Volume 6 (2015) Issue 1

Examining

Successful Language Use at C1 Level: A Learner Corpus

Study into the Vocabulary and Abilities Demonstrated by Successful Speaking

Exam Candidates

Shelley

Byrne (Preston (Lancashire), United Kingdom

Abstract

This study situates itself

amongst research into spoken English grammars, learner success and descriptions

of linguistic progression within the Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001). It follows previous corpus research

which has sought to document the language required by learners if they are to

progress through levels and ultimately ‘succeed’ when operating in English. In

the field of language testing, for which the CEFR has been a valuable tool,

qualitative descriptions of learner competence and abilities may not provide

sufficient detail for students, assessors and test designers alike to know

which language is required and used by learners at different levels. This

particular study therefore aims to identify the language and abilities demonstrated

by successful C1 candidates taking the University of Central

Lancashire

Key words: Learner corpora, spoken grammar,

language testing

1 Introduction

Success in

second language acquisition has been subject to various avenues of

investigation. From the examination of individual cognitive and affective

characteristics (Cook 2008; Dornyei & Skehan 2003; Ellis 2008; Gardner

& MacIntyre 1992; Robinson 2002; Rubin 1975) to the application of learner

models or “yardstick[s]” (House 2003: 557), researchers and practitioners have

aimed to demystify what makes language learners successful. Another approach in

this pursuit has been to explore more deeply the features that language

comprises using corpus linguistics, a technique which has often been used to

explicate how lexico-grammatical forms differ or correspond in spoken and

written discourse (Biber, Johansson, Leech, Conrad & Finegan 1999, Leech

2000, Conrad 2000, McCarthy & Carter 1995). The compilation of descriptive

grammars and various corpora (Biber et al. 1999, Carter & McCarthy 2006,

Cambridge English Corpus (CEC) 2012, the British National Corpus (BNC) 2004,

and the Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English (CANCODE)

2012), has resulted in enhanced knowledge of spoken and written English

features that has not only aided comparison, but has simultaneously provided a

source of knowledge for learners.

However,

the native-speaker (NS) foundations upon which such grammars and corpora are

assembled have generated debate and criticism. Despite some learners’

aspirations to conform to native speaker models (Timmis 2002), questions have

arisen regarding the applicability of a linguistic model potentially inappropriate,

unachievable, conflicting or irrelevant in a world where English as a lingua

franca is used often beyond native-speaker contexts (Alpetkin 2002,

Canagarajah 2007, Cook 1999, Cook 2008, Kramsch 2003, Norton 1997, Phillipson

1992, Piller 2002, Prodromou 2008, Stern 1983, Widdowson 1994). Research into

successful spoken and written language use has therefore begun to place

emphasis on learner corpus research centring on language use by non-native

speakers who operate and function as “successful users of English” (Prodromou

2008: xiv) (International Corpus of Learner English (ICLE) (Granger, Dagneaux, Meunier, & Paquot 2009), the

Vienna-Oxford Corpus of International English (VOICE 2013), and Cambridge

English Profile Corpus (CEPC n.d.)).

Within the

European language provision context, research is also delineating learner

success and language use in terms of the proficiency descriptors provided by

the Common European Framework of

Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe [CoE] 2001), a document

outlining the wide-ranging competencies of language learners in a variety of

language learning settings. In a bid to satisfy its aims of providing a

non-prescriptive, adaptable guide for language provision, no illustration is

given as to the actual language to be evidenced at different levels (Alderson

2007, Weir 2005). Put simply, while readers can discover what learners should

be able to do with their language,

less guidance is offered for what language

should be used in order to do it. It is this intentional limitation which has

stimulated this study focusing on a particular set of speaking exams. As the

uptake of CEFR levels and proficiency scales was considerable in the field of

language assessment (Little 2007), this study aims to reveal what language is required

by speaking test candidates if they are to be successful

in C1 level exams. Building upon the findings of a B2 study conducted by

Jones, Waller & Golebiewska (2013), it reports on data from a spoken C1

test corpus of learner language in order to answer the following research

questions:

RQ1 What percentage of the

words used by C1 learners come from the first thousand and second thousand most

frequent words in the BNC?

RQ2a What were the twenty most frequent words used by successful

learners at C1 level?

RQ2b What were the important keywords at C1 level?

RQ2c What were the most frequent three- and four-word chunks used by

these learners?

RQ3 What C1 CEFR indicators are

present in terms of spoken interaction, spoken production and strategies?

2 Literature Review

The impetus

for identifying a spoken grammar of English arose from criticisms towards

traditional grammars heavily influenced by the written word and their

applicability to the diverse, wide-ranging speakers and contexts encompassed by

the medium of informal conversation. Ensuing research, facilitated

by developments and findings in corpus linguistics techniques (Leech

2000), prompted the compilation of large spoken corpora including the CEC, BNC

and CANCODE. In addition to providing real examples of language for

practitioners and learners, such corpora have done much to expand knowledge of

written and spoken lexico-grammars and their distinctions. With knowledge of

the target language system being integral to success in language learning (Griffiths

2004), an increased knowledge of grammar is believed to do much to raise

learners’ potentials to “operate flexibly in a range of spoken and written

contexts” (McCarthy & Carter 1995: 207).

One area of lexico-grammatical knowledge broadened by corpus

linguistics relates to vocabulary, in particular the use of lexical chunks.

Vocabulary, learned for its communicative purpose (Laufer & Nation 1995)

aids the construction and comprehension of meaning, enhances the acquisition of

new vocabulary, extends the knowledge of the

world and is fundamental to student performance (Chujo 2004). In terms of

success and language learning, it seems crucial that research should aim to

identify what and how much vocabulary is needed to achieve

a particular purpose (Adolphs & Schmitt 2004). Studies based on the NS

corpora above have, however, demonstrated that

vocabulary is rarely used in isolation. It is often combined to form

prefabricated chunks (Wray 2002), formulaic expressions (Schmitt 2004) or

“standardised multiword expressions” (Boers, Eyckmans, Kappel, Stengers &

Demecheleer 2006: 246) which can fulfil various linguistic functions including

collocations, fillers in speech and idiomatic expressions. Constituting varying

proportions of total language use (Erman & Warren 2000, Foster 2001),

lexical chunks not only influence the assessment of learner proficiency and

success, but they also facilitate spoken production. They reduce memory

constraints, they can make students sound more native-like, they can maintain

accuracy and they can act as “zones of safety” (Boers et al. 2006: 247; also

Wray 2002 and Skehan 1998). With estimations asserting that chunks comprise

32.3% and 58.6% of NS spoken discourse, investigations of learner success

should indeed take them into account to ascertain whether they are used and

whether lexical chunk instruction may be of benefit to learners.

Returning

to the notion of learner success, corpus findings and spoken grammars based on

the NS may seem somewhat paradoxical in the pursuit of a “natural spoken

output” in the classroom (McCarthy & Carter 2001: 51). Questions have been raised as to whether NS findings can

indeed provide appropriate grammatical insights beneficial to the

development of ‘natural’ non-native speech. Although many teachers and learners

may endeavour to achieve a native-like standard in English (Timmis 2002), the

NS model for many learners can be deemed “utopian, unrealistic,

and constraining” (Alptekin 2002: 57) and at times unconducive to the goals of

individuals who may operate in English beyond traditional, inner-circle NS

contexts (Andreou & Galantomos 2009, Kachru 1992). Recent years have

therefore seen an increase in the application of learner corpora to obtain

greater insight into proficiency and linguistic achievement during second

language learning (e.g. ICLE, VOICE, and CEC). By exposing learners to examples

from successful learners of English rather than those of native speakers, it is

thought they will be able to consult a model which is more realistic, appropriate

and, ultimately, within reach.

A further

branch bridging the discussion of successful language use and corpus

linguistics concerns associations with learner competency descriptors within

the CEFR (CoE 2001). In addition to detailing

extensively the skills learners possess and cultivate across a wide range of

social and educational contexts, the CEFR comprehensively describes

communicative language activities and competences. Specifically, in relation to

the focus of this study, its six Common

Reference Levels and can-do statements

outline the abilities of language learners at different stages. However,

despite its intentional, non-exhaustive nature (CoE 2001, Coste 2007, North

2006, Weir 2005), it has faced criticism. While

some highlight its misuse, its lack of support from second language acquisition

theory and its sometimes problematic application caused by vague definitions

and vocabulary, others have stressed the absence of actual language use to

enhance the understanding of its competency

descriptors (Alderson 2007, Fulcher 2004, Figueras 2012, Hulstijn 2007;,Weir 2005). In short,

the detailed guidance offered in describing abilities at each of the six levels

is not replicated in the form of illustrative linguistic structures and

vocabulary to be encountered or mastered by learners. One large-scale study,

the CEPC (n.d.) has begun to tackle these issues. Via the compilation of an

intended 10 million word (20% spoken, 80% written) learner corpus covering levels A1-C2, the CEPC intends to document

the language required by learners to satisfy descriptors at each level.

While the

present, much smaller study may seem to share aims

similar to the CEPC, its context is more focussed. While the CEPC incorporates

general and specific written and spoken English language use by learners from

across the world, the lexico-grammatical findings in this study will relate

only to successful spoken language use in C1 speaking examinations produced by

UCLanESB so that test writers, assessors,

teachers and students can all be made aware of how language can be used to

fulfil CEFR criteria.

3 Methodology

A learner

corpus of 26,620 words was constructed, using sample language from the UCLanESB

spoken tests at C1 level. Samples were taken from 31 adult candidates (16 males,

15 females) of mixed nationalities who achieved a solid pass score on the test each. Following completion of the speaking

tests, conducted in groups of two or three candidates, speakers were given a mark of 0-5 for vocabulary, grammar,

discourse management, interactive ability, and pronunciation; a global score was then calculated. It was this global score

which was used as a measure for success. As a score of 2.5 equates to a pass, only exams in which both or all

candidates achieved a score of 3.5 or 4 were incorporated into the corpus.

Students attaining a mark outside this score bracket may not have displayed a

solid, successful performance at C1 level and would therefore not assist the

aims of the research. Steps were also taken to verify the global scores of

exams incorporated into the corpus: all exam assessors had completed UCLanESB

standardisation, all exams had been second-marked and the researcher did not

take part in any exam, neither as an assessor nor as

an interlocutor.

To

correspond with other general English tests, and to assess an array of speaking

skills (O’Sullivan Weir & Saville 2002), the test

was divided into three scripted parts (the

format description being taken from Jones, Waller & Golebiewska

2013: 32):

Part A: The

interlocutor asks for mainly general personal information about the candidates

(question-answer form). Candidates answer in turn. This stage lasts for

approximately two minutes.

Part B: Candidates

engage in an interactive discussion based on two written statements. The interlocutor

does not take part. This stage lasts for approximately four minutes.

Part C: Candidates

discuss questions related to the topic in Part B both together and with the

examiner. This stage lasts for approximately four minutes.

The C1

tests were transcribed using the CANCODE

transcription conventions (Adolphs 2008) to facilitate analysis. Accessible to

prospective readers, and still precise and reliable for illustrating

interactions between the candidates and interlocutors, they were conducive to analysis

during explorations of data which often involved the omission of interlocutor

data. Once transcribed, data were subjected to various analyses. A lexical

profile (Laufer & Nation 1995) was first created, using the Compleat Lexical Tutor (Cobb 2014) to

identify the percentage of words used,

belonging to the first and second thousand most frequent words in the spoken

BNC (Leech, Rayson & Wilson 2001) alongside calculations of token-type ratios to allow for preliminary

comparisons of lexical repetition. Wordsmith Tools (Scott 2014) software

was utilised to calculate word frequency and keyword lists which employed a

keyness ratio of 1:50 (Chung & Nation 2004) and the spoken BNC as a

reference. To answer the final part of the second research question, three- and

four-word lexical chunks were then sorted according to their frequency via

Anthony’s (2014) Antconc software. The final stage involved a

qualitative analysis of learner language, using NVIVO software (QSR 2012). This

helped to determine the occurrence of relevant, spoken C1 can-do

descriptors and the language used to realise them. Relevant speaking

descriptors were taken from the production, interaction and strategy use

sections of the CEFR (CoE 2001: 58-87).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1 Research Question 1 (RQ1)

Research

Question 1 was the following one:

What percentage of the words

used by C1 learners come from the first thousand and second thousand most

frequent words in the spoken BNC?

The

percentage of words from the first thousand (K-1) and second thousand (K-2)

most frequent words in English are shown in Table 1 below:

|

Frequency Level

|

Families (%)

|

Types (%)

|

Tokens (%)

|

Cumulative Tokens %

|

Type-Token Ratio

|

|

K-1 Words

K-2 Words

|

607

(58.48)

236

(22.74)

|

927

(63.71)

285

(19.59)

|

19307 (92.25)

976 (4.66)

|

92.25

96.91

|

14.38

|

Tab. 1: Percentage of words from the

first and second thousand most frequent English

words

As can be

seen, a cumulative majority of words, 96.91%, originated from the first 2000

most frequent words in English. Although this

majority is dominated by words from the K-1 band, in sum, the data still demonstrate that less than one in every twenty words

belonged to bands beyond the 2000 word limit. For students to be successful at

C1 level, therefore, it is crucial that candidates have knowledge of words

originating from the K-1 and K-2 bands, an assertion supported by several

writers (McCarthy 1999, O’Keefe, McCarthy & Carter 2007).

Further

insights into C1 success can also be obtained by examining the coverage

provided by word families: groups consisting of headwords, their inflections

and derivations (Nation 2001, Nagy et al, 1989). Whilst it is acknowledged that

learners require a wide-ranging vocabulary in order to satisfy long-term learning

goals (Nation 2001), much research recognises the need for students to make use

of a limited, useful vocabulary, a vocabulary which is continually repeated and

recycled in order to satisfy a range of spoken and written functions (Nation

2001, Nation & Waring 1997, Cobb n.d.). Such a useful vocabulary in English

is said to mostly comprise the first 2000 word families: in written texts, this

figure provides a coverage of approximately 80% (Francis & Kucera 1982,

Cobb n.d., Nation & Waring 1997, Nation 2001), whilst in unscripted spoken

texts, the percentage coverage rises to 96% (Adolphs & Schmitt 2004) or 97%

(Schonell et al, 1956, cited in Adolphs & Schmitt 2004). The data in Table

1 indicate that K-1 word families (58.48%) and

K-2 word families (22.74%) only supplied a combined coverage of 81%. This

figure, greatly reduced in comparison with the estimations of Schonell et al.

(1956) and Adolphs & Schmitt (2004), is, however, somewhat anticipated. C1

learners will not have a vocabulary breadth comparable to that of native

speakers, nor will they be able to draw on an equal, or readily available,

knowledge of the inflections or derivations belonging to a particular headword.

The above

deduction could therefore have implications for the expectations placed upon

successful C1 learners in relation to CEFR descriptors. With C1 encompassed by

the proficient user label in the CEFR (CoE, 2001: 23), it may be easy to

assume candidates to be able to employ more advanced lexis. However, with such

a high proportion of K-1 and K-2 words and a type-token ratio of 14, which

suggests a certain degree of repetition at this level, emphasis might not be placed on the advanced nature of

vocabulary, but on the flexibility and

frequency with which the first 2000 words can be used as per the C1 level

descriptor presented earlier. For instance, although example statements such as

the excerpt below do not seem impressive in terms of lexical difficulty (bold

type represents words beyond K-2), they do contain vocabulary which i) meets the

demands of the task and ii) can be reproduced for use in other parts of the

test[1]:

Example:

<$3M> Okay can I go first? Okay erm

tourism in my country is not really important why because erm my country has a

lot of problems like erm there are a lot of things that er need to be atte=

attended to before tourism so basically what they are focussing on is not

tourism at all they are trying to focus on agriculture

and the production the industries and the rest so like tourism is like neglected in my country.

4.2

Research Question 2a:

What were the twenty most

frequent words used by successful learners at C1 level?

|

Rank

|

Word

|

Frequency

|

Coverage (%)

|

|

|

Individual

|

Cumulative

|

|||

|

1

|

THE

|

1071

|

5.18

|

5.18

|

|

2

|

ER

|

733

|

3.55

|

8.73

|

|

3

|

I

|

718

|

3.47

|

12.20

|

|

4

|

AND

|

590

|

2.85

|

15.05

|

|

5

|

TO

|

581

|

2.81

|

17.86

|

|

6

|

ERM

|

450

|

2.18

|

20.04

|

|

7

|

IS

|

377

|

1.82

|

21.86

|

|

8

|

IN

|

369

|

1.79

|

23.65

|

|

9

|

YOU

|

360

|

1.74

|

25.39

|

|

10

|

YEAH

|

354

|

1.71

|

27.10

|

|

11

|

THINK

|

313

|

1.51

|

28.61

|

|

12

|

AND

|

309

|

1.49

|

30.10

|

|

13

|

LIKE

|

302

|

1.46

|

31.56

|

|

14

|

OF

|

281

|

1.36

|

32.92

|

|

15

|

SO

|

255

|

1.23

|

34.15

|

|

16

|

THEY

|

250

|

1.21

|

35.36

|

|

17

|

IT'S

|

234

|

1.13

|

36.49

|

|

18

|

IT'S

|

230

|

1.11

|

37.60

|

|

19

|

THAT

|

174

|

0.84

|

38.44

|

|

20

|

BECAUSE

|

173

|

0.84

|

39.28

|

Tab.

2: Most frequent words used by successful C1 learners

Upon

initial inspection, these word frequency results may seem rather unsurprising.

When compared with frequency lists for the spoken BNC (Leech, Rayson &

Wilson 2001) and the Cambridge

Firstly,

the CEFR C1 descriptor clearly states its position regarding hesitancy: fluent

expression should be executed “without much obvious searching” (CoE 2001: 27).

The fillers er and erm, nevertheless, occupy

the second and the sixth position, respectively, in the C1 frequency

list. This, too, is rather predictable in that of a variety of “performance

additions” such as fillers, discourse markers and delays, er and erm

are regarded as the most common (Clark & Foxtree 2002: 74). They can also

be used to cope with memory demands which can cause uncertainty, delay or

inability when answering questions (Smith & Clark 1993), and it can be

assumed that learners will have to exploit a much narrower vocabulary to fulfil

their linguistic needs, a task potentially increasing the occurrence of pauses.

While delaying expressions such as well, what do you call it and how

will I put it are found in the C1 data, they are not as flexible as er

and erm; arguably, they may neither seem as natural. Ultimately, despite

the C1 descriptor, it should be expected that successful C1 students will still

use er and erm frequently.

Developing

from hesitation, it is relevant to discuss how word frequency may be influenced

by the nature of the C1 exam and the task demands placed upon candidates. For

instance, words such as think, so and because would be

expected in an exam which frequently elicits opinions and reasonings in order

to assess abilities to “formulate ideas and opinions with precision” (CoE 2001:

27). In the case of think (38th position in CANCODE; 46th position in

the spoken BNC), the data and the aims of some vocabulary instruction for

giving opinions may conflict. Some exercises make an effort to present learners

with alternatives to I think which represented 260 occurrences in the C1

data, such as in my opinion (ten occurrences), I believe (seven

occurrences), from my point of view (one occurrence) and as far as

I’m concerned or if you asked me (zero occurrences).

In the C1 data, these other forms were heavily eclipsed in terms of frequency.

This finding raises the question as to whether students should be expected to

use these alternative phrases when I think delivers success at C1. It

may seem basic, but it is efficient and more target-like when compared with NS

corpus data.

C1

descriptors also require learners to provide sufficient conclusions to their

utterances. A productive can-do statement looks for evidence that C1

learners are able to supply an “appropriate conclusion” to “round-off” their

arguments (CoE 2001: 27). In relation to task demands, this can offer some

explanation as to why the conjunction so appears frequently in the C1

corpus (in the spoken BNC, this function occupied 274th position).

Corresponding to word usage for expressing purpose, as

documented in Carter & McCarthy’s Cambridge Grammar of English (2006: 143), a high majority of

occurrences of so did involve its use as a subordinating conjunction to

introduce “result, consequence and purpose”. Whilst this contrasts greatly from

Carter & McCarthy’s (2006) observation that so in NS spoken English

is used most frequently as a discourse marker (e.g. so what are we supposed

to be doing?), the C1 data show that not only is this usage very frequent,

but that this could be a direct result of the demands placed upon students by

the exam tasks. Similarly, the high frequency of because in the C1 data

should have been foreseeable; students are repeatedly asked for explanations

for their opinions. Also, although cos does appear in the C1 frequency

data (76th position) and its use is expected in informal speech (Carter &

McCarthy 2006), because is used more often to give reasons and extra

information in support of opinions in the main clause, as in the following

example (words in bold have been discussed in

this section):

Examples:

<$11F> I think if you er put a

bins and it er has a labels or er write about which one is er for recycling mm people will do

right so I think it's a good way to

protect the environment. How about you?

<$12F> Okay I take your point but erm this is some problem about the bins

because erm I often see a lot of

people they can't recognise the symbol on the bins because erm they sometimes they walking on the road they just erm keep they eyesight in the street so they can't erm remember the symbol

on the bins.

A final

finding to be highlighted here refers to a notable difference in the C1 data

which contrasts the findings of Jones, Waller and Golebiewska’s (2013) study

into UCLanESB’s B2 spoken test data. Despite the arguable value of teaching

students high frequency verbs such as go, have and do

(Willis 1990) for use as full, auxiliary and delexicalized verbs (Lewis 1993,

1997), such verbs did not appear in the most frequent C1 words seen in Table 2.

In fact, go, although still much more frequently used than have

and do in the B2 data, only appears in 49th position. Such a

finding may initially suggest that C1 students have a greater repertoire of

vocabulary that can satisfy similar meanings or functions. Although this would

require greater exploration, this conclusion may appear valid in the C1 data,

especially when the low occurrence of circumlocution and paraphrase (see RQ3;

findings) is considered. The successful C1 students in this study may,

therefore, have demonstrated the necessary “good command” of vocabulary to

satisfy the CoE’s (2001: 28) C1 descriptor of range.

4.3

Research Question 2b

What were the important

keywords at C1 level?

|

Rank

|

Keyword

|

Frequency

|

RC. Frequency

|

RC %

|

|

1

|

ER

|

733

|

90,254

|

0.09

|

|

2

|

ERM

|

450

|

63,095

|

0.06

|

|

3

|

YEAH

|

354

|

83,012

|

0.08

|

|

4

|

THINK

|

313

|

88,700

|

0.09

|

|

5

|

I

|

717

|

732,523

|

0.74

|

|

6

|

LIKE

|

302

|

147,936

|

0.15

|

|

7

|

IT'S

|

234

|

126,792

|

0.13

|

|

8

|

MAYBE

|

87

|

10,023

|

0.01

|

|

9

|

TOURISM

|

55

|

1,461

|

|

|

10

|

BECAUSE

|

173

|

100,659

|

0.1

|

|

11

|

HOTEL

|

82

|

10,911

|

0.01

|

|

12

|

SO

|

254

|

239,549

|

0.24

|

|

13

|

COUNTRY

|

99

|

27,959

|

0.03

|

|

14

|

|

31

|

141

|

|

|

15

|

PEOPLE

|

162

|

116196

|

0.12

|

|

16

|

MM

|

100

|

34736

|

0.03

|

|

17

|

YOU

|

360

|

588503

|

0.59

|

|

18

|

UM

|

32

|

651

|

|

|

19

|

REALLY

|

98

|

46477

|

0.05

|

|

20

|

IMPORTANT

|

89

|

38721

|

0.04

|

Tab.

3: Top 20 keywords used by successful C1 learners

Preliminary

observation seems to corroborate conclusions from the examination of the

frequency lists. Not only do words such as er, erm, think,

like, so and because appear much more highly in the C1

frequency lists when compared to the reference corpora lists used, but they

also seem to be of particular significance to the success of C1 test

candidates. Once again, the implied importance of these words could be a

product of test design and the task demands placed on students. It could also

be assumed that the keyword ranking of this lexis could be due to their

fluctuating usage: their high frequency and usefulness not only corresponds to

the nature of the C1 exam, but also to the valuable range of functions the

words fulfil for successful candidates.

For

instance, the cases of think and like may demonstrate the variety

afforded, a variety which may help to satisfy criteria relating to C1 expectations

of students to be able to use language “flexibly and effectively” (CoE 2001:

27). When exploring Key Word In Context (KWIC) concordance data to discover the

way in which these words were used, think and like varied.

Unsurprisingly, think was used to give and obtain opinions throughout

the exam (the most frequent question asked by students was What do you

think?). As the examples below demonstrate, it also was utilised to create

hedging phrases, expressions of uncertainty, and it was occasionally modified

to add emphasis:

Examples:

<$7F> Yeah it will help the

environment environment I think.

<$2M> Erm I really think that this is the most important bit about the hotel

er the place where I would spend the night if it's er I really think that if erm the room's totally quiet like the walls

are too thick that the sound can't pass over them <$O2> it's perfect for

me </$O2>

In relation

to like, it became increasingly apparent, when scrutinising

the KWIC data that its use not only altered according to its word class,

but also according to the exam section. The data showed that like was

used as a lexical verb, a preposition, and as a filler (as shown below):

Examples:

<$19M> Er usually I like [verb] light music and pop music.

The light music er especially for before I go to bed and pop music for example

when I travelling somewhere I usually use my headphones to listen it.

<$29M> Well first of all I live in Qatar it's a sm= small country and my

neighbourhood is actually in <$G3> it's in Doha

<$24M> But for me like [filler] all these are related like [preposition] stress rent smoking

and maybe you you have stress because you don't sleep enough.

Like allowed students to provide examples and analogies and it also

acted as a filler during voiced pauses (Carter & McCarthy 2006). Although

it was predominantly used as a lexical verb in Part A of the exam, its usage in

parts B and C changed when it began to be used more as a filler, similar to the

way young native speakers use it today (Carter & McCarthy 2006). Since Part

B removes the interlocutor’s support and Part

C “aims to push candidates towards their linguistic ceiling” (Jones, Waller

& Golebiewska 2013: 33), it is anticipated that the occurrence of pauses

will increase. However, at C1, perhaps the use of like in this way

evidences a mastering or attempts by learners to employ NS filler lexis.

4.4

Research Question 2c

What were the most frequent

three- and four-word chunks used by these learners?

Table 4

presents the most frequent three- and four-word chunks used by successful C1

students. The chunks in bold also appeared in

the top 20 in the spoken BNC’s chunk data (Adolphs & Carter 2013):

|

Three-word chunks

|

Four-word chunks

|

|

1. [47] I THINK IT

|

1. [35]I THINK IT’S

|

|

2. [41] IN MY COUNTRY

|

2. [15] WHAT DO YOU THINK

|

|

3. [36] I DON’T

|

3. [11] I AGREE WITH YOU

|

|

4. [36] THINK IT’S

|

4. [11] I DON’T KNOW

|

|

5. [35] A LOT OF

|

5. [11] LOCATION OF THE

HOTEL

|

|

6. [32] SO I THINK

|

6. [11] YEAH I AGREE

WITH

|

|

7. [27] IT’S A

|

7. [10] IT’S IT’S

|

|

8. [25] DO YOU THINK

|

8. [10] THE LOCATION OF

THE

|

|

9. [25] OF THE HOTEL

|

9. [8] DO YOU THINK

ABOUT

|

|

10. [24] I THINK THE

|

10. [7] A LOT OF PEOPLE

|

|

11. [23] I THINK THAT

|

11. [7] IN MY COUNTRY IS

|

|

12. [23] IT’S NOT

|

12. [7] SO I THINK IT

|

|

13. [22] I AGREE WITH

|

13. [6] A LOT OF THINGS

|

|

14. [22] IT’S VERY

|

14. [6] I THINK THAT THE

|

|

15. [22] YEAH IT’S

|

15. [6] MOST OF THE TIME

|

|

16. [21] ER I THINK

|

16. [6] THINK IT’S VERY

|

|

17. [21] ERM I THINK

|

17. [6] TOURISM IN MY

COUNTRY

|

|

18. [20] WHAT DO YOU

|

18. [6] YEAH IT’S VERY

|

|

19. [18] DON’T HAVE

|

19. [5] A FOUR STAR

HOTEL

|

|

20. [18] I THINK ERM

|

20. [5] BUT I THINK IT

|

Tab.

4: Most frequent three- and four-word chunks

An initial comparison of

the C1 results above and the 20 most frequent chunks in the BNC (Adolphs &

Carter 2013) and CANCODE (McCarthy 2006) reveal that whilst chunk frequency was

relatively low in the C1 data, there is evidence that successful candidates

replicate some of the most common chunks typical of NS speech.

With

regards to the composition of the C1 chunks, the data suggest that they represent another

way in which knowledge of the K-1 and K-2 word

families can be exploited. A profile using the Compleat Lexical Tutor revealed that 94%

of three- and four-word chunk lexis originated from the K-1 band, task-related

lexis from the K-2 (e.g. location and hotel)

constituted 4%, and erm (2%) was considered off-list. A similar analysis

of the BNC’s most frequent three- and four-word chunk lexis determined that

100% of the words came from the K-1 band. To

make use of chunks, therefore, no complex, less-familiar vocabulary is needed;

although NS chunks may prove problematic for learners to “identify and master”

(Wray 2000: 176), the lexis they comprise should correspond to the vocabulary that C1 students already possess.

Lexical

chunks are also deemed advantageous for their impact

on fluency, memory and, particularly, listener perceptions of

proficiency (Schmitt 2000, Boers et al. 2006, Wray 2000). Chunks are believed

to be stored holistically, their availability demands less cognitive capacity

and they can “transform” perceptions even of low-level learners’ fluency

(O’Keefe, McCarthy & Carter 2007: 77). The fact that they appear in C1

speech, although less frequently than in B2 speech (Jones, Waller & Golebiewska

2013) may show that they could be a component of successful C1 candidates being

judged to be fluent and spontaneous (CoE 2001). Furthermore, they are flexible

and perform a range of lexical and functional roles (see RQ 3) and they can, at

C1, include fillers. Although lexical chunks are usually identified through a

lack of hesitation (Ellis & Sinclair 1996), C1 students may be able to give

the impression of fluency despite the use of vocalised fillers. Ultimately,

students who are able to incorporate chunks into their production will be seen

as more proficient and more successful to those who cannot (Boers et al. 2006).

4.5

Research Question 3

What C1 CEFR indicators are

present in terms of spoken interaction, spoken production and strategies?

A qualitative

analysis of the C1 test data aimed to establish which speaking can-do

statements were demonstrated for production, interaction and strategy use.

Although students received solid pass grades which denoted a certain degree of

achievement, it was necessary to see how their exam performance corresponded to

CEFR descriptors. The corpus data have already identified the lexis contained

in their language, but success also involves learning what the C1 students

actually did with their language.

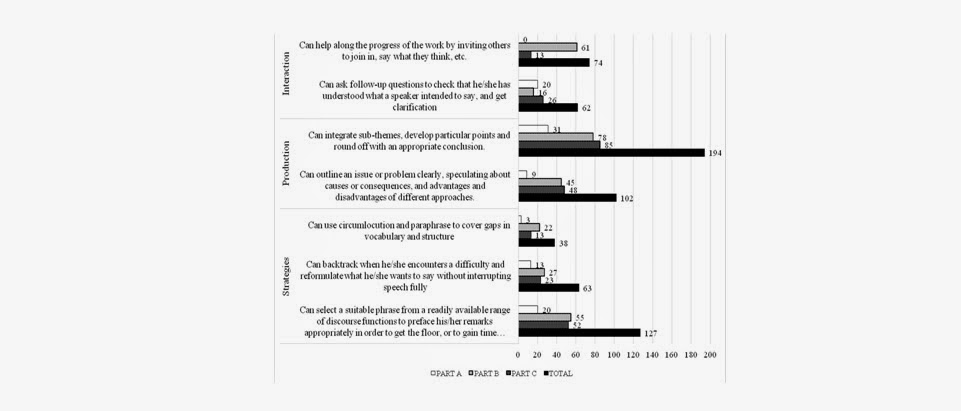

Fig. 1: C1 can-do occurrence

across all parts of the exam

Of 660 can-do

instances, approximately 45% related to production. Although the nature of

the test did influence this category (there was less evidence of sub-theme

integrations, conclusions, speculation and outlining of issues in the shorter,

less demanding section, Part A), the data suggest that C1 candidates should

develop and lengthen their answers to demonstrate productive abilities if they

are to be considered successful. Although the CEFR does not specify for which

‘complex subjects’ this should be done, the example statement below does

illustrate how this could be achieved.

Example:

<$3M> Okay erm immediate transport

problems in my country would be the fact that <$=> erm the erm

<$G?> </$=> it would be er like the transportation agency or should

I say like erm the people er like that handle transport are not very strict.

Erm young people like er people like four years older younger than me like

sixteen years olds or fifteen year olds are allowed to drive. Basically it's

not allowed in the er law in my country but even if you're fifteen or thirteen

they could drive around in a car and if like a policeman should stop you or a

road safety person should stop you you could bribe them like really low amounts

like anybody could afford it and they will let you go.

It was also

pertinent to note that interactive and strategic can-do language

occasionally appeared similar across some learners in the sample. For instance,

some candidates employed the same lexical chunks, although somewhat low in

terms of frequency, to satisfy the demands placed upon them. In order to

develop the progress of the exam and invite

responses (interaction) the chunk what do you (20 occurrences) was

combined with think, admire, feel and reckon. This

particular chunk may afford the students a greater degree of fluency and

flexibility; it may not require additional processing and it is a chunk which

may be adapted via the inclusion of a “slot” or space for numerous words

depending on the desired meaning (Schmitt 2000: 400). Students also showed

similarity in the way they used language to gain time during the exam. The

chunk I agree with (22 occurrences) was judged to be a stalling

technique on eleven occasions and a quarter of instances of er I think, erm

I think, and I think erm were used as a delaying tactic. Although

phrases like let’s say…, what do you call

it and how will I put it were found. Perhaps this final finding may support

claims that the teaching of chunks should concentrate on multifunctional

phrases which can be of maximum benefit and of maximum flexibility at C1.

Furthermore, chunks which appear to be lexically important but which additionally have a functional capacity could also be a feature for instruction since chunks offer

a degree of efficiency, relevance and familiarity which may help to develop

pragmatic competence (Schmitt 2000).

5 Conclusion

The

findings outlined here have various implications for language pedagogy and

success in learning English. Vocabulary used by the C1 learners stemmed mostly

from the first thousand words of the BNC. Being successful in speech seems to

advocate a fundamental need for students to learn these words. It may also

justify Nation’s (2001: 16) claim that such lexis should receive “considerable”

attention since words beyond K-2 do not yield great profit in terms of

occurrence. Pedagogy could therefore supplement learners in two ways:

· Firstly, as per Nation’s

advice, classroom time could be maximised by exposing students to more frequent

vocabulary.

·

Secondly, teachers and

successful language learners could impart their knowledge of language learning

strategies. These readily available tools for language learning may help

learners exploit their target language knowledge, they can extend learning in

and out of the classroom and they are themselves believed to be a sign of a

successful language learner (Griffiths 2004, Oxford 1994, Oxford & Nyikos

1989). Specific strategies related to guessing word meaning from context,

remembering words and using materials such as dictionaries and wordlists may

result in greater efficiency for teaching and learning low-frequency

vocabulary.

Another

implication relates to the treatment of vocabulary by learners. Since many

learners “rely far more on word-by-word processing” (Foster, Tonkyn &

Wigglesworth 2000: 356), pedagogy could make students more aware of the value

of learning vocabulary in chunks instead of on

an individual basis (Boers et al. 2006). Successful C1 students were able to

employ some lexical chunks in their speech. Not only did most of these chunks

employ lexis from the K-1 category, but they also assisted in the realisation

of some CEFR can-do statements and they may have given the assessor a

greater impression of fluency and proficiency. Introducing learners to chunks

used frequently by native speakers and successful learners in speech may allow

them to take full advantage of their positive effects. If attention is also

paid to the way in which chunks can be multifunctional, students once again could

apprehend and reach the full potential of their

English vocabulary.

With

regards exam performance, this study could offer C1 learners some valuable

advice. Although some students, teachers and indeed some assessors may

discourage and disapprove of hesitation, it was found that successful

candidates did still exercise delaying techniques. Er and erm

were amongst the most frequent words used; phrases such as I think and I

agree with you were also used to fill pauses. Although the CEFR places

importance on spontaneous and fluent speech at C1, candidates can still pass

and be successful despite some hesitation. With regards

to the occurrence of can-do descriptors, successful C1 learners

evidenced their productive abilities more frequently than interactive and

strategic criteria. It is the author’s experience that learners are taught not

to give one-word answers; it could also be suggested that practitioners should

go beyond this and provide students with relevant examples from learner or

native corpora as to how more detailed answers could

be achieved. For instance, students may assume that greater complexity

is needed to develop ideas. The data, however, demonstrated that productive

language often involved the use of simple contractions such as because

and so to connect ideas.

Finally, it

remains to be acknowledged that this study involved a

rather small corpus. Additional research with an increased corpus size

is needed. A comparison of C1 data with other levels in the CEFR is also

required so that speaking exam success at different stages can be examined and

then compared to identify areas of similarity and contrast. Such research could

also provide a platform for subsequent investigations which would reveal more

about exam performance for the benefit of teachers, researchers, course

developers and, of course, students.

References

Adolphs, Svenja (2008). Corpus and context: Investigating pragmatic

functions in spoken discourse. Amsterdam

Adolphs, Svenja & Norbert Schmitt

(2004). Vocabulary coverage according to spoken discourse context. In Paul

Bogaards & Batia Laufer (Eds.) (2004). Vocabulary in a second language:

Selection, acquisition, and testing. Amsterdam

Adolphs, Svenja & Ronald Carter (2013).

Spoken corpus linguistics: From monomodal

to multimodal. London

Alderson, J. Charles (2007). The CEFR and

the need for more research. In: The Modern Language Journal 91(4), 659-663.

Alptekin, Cem (2002). Towards intercultural

communicative competence in ELT. In: ELT journal 56(1), 57-64.

Anthony, Lawrence

Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey

Leech, Susan Conrad, & Edward Finegan (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. London

Boers, Frank, June Eyckmans, Jenny Kappel,

Helene Stengers & Murielle Demecheleer (2006). Formulaic sequences and

perceived oral proficiency: Putting a lexical approach to the test. In: Language

Teaching Research 10(3),

245-261.

British National Corpus (BNC) (2004):

British National Corpus: What is the BNC?

(http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/corpus/index.xml; 21.05.14).

Cambridge English Corpus (CEC) (2014): (http://www.cambridge.org/about-us/what-we-do/cambridge-english-corpus; 30.01.15).

Canagarajah, Suresh (2007). Lingua franca

English, multilingual communities, and language acquisition. In: The

Modern Language Journal 91,

923-939.

Carter, Ronald & Michael McCarthy

(2006) Cambridge Cambridge : Cambridge University

Chujo, Kiyomi (2004). Measuring vocabulary

levels of English textbooks and tests using a BNC lemmatised high frequency

word list. In: Language and Computers 51(1), 231-249.

Chung, Teresa Mihwa & Paul Nation

(2004). Identifying Technical Vocabulary. In: System 32(2), 251-263.

Clark, Herbert & Jean Fox Tree (2002).

Using ‘uh’ and ‘um’ in spontaneous speaking. In: Cognition 84(1),

73-111.

Cobb, Tom (2014). Compleat Lexical Tutor.

(http://www.lextutor.ca/; 21.05.14).

Cobb, Tom (n.d.): Why and how to use

frequency lists to learn words. (http://www.lextutor.ca/research/; 21.05.14).

Conrad, Susan (2000). Will Corpus

Linguistics Revolutionize Grammar Teaching in the 21st Century?*. In: Tesol

Quarterly 34(3),

548-560.

Cook, Vivian (1999). Going beyond the native

speaker in language teaching. In: TESOL quarterly 33(2), 185-209.

Cook, Vivian (2008). Second language

learning and language teaching. London

Coste, Daniel (2007). Contextualising uses

of the common European framework of reference for languages. In Report of

the intergovernmental Forum: The Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages (CEFR) and the development of language policies: challenges and

responsibilities (pp. 38-47).

Council of Europe

[CoE] (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning,

teaching, assessment. Cambridge : Cambridge University

Dornyei, Zoltan, & Peter Skehan (2003).

Individual Differences in Second Language Learning. In: Catherine Doughty &

Michael Long (Eds.) (2003). The Handbook

of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford

Ellis, Nick & Susan Sinclair (1996).

Working memory in the acquisition of vocabulary and syntax: Putting language in

good order. In: The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology: Section A 49(1), 234-250.

Ellis, Rod (2008). The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford :

Oxford University

Erman, Britt, & Beatrice Warren (2000).

The idiom principle and the open-choice principle. In: Text 20(1), 29–62.

Figueras, Neus (2012). The impact of the

CEFR. In: ELT Journal 66(4),

477-485.

Foster, Pauline (2001). Rules and routines:

A consideration of their role in the task-based language production of native

and non-native speakers. In Bygate, Martin, Peter Skehan, and Merrill Swain

(Eds.) (2001). Researching pedagogic

tasks: Second language learning, teaching, and testing. Harlow :

Longman. 75-93.

Foster, Pauline, Tonkyn, Alan, &

Wigglesworth, Gillian (2000). Measuring spoken language: A unit for all

reasons. In: Applied Linguistics 21(3),

354-375.

Francis, W.

Nelson and Kucera, Henry (1982). Frequency

analysis of English usage. Boston ,

MA

Fulcher, Glenn (2004). Deluded by

artifices? The common European framework and harmonization. In: Language

Assessment Quarterly: An International Journal 1(4), 253-266.

Gardner, Robert, & MacIntyre, Peter

(1992). A student's contributions to second language learning. Part I:

Cognitive variables. In: Language teaching 25(04),

211-220.

Granger, Sylvaine, Estelle Dagneaux, Fanny

Meunier & Magali Paquot (2009): International Corpus of Learner English.

(http://www.uclouvain.be/en-cecl-icle.html; 16.06.14)

House, Julianne (2003). English as a lingua

franca: A threat to multilingualism? In: Journal of sociolinguistics 7(4), 556-578.

Hulstijn, Jan (2007). The shaky ground

beneath the CEFR: Quantitative and qualitative dimensions of language

Proficiency1. In: The Modern Language Journal 91(4), 663-667.

Kachru, Braj (1992). World Englishes:

Approaches, issues and resources. In: Language teaching 25(01), 1-14.

Kramsch, Claire (2003). The privilege of

the non-native speaker. In: The Sociolinguistics of Foreign-Language

Classrooms: Contributions of the Native, the Near-native, and the Non-native

Speaker. 251-62.

Jones, Chris, Daniel Waller & Patrycja.

Golebiewska (2013). Defining successful spoken language at B2 level: findings

from a corpus of learner test data. In: The

European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL 29-46.

Laufer, Batia & Paul Nation (1995).

Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. In: Applied

linguistics 16(3),

307-322.

Leech, Geoffrey (2000). Grammars of Spoken

English: New Outcomes of Corpus‐Oriented Research. In: Language learning 50(4), 675-724.

Leech, Geoffrey, Paul Rayson & Andrew

Wilson (2001) Word Frequencies in Written

and Spoken English: Based on the British National Corpus. London

Lewis, Michael (1993). The Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching Publications.

Lewis, Michael (1997). Implementing the Lexical Approach. Hove: Language Teaching

Publications.

Little, David (2007).

“The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Perspectives on the

Making of Supranational Language Education Policy”. In: The Modern Language Journal. 91: 645.

McCarthy, Michael (1999). What Constitutes

a Basic Vocabulary for Spoken Communication? In: Studies in English Language and Literature 1, 233-249.

McCarthy, Michael (2006). Explorations in Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge : Cambridge

University

McCarthy, Michael & Ronald Carter

(1995). Spoken Grammar: What is it and How can we Teach it? In: ELT Journal 49(3), 207-218.

McCarthy, Michael & Ronald Carter

(2001). Ten criteria for a Spoken Grammar. In: Eli Hinkel and Sandra Fotos

(Eds.) (2002). New Perspectives on

Grammar Teaching in Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah ,

NJ : Lawrence

Nagy, William, Richard Anderson, Marlene

Schommer, Julian Scott, and Anne Stallman (1989). Morphological Families in the

Internal Lexicon. In: Technical

Report No. 450.

Nation, Paul (2001). Learning vocabulary

in another language. Cambridge : Cambridge University

Nation, Paul, & Waring, Robert (1997).

Vocabulary size, text coverage and word lists. In: Vocabulary: Description,

acquisition and pedagogy, 6-19.

North, Brian (2006): The Common European

Framework of Reference: Development, theoretical and practical issues.

(http://www.nationaalcongresengels.nl/cgi-bin/north-ede-wagingen%202007-paper.pdf;

30.01.15)

Norton, Bonny (1997). Language, identity,

and the ownership of English. In: Tesol Quarterly 31(3), 409-429.

O’Keefe, Anne, Michael McCarthy &

Ronald Carter (2007). From corpus to

classroom. Cambridge : Cambridge University

O’Sullivan, Barry, Cyril Weir & Nick

Saville (2002) Using Observation Checklists to Validate Speaking-test Tasks.

In: Language Testing 19(1), 33-56.

Phillipson, Robert (1992). Linguistic

imperialism: African perspectives. In: ELT

Journal 50(2),

160-167.

Piller, Ingrid (2002). Passing for a native

speaker: Identity and success in second language learning. In: Journal

of sociolinguistics 6(2), 179-208.

Prodromou, Luke (2008). English as a

lingua franca: A corpus-based analysis. London: Continuum.

QSR International (2012).

(http://www.qsrinternational.com/; 21.05.14)

Robinson, Peter (Ed.) (2002). Individual differences and

instructed language learning (Vol. 2). John Benjamins Publishing.

Rubin, Joan (1975). What the" good

language learner" can teach us. In: TESOL quarterly, 41-51.

Schmitt, Norbert (2000). Key concepts in

ELT. In: ELT journal 54(4),

400-401.

Schmitt, Norbert (Ed.) (2004). Formulaic

sequences: Acquisition, processing, and use (Vol. 9). Amsterdam

Scott, Michael (2014). WordSmith Tools. Liverpool : Lexical Analysis Software.

Skehan, Peter (1998). A cognitive

approach to language learning. Oxford : Oxford

University

Smith, Vicki, & Clark, Herbert (1993).

On the course of answering questions. In:

Journal of memory and language

32(1), 25-38.

Stern, Hans Heinrich (1983). Fundamental

Concepts of Language Teaching: Historical and Interdisciplinary Perspectives on

Applied Linguistic Research. Oxford

University

Timmis, Ivor (2002). Native-speaker Norms

and International English: A Classroom View. In: ELT Journal 56(3), 240-249.

VOICE (2013): Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English.

(https://www.univie.ac.at/voice/page/what_is_voice;

30.01.15).

Weir, Cyril (2005). Limitations of the

Common European Framework for developing comparable examinations and tests. In: Language

Testing 22(3),

281-300.

Widdowson, Henry George (1994). The

ownership of English. In: TESOL quarterly, 28(2),

377-389.

Willis, Dave (1990). The Lexical Syllabus. London

Wray, Alison (2000). Formulaic sequences in

second language teaching: Principle and practice. In: Applied

linguistics 21(4),

463-489.

Wray, Alison (2002). Formulaic language

and the lexicon. Cambridge : Cambridge University

Author:

Shelley Byrne

Associate lecturer

E-mail: sbyrne@uclan.ac.uk