Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching

10th Anniversary Issue (2020), pp. 29-51

Just because Constructions in Spoken and Written

New Zealand English

Andreea Calude (Hamilton, New Zealand) & Gerald Delahunty (Fort Collins, CO, USA)

Abstract

Just because (JB) is widely used and has been a target of commentary and humorous use by English speakers and aroused some interest among linguists, who have investigated its syntax, semantics, and derivation. Some, based on researcher constructed data, have proposed construction analyses (Hirose 1991, Bender and Kathol 2001). Another (Hilpert 2005: 97), using a diachronic corpus, proposes that JB has been grammaticalized as a concessive marker via "the discourse function of inference denial." Our study, based on a corpus of New Zealand written and spoken English, demonstrates, amongst other significant findings, that JB occurs in a far broader set of grammatical contexts than the earlier literature recognizes, that JB constructions are significantly more frequent in spoken than in written English, that JB adverbial clauses are more likely to occur in pre-posed than in post-posed position, that the meaning of just because affects this distribution, that just because is far more likely to be followed by a clause than a prepositional phrase, and that JB constructions are extremely likely to occur in the discourse context of a negator.

Key words: Just because, inference denial, New Zealand English, polarity, spoken language, quantitative linguistics

1 Introduction

The expression just because (JB),(1)(2) is strongly enregistered (e.g. Agha 2003, Silverstein 2003, Johnstone 2014). It occurs across multiple genres and media and as a target of popular usage commentary (e.g. https://www.quickanddirtytips.com/education/ grammar/ can-you-start-a-sentence-with-just-because), commercial (e.g. just because e-cards; just because flower shops), and humorous use (e.g. Homer Simpson cartoons https://me.me/i/just-because-i-dont-care-doesnt-mean-i-dont-understand-11750940; Japanese anime film http://justbecause.jp/). An internet search on Google Chrome for just because returned "About 7,090,000,000 results (0.56 seconds)" (29-11-2019)(3).

In spite of its ubiquity and prominence, it has garnered little interest from linguists. Those who have addressed it investigated its syntax, semantics, and derivation. However, these studies are limited by their decontextualized data and their narrow foci, e.g. on the construction in which JB introduces a finite clause functioning as the subject of a predicate headed by doesn't mean (1), and its relation to a construction in which an adverbial clause introduced by JB is pre-posed to a sentence whose it-subject is anaphoric to the JB construction and whose predicate is also headed by doesn't mean (2).

(1) Just because he's a bloke doesn't mean that he's wrong (#28). (4)

(2) Just because he's a bloke, it doesn't mean he's wrong.

Because of its remarkable online presence and our belief that just because and the structures incorporating it are in flux - just because may be grammaticalizing, perhaps lexicalizing, though our methodology does not allow us to determine this, and the structures it introduces may be expanding their syntactic range - our study is the first in a series of proposed comparisons of JB constructions across various English dialects. Because one of us (Calude) is thoroughly familiar with the New Zealand Corpus of Written and Spoken English (Holmes et al. 1998, Bauer 1993, Calude & James 2011), this paper presents a corpus-based study of the forms, meanings, and functions of JB constructions(5) in New Zealand English (NZE).

2 Goals of this Study

In contrast to the narrow theoretical foci and limited data sources of earlier studies of JB, we have two interacting goals for this study. First, we identify the formal, semantic, and discourse features of the JB constructions, specifically:

i. the relative frequency of each construction in spoken and written mode,

ii. the range and relative frequencies of constructions introduced by JB and their grammatical roles,

iii. the interaction between the meanings of a JB construction and its grammatical distribution, and

iv. the polarity characteristics of the JB constructions and of the discourse contexts in which the constructions occur.

Second, we explore co-occurrence relationships amongst these features, e.g. the semantic and pragmatic features associated with JB constructions functioning as sentential subjects.

3 Brief Literature Review

With one exception (Hilpert 2005, 2007), the prior research on just because is based on data constructed by authors in support of particular theoretical analyses - construction grammar (Hirose 1991, Bender & Kathol 2001, Kanetani n.d, 2007, 2019), and minimalism (Matsuyama 2001). Hilpert argues from a diachronic corpus that JB has grammaticalized into a concessive marker indicating inference denial. While our study has substantially different goals and methodology, we nonetheless feel genre-bound to review that research, however briefly. We discuss the most important of our precursors in chronological order.

3.1 Hirose (1991)

Hirose (1991) provides an intricate argument that (just) because-clauses in subject position derive "from the blending of a construction with a that-clause as subject and one with an adverbial because-clause" when "they perform an identical function," in this case "to deny the inferential process of drawing a certain conclusion from a certain factual premise and express some doubt about the validity of the conclusion as well." This "semantic function" "restricts the distribution of because-clause subjects" to "negative sentences with verbs of inference" (32).

However, Hirose's analysis is unsatisfactory in several ways. First, it does not specify exactly how the blending of the two constructions is effected. Second, it is observationally inaccurate in several respects: (i) His claim that the main clause of a sentence with a because-clause subject must be headed by a verb of inference (18) must be revised to allow other expressions of inference such as nouns like reason, as attested by his example: Because men are still incapable of being angels is no good reason why they should be ants. (ii) His claim to the contrary notwithstanding (19), because-clause subjects do occur in positive sentences, e.g. Because some body parts have already been turned into commodities means that trade in human organs must be better regulated [adapted from Huddleston & Pullum (2002: 731, [24] i)]. Third, he regards just as an optional modifier of because (17), and so fails to distinguish the two expressions: just because is a strongly entrenched and enregistered expression and occurs far more frequently as the introducer of a subject clause than because does. A search for because in the spoken COCA corpus returned no because-clause subjects in the first 100 concordance lines, whereas a search for just because returned 14 just because-clause subjects. Fourth, his claim that the inference denial interpretation of a because-clause subject is a "semantic function" (32, emphasis added) contradicts his claim that the inferential reading is based on Piercean abduction (20) for the simple reason that the abductive process is a pragmatic one (though he may be using "semantic" more broadly than he should). We believe that this analysis is unwarranted because the semantics of the predicate of the main clause - mean / reason - denotes the inferential relationship. Additionally, Hirose claims that the abductive process cannot return a causal reading of because-clause subject constructions, though he does not explain why.

3.2 Bender & Kathol (2001)

Bender & Kathol (2001) [B&K] argue for a construction analysis of inference, denying just because sentences, e.g. Just because we live in Berkeley doesn't mean that we're left wing radicals (B&K example 1). They argue that the just because expression and the predicate are not combined into a single sentence as subject and predicate by English syntax. Rather, they are combined as a "specialized subtype of head-modifier constructions" in which the just because construction is always an adjunct (18) that "preced[es] a negated main clause, and specifies that the negation in the main clause should take scope over the adjunct" (15). This allows for the inference denial reading, which would be impossible if the JB construction were the syntactic subject, as the negator could not take the JB construction within its scope.

However, the JB constructions pass several of the tests for subjecthood identified in Huddleston & Pullum (2002: 236-243). They occur immediately before their predicates. The sentence may undergo subject auxiliary inversion, e.g. Doesn't just because he's rich mean he's happy? Does just because he's rich not mean he's happy? And tag questioning, e.g. Just because he's rich doesn't mean he's happy, does it? A single overt subject allows for coordinated predicate VPs, e.g. Just because the T.V. is on doesn't mean we're watching it or care about it. Subjects are typically obligatory in indicative sentences, so an inference denial sentence in which the JB construction is juxtaposed to its predicate but is not a subject, violates this general pattern. Matsuyama (2001) provides several further arguments for the subjecthood of JB constructions. All of these observations strongly suggest that the JB construction can be a subject and should therefore be outside the scope of the negation. However, the following remarks on the scope of negation from Horn & Wansing (2017) suggest that the case may be more complicated than Bender & Kathol assume.

Negation also interacts in complicated and often surprising ways with quantification and modality. Perhaps the most analyzed interaction is with universal quantification. Despite the locus classicus 'All that glitters is not gold' and similar examples in French, German, and other languages, the wide scope of negation over universal subjects (or in cases like All the boys didn’t leave, the possibility of such readings, depending on the speaker, the intonation contour, and the context of utterance) is often condemned by purists, yet is not as illogical as it may appear.

3.3 Matsuyama (2001)

Matsuyama (2001) presents a minimalist (Chomsky 1995) analysis of both clausal and phrasal JB constructions, respectively: Just because he is a professor of medicine at Cambridge does not make his findings unquestionable [Matsuyama's (4b)] and Just because of his dumb mistake doesn't mean you're going to have lights out in Manhattan (Kanetani 2019: 131 (1). He argues thoroughly and convincingly that clausal JB constructions can be sentential subjects (332-351). He also argues that within his minimalist analysis, just because of NP is a prepositional phrase and consequently cannot function as a subject (351-352), and thus accounting for the ungrammaticality he accords *Just because of my being here doesn't mean I didn't go [his (67) adapted]. We will have more to say about this judgment in our discussion of Kanetani (2019).

3.4 Hilpert (2005)

Hilpert (2005) is a diachronic corpus study of the "grammaticalization of the English phrase just because into a concessive marker" (85) "by way of the discourse function of inference denial." His data consist of 2062 instances of just because drawn from several corpora: BNC written, Literature Online, Modern English Text Collection, and London Times Digital. He argues that the phrase just because has grammaticalized into a concessive marker (85), though he provides no proof of grammaticalization or of concessivity. He argues that "[s]entences of the form just because X it doesn't mean Y state that Y is not a valid inference from the fact X" (87). Hilpert identifies a range of expressions, verbal, nominal, and idiomatic, that "are semantically related to inferencing" and that function in the place of doesn't mean in the JB sentences, e.g. assume, think (88, his Table 3). Hilpert also provides a list of 13 "syntactic environments" in which JB occurs in his data (90-91, his Table 4) which we present in our Table 4 below along with the types of JB constructions identified in our data but not in Hilpert's. He briefly discusses each of his environments, paying special attention to the constructions represented by Just because X, it doesn't mean Y and Just because X doesn't mean Y, both of which "appear only after 1950" (94) and "instantiate the semantic prototype of inference denial," though the form without the it main-clause subject now occurs more frequently than its alternative (91).

3.5 Hilpert (2007)

Hilpert (2007) is a less technical follow-up to Hilpert (2005). It repeats the analysis of JB constructions proposed there and wonders why the JB clausal construction has not excited any prescriptive animus even though it is a recent and somewhat idiosyncratic innovation not entirely consistent with English grammar. He argues that it escaped critical scrutiny because it "gradually evolved out of a canonical syntactic structure," which he characterizes as "a regular hypotactic (subordinate) construction - a preposed because clause followed by a negative main clause" (32), from which it developed into an idiomatic marker of concessivity (31). It certainly has not escaped scrutiny now, as our Google searches indicate.

3.6 Kanetani (n.d., 2007, 2019)

Kanetani discusses the JB and related constructions in a series of papers (n.d., 2007, and 2019), although he does not distinguish sentences in which the subordinate clause is introduced by because from those introduced by just because. Kanetani (n.d.) argues that JB constructions of the types represented in (1) and (2) above are similar to "reasoning" constructions such as It has rained, because the ground is wet because the because-clause represents a premise from which the proposition represented by the main clause can be inferred. They are similar to "causal" constructions such as The ground is wet because it has rained as the because-clause is presupposed in each type.

Kanetani (2007) compares patterns of modification of because and since by "focalizing" adverbs such as simply, only, and just. Drawing on Quirk et al. (1985) he distinguishes between exclusive and particularizing focalizing adverbs (e.g. just, simply, etc. vs. especially, largely, etc.; 353), he concludes that conjunctions in the causal construction can be focalized by both exclusives and particularizers, e.g. He went to college just / largely because his parents asked him to [cf. Kanetani's (30) and (31)], whereas inferential because and since clauses can be focalized by particularizers but not by exclusives (357). While analysis of the distribution of these adverbs would benefit from a corpus study, this is beyond the purview of our present study.

Kanetani (2019: 131-145) engages Matsuyama's (2001) minimalist explanation for the ungrammaticality of sentences of the form Just because of NP doesn't mean Y - the JBoDM construction. Kanetani notes that such sentences do occur (none occur in our corpus) even though they are felt to be less than fully grammatical. He provides a construction grammar analysis derived from that in Hirose (1991) that accounts for both their occurrence and residual feeling of ungrammaticality: the JBoDM construction is produced online by analogy with the inference denying because construction; the latter is "well entrenched," the former "is a product of analogical deduction" and is therefore not an established construction (145).

4 Methods, Data, and Coding

The data for our analysis is drawn from corpora of spoken (approx. 1 million words) and written (approx. 6 million words) of New Zealand English. Our AntConc (Anthony 2016) search for the string just because returned 90 useable instances of the expression and surrounding context (we included 2-3 sentences or turns before and after the constructions).

As we discussed in Section 3, previous accounts of JB constructions have uncovered some of their different syntactic forms and their combinations, as well as their distinct pragmatic interpretations and characteristics. One of the major goals of our work here is to unite the (fuller) range of these two different sets of characteristics in the same analysis in order to study how these might pattern together (that is, which syntactic forms might be associated with which semantic, pragmatic, and discourse characteristics). To this end, we manually coded our 90 examples for a number of variables, as described and exemplified below. We especially want to emphasize our use of naturally occurring data (rather than introspective, author-created examples as has been done in the majority of previous work on JB constructions), because we believe that naturally occurring data contains the key to identifying and understanding the full range of uses and functions of the construction by speakers.

First, we coded the linguistic medium - spoken or written discourse - that the JB construction occurred in. To the best of our knowledge, no one has considered this distinction in relation to JB constructions before.

Second, we considered syntactic form. Table 1 lists the types of complements of JB that we encountered in our data, though we also found instances from other sources in which just because seems to reject a complement:

(3) "Oh, oh, why?" pleaded the girls.

"Because."

"Because what?"

"Just because." (Farrell 2002: 300)

| JB Construction | Example |

1 | just because + prepositional phrase | just because of an accident or what (#71) |

2 | just because + simplex clause | just because they called him a director doesn't mean that he was necessarily a partner (#68) |

3 | just because + complex clause | just because the international bankers say you've got to do this (#73) |

4 | just because + coordinated clauses | just because someone else breaks a window and steals something (#70) |

Table 1: Structural Types of JB Constructions

Third, we identified the grammatical functions of the JB constructions we discovered in our data, which we list with examples in Table 2:

| Functions of the JB Construction | Example |

1 | Subject | Just because they called him a director doesn't mean that he was necessarily a partner (#68) |

2 | Preposed adverbial clause | Just because our population is small, it doesn't mean that we are less deserving . . . (#30) |

3 | Post-posed adverbial clause | "You can tour just because you want to tour and make it an event . . ." (#6) |

4 | Complement clause | We are told it is just because Elm Court is not making a profit. (#13) |

5 | Stand-alone (not grammatically integrated into a larger unit) | Speaker 1: yeah it sounds gripping news all right Speaker 2: oh yes just because you won't eat them (#79) "You ask very obscure questions, Mr Craddock," complained Mr Tyler. "Just because you contemplate the answer in advance and you don't like the answer, Mr Tyler. Is that not the position?" asked Mr Craddock. (#24) |

Table 2: Grammatical Functions of the JB Construction

Fourth, we determined for each JB sentence, whether the JB construction could be moved from the position it occupied in the original to another position in the sentence. For example, we determined whether preposed JB constructions might be post-posed. Compare the preposed JB construction of (5) with the post-posed version in (6).

(5) Just because it's not now on the agenda, and most are supportive and comfortable with our present system, there's no reason not to provide for a process to manage the inevitable debate (#22).

(6) There's no reason not to provide for a process to manage the inevitable debate, just because it's not now on the agenda, and most are supportive and comfortable with our present system.

Conversely, some post-posed JB constructions may be preposed:

(7) I would probably continue to do this even if the business made only a modest profit on some jobs and even losses on others, just because I am passionate about it (#33).

(8) Just because I am passionate about it, I would probably continue to do this even if the business made only a modest profit on some jobs and even losses on others.

Not all our examples allow these reversals, so our fourth factor is a binary distinction regarding the possibility of reversal.

Fifth, we noted whether the JB expression was associated with a negator and if so, where the negator might occur. We found several possibilities:

Examples where the negator modified the JB expression itself:

(9) McCaw and Carter will be valued not just because they are once in a life-time players but because they offer a lot in terms of leadership . . . (#8)

Examples where the negator was inside the JB construction include:

(10) We are told it is just because Elm Court is not making a profit (#13)

Examples where the negator modifies the verb mean:

(11) Just because our population is small, it doesn't mean that we are less deserving . . . (#30).

Examples where the negator negates the main clause with which the JB construction was associated:

(12) Sacremento's lawyer Robert Fardell, QC, said the authority was not sued just because it was thought to have 'deep pockets' . . . (#29).

Sixth, we noted the number of negators within the JB construction and in its relevant context, which we characterize as the intensity of negation of the fragment of discourse.

Seventh, we noted whether the JB construction was presupposed or not. We deemed it to be presupposed if both of us agreed that it was not asserted and if it seemed to be assumed to be true whether positive, negated or questioned, i.e. whether it "survived negation" and interrogation. Of the 90 instances, 80 (88.9%) were presupposed:

(13) there's nothing to stop you going this other way just because everyone goes to england (sic) the <laughs> the same old way (#89).

Four instances (4.4%) were not presupposed, e.g.:

(14) was that just because of an accident or what (#71)

And six instances (6.7%) were undecidable, e.g.:

(15) Speaker A: yeah it sounds gripping news all right

Speaker B: oh yes just because you won't eat them (#79)

Finally, we identified several meanings associated with JB constructions. Table 3 specifies these, giving examples of each type(6):

| Meanings | Example |

1 | for this reason alone (RA)(7), in other words, for this reason and only / just this reason | But the jury had to be certain that Watson had lied and not just been mistaken. People had many different reasons for lying -- the jury must not decide that just because a person lied he or she was guilty. However, lies could be a guide to the general credibility of a person. (#5) |

2 | for this reason and others (RO), in other words, this is just one reason among other reasons | 'A lovely try,' making me blush, but I see other men smiling and nodding their heads, and understand he's speaking for them all, and I move closer to him on the seat. He's pleased not just because our team has won. It's the beauty of the cut-through that moves him, and the pass from centre to wing, and the run for the corner. (#60) |

3 | for no better reason than (NBR), in other words, for this reason which is not even a good reason | He seems to think, just because his head is full of Jesus, that he has a direct telephone line with him. Well, boy, let me tell you a thing or two about Sione. (#58) |

Table 3: Semantic Interpretations of JB Constructions

4.1 "Syntactic Environments" of just because

Hilpert (2005: 89-94) provides a valuable list of 13 "syntactic environments of just because" and their typical meanings. Our NZE corpora included 12 other environments not found by Hilpert in his British and American data. We append our 12 environments to Hilpert's 13 in Table 4. The table gives the structure of the environment, an example of each structure, the meaning of the JB construction, and the frequency of each type in our corpora.

Structure | Hilpert's examples | Meaning | Frequency in NZE Corpus |

1. Just because X it doesn’t mean Y. | Just because you play guitars it doesn’t mean you’ve got soul. | Inference denial | 4 |

2. Just because X doesn’t mean Y. | Just because data satisfy expectations doesn’t mean they are correct. | Inference denial | 17 |

3. Just because X NEG-CLAUSE. | Just because you donate an egg, that does not make you a parent.

| Inference denial and concessive

| 4

|

4. Just because X NEG-VP. | Just because it’s a Number One record doesn’t make it a better record.

| None given | none |

5. Just because X POS-CLAUSE. | “Just because he won a few stupid car races,” she went on, “he seems to think he rules the world.” | Not normally concessive, cause not well founded. | 3 |

6. Just because X POS-VP. | Just because he’s got a black belt means nothing. | VP has negative meaning, though formally positive | none |

7. Just because X! | Just because she’s never had a proper job. | Exclamatives with causal and concessive meanings | 1 |

8. NEG-CLAUSE just because X. | You cannot leave your parents just because you want to. | Concessive and causal | 24

|

9. POS-CLAUSE just because X. | Utopias lead to disappointment just because they are utopias. | Causal | 16 |

10. POS-CLAUSE not just because X. | “We had a very good season,” Walsh reflects, “not just because we’ve won something, but because you learn in the process.”

| JB construction in scope of NEG so downplay validity of invoked reason | 4

|

11. POS-CLAUSE just because of X. | A total of 37 in every 100 women believe that bankers treat them differently just because of their sex. | Causal | 2

|

12. POS-CLAUSE not just because of X. | Clients were also causing headaches, and not just because of fees. | Denies causal relationship | 1 |

13. NP is just; because CLAUSE | The Lords of Earth presume to think Their Actions just, because we please to wink. | just means “fair” – pre-grammaticalized meaning | none (our search did not allow it) |

Examples found in the NZE corpora but not found by Hilpert (2005) | |||

a. And not JB construction | And not just because it was Picasso who had so few redeeming features. (#1) | For this reason and others; presupposed JB construction | 2 |

b. NEG-CLAUSE just because of NP | The subject of his first great musical partnership hasn't come up just because of that anniversary.(#2) | Cause, for no other reason than … | 2 |

c. JB construction. Tag question | Just because you contemplate the answer in advance and you don't like the answer, Mr Tyler. Is that not the position? (#24) | Undecidable | 1 |

d. X NEG-think that JB construction, clause | Clearly Mendoza doesn't think that just because you know about cars, you have to give up the more feminine joys in life. (#26) | Denies that presupposed JB construction is adequate reason for clause | 1 |

e. or JB construction | His determined struggle into the Otago University staff club for the front-bench meeting, after a nasty cycling accident was a sign of his determination to support Phil Goff- or just because Mr Mallard never resists a chance to air his views? (#31) | Potential alternative reason for action | 1 |

f. JB of X, POS-Clause | Just because of the earthquake, I was wondering whether people would want to come into town, but it was like everybody needed a bit of a laugh. (#47) | Reason | 1 |

g. If clause, JB construction, then clause | If her mind gets all disturbed and upset just because she sees wiki then it's pathetic. (#57) | Reason/cause | 1 |

h. Wh-clause JB construction | What makes a lie more respectable just because it is said by an MP? (#64) | Reason/cause | 1 |

i. Stand alone JB sentence | um i guess it's we've just been taking things more seriously and that and just <new speaker> what things <first speaker> just because small group for a long time was just more of a social time together rather than talking about anything christian or as a support group or anything you know as any real function like that it was just like a get together and muck around and smoke cigars and do stupid things and that's all we did. (#69) | Reason/cause | 1 |

j. NEG clause JB construction | I haven't been living on a diet of takeaways just because I've had twelve pies in the last three days it's only because the garage was close to the film festival. (#40) | Inferential | 1 |

k. why JB construction | why just because you were away from home? (#84) | Reason/cause | 1 |

l. NEG JB construction as focus of it-cleft | When Prime Minister Jim Bolger lost his temper with Winston Peters in Parliament last week . . . it was not just because he sees sly racism in the NZ First leader's anti-immigration campaign. (#87) | Reason/cause | 1 |

Table 4: Types of JB Constructions from Hilpert (2005: 89-94) and NZE Fata

So, even though our database consists of just 90 examples, it includes a much broader range of distinguishable sub-types than Hilpert's much larger dataset and represents a broader range of meanings of just because. We do not know whether these uses are unique to New Zealand English or whether they are attributable to the careful manual inspection of our examples; future work would clarify this.

5 Statistical Analyses

As outlined in our methods section, our data consisted of three types of categorical variables: seven different syntactic / grammatical variables (such as function or position of the JB construction), two discourse-pragmatic variables (linguistic mode; whether or not the JB construction is presupposed), and one semantic variable (the interpretation of the JB construction). There was one exception, namely, the variable of JB construction length is numerical, which we coded as total number of words. We wanted to explore potential associations between the form of the JB construction and its interpretation, or use in discourse, and following this, any interactions between these. We discuss the simple associations first and consider interactions thereafter.

It is not straight-forward to analyse association measures between so many categorical variables, especially given the small data sample available to us. For these reasons, hypothesis testing was not possible. Instead, we used Cramer’s V value as a measure of association (as suggested by Levshina 2015: 222), and we performed Fisher’s exact tests in addition (some of our counts were zero so Fisher’s exact was more appropriate than a traditional Chi Square test(8)). Our primary interest was any potential association between interpretation and form, so we calculated the values above for all the combinations between the interpretation variable and all other variables coded. The results are given in Table 5 (the most significant ones are shaded).

Variables | Cramer’s V(9) | Fisher’s(10) exact (2-sided) | Strength of Association |

Interpretation & Function | 0.20 | 0.422 | low-moderate |

Interpretation & Position | 0.253 | 0.056* | moderate |

Interpretation & Structure | 0.27 | 0.051* | moderate |

Interpretation & Mode | 0.42 | 0.0001*** | high |

Interpretation & Presupposition | 0.16 | 0.056 | low |

Interpretation & Reversibility | 0.48 | <0.001*** | high |

Interpretation & negation locus | 0.21 | 0.099 | low-moderate |

Interpretation & negation intensity | 0.198 | 0.369 | low |

Table 5: Association Measures between Interpretation of JB Constructions and Various Formal and Discourse-Pragmatic Factors

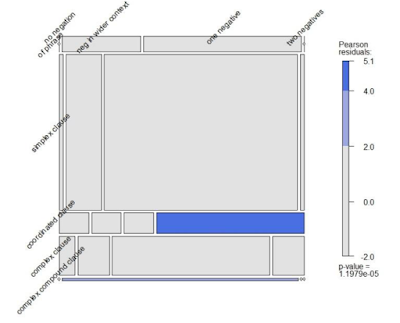

The strongest association was observed between the JB construction interpretation and its reversibility, position and structure, and the linguistic mode it occurred in. One useful way of visualising these associations is via Mosaic plots (Baayen 2008: 111-113, Levshina 2015: 219). Figures 1-7 below give the Mosaic plots corresponding to these relationships. We discuss each one in turn.

First, we consider the spread of JB constructions across the two modes investigated: speech and writing. Given the total number of words examined in the two modes, speech has significantly more occurrences of JB constructions compared to writing (Fisher’s Exact p<0.001, CI (5.678, 13.882), odds ratio=8.83) even when ignoring the JB constructions used in quotes in the written corpus (Fisher’s Exact p<0.001, CI (2.974, 8.348), odds ratio=5.00).

However, when looking at the actual JB constructions in our data, we found further differences between how they are used across speech and writing, depending on their more specific interpretation. The Mosiac plot in Figure 1 gives the relative proportion of JB constructions of various meanings (across columns, from left to right) as found in the different modes (across rows, from top to bottom). The plot shows that the greatest proportion of our data was made up by the JB constructions interpreted as “no better reason” and found in spoken language (the largest grey box in the plot):

Figure 1: Mosaic Plot of JB Construction Interpretation and Mode

The Mosaic plot also shows that JB constructions whose meaning can be summarized by “this and other reasons” are significantly more likely to be found in written than in spoken language (where they are altogether absent). The blue box indicates a statistically significantly higher than expected proportion of JB constructions meaning “this and other reasons” in written language, and the tiny red box indicates significantly fewer than expected counts of JB constructions meaning “this and other reasons” in speech (note that mosaic plots automatically calculate a Chi-Square p-value; we prefer the more conservative Fisher Exact test – they both give the same answer in this case).

We now turn to associations found between the various interpretations of JB constructions and their formal properties. The first association plot we consider is between JB construction interpretation and likelihood of being able to reverse the order of the JB construction and the y-clause.

In Figure 2, we see that JB constructions meaning “this and other reasons” are significantly more often reversible than non-reversible, compared to what might be expected by chance. However, in general, the majority of JB constructions are overwhelmingly non-reversible constructions, so JB constructions with the meaning “this and other reasons” are unusual (among JB constructions) for their association with reversibility (compare the total area of the bottom row of boxes to the total area of the top row of boxes):

Figure 2: Mosaic Plot of JB Construction Interpretation and Reversibility

The Mosaic plot in Figure 3 shows the association between the interpretation of the JB construction and the position of the various types of JB construction. The figure shows that JB constructions interpreted as “this and other reasons” are more likely to precede the Y-clause than follow it (however, this is outside the statistical significance level of 0.05). Additionally, we found more preposed JB constructions than post-posed ones.

Figure 3: Mosaic Plot of JB Construction Interpretation and Position of JB Construction

Figure 4 shows the strong association between the interpretation of the JB construction and its structural properties. The figure gives a plot of the structure of the JB construction as found across the three meanings investigated. The left-hand side of the plot gives the various structures available in order of complexity (from phrase to simplex clause, coordinate clause, complex clause and complex compound clause). We see that a great majority of JB constructions are simple, followed by coordinated clauses (very few examples in our data were constructions in which the JB construction was a phrase or a complex clause). While the lack of complex clauses is not all that surprising given its high complexity, the lack of (the simpler) phrasal JB constructions was somewhat surprising given that most of our constructions come from spoken language. The plot also shows that phrasal JB constructions are more likely to be interpreted as “this reason alone” and much less likely to encode the interpretation “no better reason than” (though as before, this did not reach the 0.05 level of significance).

Figure 5: Mosaic Plot of Structure of JB Constructions and Intensity of Negation

Figure 6 shows the final association discussed here between the position of the JB construction and the locus of negation, Cramer’s Value=0.461. As Figure 6 indicates, the preferred locus of the negative marker(s) is inside the JB construction, and this pattern is particularly significant for JB constructions in which the construction is post-posed.

Figure 6: Mosaic Plot of Position of JB Construction and Locus of Negation

Given these associations, it seems relevant to ask to what extent we might detect interactions between the factors Investigated. For example, could it be that “this-reason-alone” JB constructions might be reversible in speech but not in writing? In statistical terms, this is an interaction between interpretation, reversibility and mode. To test this hypothesis, we resorted to a log-linear analysis (Gries 2013: 324-327, Glynn 2014: 321ff) because our parameters are almost exclusively categorical. One constraint of log-linear modeling is its thirst for data – it ideally requires five times the number of observations as the multiplication of the number of levels observed for each variable coded. As we had only 90 items, we were limited to testing at most two or three variables at one time. In light of the associations noted in Table 5, we built a log-linear model using the variables of interpretation, mode and reversibility, whose results are given in Table 6.

Model | AIC | BIC | χ2 | df | p-Value |

Interpretation + Mode + Reversibility | 84.918 | 87.342 | 38.450 | 7 | <0.0001*** |

Interpretation* Reversibility + Mode | 70.686 | 74.081 | 20.219 | 5 | 0.001** |

Interpretation* Mode + Reversibility | 69.883 | 73.278 | 19.416 | 5 | 0.001** |

Interpretation* Mode | 86.750 | 89.659 | 38.282 | 6 | <0.0001*** |

Interpretation* Reversibility | 71.612 | 74.521 | 23.144 | 6 | <0.0001*** |

Table 6: Log-Linear Model with Interactions between Factors

Figure 7 shows that JB constructions interpreted as “this and other reasons” were statistically significantly over-represented in written language as non-reversible structures (and under-represented in written language as reversible ones).

Figure 7: Mosaic Plot of Log-linear Model with Interactions between Factors

Finally, we attempted to model the position of the JB construction (preposed or post-posed) from weight measures (length of the JB construction expressed as number of words) and complexity (structure of the JB construction whether a phrase, simplex clause, complex clause or coordinated clauses) with a logistic regression, but neither of the predictors were significant in our model. This null result is not particularly meaningful because it could have occurred either because, unlike other linguistic studies of this type of phenomenon (e.g. Diessel 2008), the position of JB constructions is indeed not moderated by the structural and interpretative factors coded, or because the statistical model did not have sufficient power to detect it due to insufficient data (90 items). We mention the null result here for completeness. Below is a summary of the main associations uncovered:

i. JB constructions are significantly more frequently used in spoken language than in written language.

ii. JB constructions meaning “this and other reasons” are significantly more likely to be used in writing than in speech and statistically significantly more likely to be coded by a reversible construction.

iii. Over 90% of the JB constructions involve some negation marker, and a great majority will exhibit it either within the construction itself or within the sentence containing it. However, it is also possible to encounter two negative markers, and significantly likely to do so in the case of JB constructions which are part of a coordinated clause.

iv. JB constructions favor carrying the negative marker(s) inside the construction and this is statistically significantly likely to be the case for post-posed JB constructions.

v. Our data contains more preposed JB constructions than post-posed ones, and JB constructions meaning “this and other reasons” show a tendency towards being preposed (but this tendency was not statistically significant).

vi. Most of our JB constructions are coded by simple clauses or coordinate clauses, but for those few examples of phrasal JB constructions encountered, these were typically interpreted as “no better reason” (but this tendency was not statistically significant).

6 Discussion

While it is perhaps not surprising that JB constructions occur more frequently in spoken than in written New Zealand English, what is surprising is the remarkably complex interdependencies among mode, meaning, function, and form of an expression whose apparent simplicity would suggest a corresponding simplicity of distribution. These interdependencies would not have been discovered without the rigor and specificity of our methodology. We propose that this methodology will allow us (and / or other researchers) to compare the properties of JB in New Zealand English with its properties in other English varieties.

Such comparisons may well uncover differences that indicate trajectories of change, such as increasing lexicalization, grammaticalization, and pragmaticalization of the expression just because with concomitant formal reduction and semantic generalization, perhaps allowing JB constructions to escape the negative context generally required to license them in New Zealand English discourse. Our data suggests that a careful manual inspection of data is crucial as a precursor to quantitative investigation, but also shows that once the manual inspection has been conducted, a larger data sample than our current one is needed in order to uncover patterns. However, automating the coding of JB constructions, particularly their three semantic functions (“for this reason alone”, “for this reason and others”, “for no better reason than”), must currently be done manually.

7 Conclusion

Our analysis of JB constructions involves a carefully manually annotated collection of 90 examples from spoken and written New Zealand English. Our analysis shows a predominance of negation in close proximity to the JB construction (either inside it, or in the sentence containing it), and in some cases multiple negators. We also show that JB constructions are more likely to occur in preposed position, but that their position is mediated by their meaning. We also found that JB constructions appear to be favored in spoken language and, given the presence of the negator, we hypothesize that they may be adapted to conversational genres.

One obvious topic for future research is to determine whether the patterns of just because we found in the New Zealand corpora are similar to those in other varieties of English. Relatedly, we would like to see research determining whether just because has become grammaticalized and / or lexicalized in any of those varieties, and if it has, what meanings it supports there.

References

Agha, Asif (2003). The social life of a cultural value. In: Language and Communication 23, 231-273.

Anthony, Laurence (2016). AntConc (Version Mac OS X 3.4.4) [Computer Software]. Tokyo, Japan: Waseda University. (http://www.laurenceanthony.net/software).

Baayen, Harald (2008). Analyzing linguistic data. A practical introduction to statistics using R. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bauer, Laurie (1993). Manual of information to accompany the Wellington Corpus of Written New Zealand English. Wellington: Department of Linguistics, Victoria University of Wellington.

Bender, Emily & Andreas Kathol (2001). Constructional effects of just because . . . doesn't mean . . . In: Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society 27(1), 13-26.

Calude, Andrea & Paul James (2011). A diachronic corpus of New Zealand newspapers. In: New Zealand English Journal 25, 1-14.

Chomsky, Noam (1995). The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Diessel, Holger (2008). Iconicity of sequence: A corpus-based analysis of the positioning of temporal adverbial clauses in English. In: Cognitive Linguistics 19 (3), 465-490.

Disken, Chloé, Jen Hay, Katie Drager, Paul Foulkes, Ksenia Gnevsheva, James Grama, . . . Simon Gonzalez (2019). The emergence of the discourse-pragmatic marker ‘just’: Linking changes in usage to changes in pronunciation. Paper presented at NZLS 2019 Christchurch, NZ, November 27-29, 2019.

Farrell, James Gordon (22002 &1970). Troubles. New York: NYRB Classics.

Glynn, Dylan (2014). Techniques and tools: Corpus methods and statistics for semantics. In: Glynn, Dylan & Justyna A. Robinson (Eds.). Corpus methods for semantics: Quantitative studies in polysemy and synonymy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 307-341.

Gries, Stefan (22013). Statistics for linguistics with R. Berlin & Boston: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hilpert, Martin (2005). From causality to concessivity: The story of just because. In: University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 11(1), 85-98.

Hilpert, Martin (2007). Just because it's new doesn't mean people will notice it. In: English Today 23 (3-4), 29-33.

Hirose, Yukio (1991). On a certain nominal use of because-clauses: Just because because-clauses can substitute for that-clauses does not mean that this is always possible. In: English Linguistics 8, 16-33.

Holmes, Janet, Bernadette Vine & Gary Johnson (1998). Guide to the Wellington Corpus of Spoken New Zealand English. Wellington: Department of Linguistics, Victoria University of Wellington.

Horn, Laurence R. & Heinrich Wansing (2017). Negation. In: Zalta, Edward N. (Ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 Edition). (https://plato.stanford.edu/ archives/spr2017/entries/negation/; 11-2-2019).

Huddleston, Rodney & Geoffrey Pullum (2002). Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press.

Iten, Corinne (1998). Because and although: A case of duality? In: Villy, Rouchota & Andreas H. Jucker (Eds.). Current issues in relevance theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johnstone, Barbara (2014). Enregisterment: Linguistic form and meaning in time and space. In: Busse, Beatrix & Ingo Warnke (Eds.). Sprache im urbanen Raum / Language in urban space. Berlin, Germany: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kanetani, Masaru (n.d.) A note on because-clauses. (http://www.u.tsukuba.ac.jp/~kanetani.masaru.gb/pdf/justbecause.pdf; 6 May 2018).

Kanetani, Masaru (2007). Focalization of because and since: Since-clauses can be focalized by certain focusing adverbs, especially since there is no reason to ban it. In: English Linguistics 24 (2), 341-362.

Kanetani, Masaru (2019). Causation and reasoning constructions. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Kishner, Jeffrey M. & Gibbs W. Raymond, Jr. (1996). How just gets its meanings: Polysemy and context in psychological semantics. In: Language and Speech 39 (1), 19-36.

Lee, David (1987). The semantics of just. In: Journal of Pragmatics 11, 377-398.

Lee, David (1991). Categories in the description of just. In: Lingua 83, 43-66.

Levshina, Natalia (2015). How to do linguistics with R–Data exploration and statistical analysis. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lindemann, Stephanie & Anna Mauranen (2001). ‘It's just real messy’: The occurrence and function of just in a corpus of academic speech. In: English for Specific Purposes 20, 459-475.

Matsuyama, Tetsuya (2001). Subject-because construction and the extended projection principle. In: English Linguistics 18 (2), 329-355.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech & Jan Svartvik (1985). A grammar of contemporary English. London, UK: Longman.

R Core Team (2017). R: A Language and environment for statistical computing [Computer Software]. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. (http://www.R-project.org).

Silverstein, Michael (2003). Indexical order and the dialectics of sociolinguistic life. In: Language and Communication 23, 193-229.

Authors:

Andreea Calude

Senior Lecturer

Convenor of Linguistics

Department of Linguistics/Applied Linguistics

University of Waikato

Email: andreea@waikato.ac.nz

Hamilton, New Zealand

Gerald Delahunty

Professor of Linguistics and English

Director of Language Programs

English Department

Colorado State University

Email: gerald.delahunty@colostate.edu

Fort Collins, Colorado, USA

____________________

(1) Just because is one of many more or less fixed expressions beginning with just: just in case/time; just the thing/job/ticket; just my luck; just about right/done; just a minute/moment; just now/then; just who/what/when/why, etc.

(2) Lee (1987, 1991) and Kishner & Gibbs (1996) are studies of the meanings of just; Lindemann & Mauranen (2001) is a study of just in an academic corpus; Disken et al. (2019) is a corpus study of collocates of just and its emergence as a pragmatic marker; Iten (1998) is a relevance theoretic study of the causal and concessive meaning relations between because and although.

(3) Compare this number with "About 6,160,000,000 results (0.89 seconds)" on November 3, 2019.

(4) Numbers in this format refer to examples in our data – which we make fully available.

(5) A note on our terminology: "JB construction" refers to the grammatical unit, typically a clause or prepositional phrase, introduced by just because; "JB sentence" refers to the sentence in which the JB construction functions as subject or other grammatical relation.

(6) There was one case whose meaning we could not determine.

(7) RA, RO, and NBR are the acronyms we used to code the meanings associated with the JB expression indicated in the table.

(8) All graphics included in the paper and the modelling was done using R Software (R Core Team 2017).

(9) Cramer’s V range 0-1 is interpreted as follows: 0-20 low association, 0.20-0.50 moderate association, 0.50-1 high association.

(10) Fisher’s exact p-values are marked by *, **, *** depending on the strength of significance (following R convention).