured input and meaningful output on EFL learners' acquisition of nominal clauses. Iranian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 17(2), 145-167. http://ijal.khu.ac.ir/article-1-2250-fa.html.

Author:

Andrew Schenck

Assistant Professor

Department of English

Fort Hays State University, Kansas

Email: adschenck@fhsu.edu