Volume 5 (2014) Issue 1

Determining

the Best Pedagogical Practices for Diverse

Grammatical

Features

Andrew

Schenck and Wonkyung Choi (both Daejeon, South Korea)

Abstract

Past

research has emphasized the universality of grammar acquisition over

key differences, resulting in the development of a number of

one-size-fits-all approaches to grammar instruction. Because such

approaches fail to consider disparities of grammatical features, they

are often ineffective. Just as a doctor needs to diagnose an illness

and prescribe a suitable treatment, the teacher must evaluate a

grammatical feature and choose an appropriate instruction. To better

understand how this may be accomplished, highly disparate grammatical

features (the definite article and plural noun) were taught to adult

second language learners, using three different pedagogical

techniques: Explicit focus on meaning, explicit focus on form, and

implicit focus on form. Results suggest that the effectiveness of

these treatments depends upon characteristics of the grammatical

feature, the type of instruction utilized (implicit or explicit), and

the learner’s language proficiency. According to the results, an

empirical method to guide the content of grammar instruction is

proposed.

Keywords: Explicit

grammar instruction, implicit grammar instruction, semantic

complexity, morphosyntactic complexity, learner proficiency, focus on

form, focus on meaning

1

Introduction

Researchers have developed a number of different theories to explain the seemingly universal nature of grammar development (Cook, Newson & Ning 1988, Freidin 2014, McCarthy 2004, Montague 1970, White 2009). Chomsky (1975, 1981, 1986), for example, posited that there is an innate system of syntactic constraints called principles and parameters. Principles are thought to represent the universal elements found in all languages, while parameters represent “on / off switches” set on a language-specific basis (Mitchell & Myles 2004). While such syntactic theories increase the saliency of the acquisition process, they cannot holistically explain linguistic development. Concerning this issue, Pinker (1994: 105) explained that:

The principles and parameters of phrase structure specify only what kinds of ingredients may go into a phrase in what order. They do not spell out any particular phrase. Left to themselves, they would run amok and produce all kinds of mischief.

As

this statement implies, innate notions of grammar structure alone are

not sufficient to explain the formation of language. In addition to

aspects of syntax and morphology, language learners must be born with

innate notions such as place, agent, and patient, which are used to

further regulate linguistic structures and

imbue them with

meaning (Pinker 1994).

While

innate mechanisms controlling morphosyntactic and semantic aspects of

language construction are well known (Chomsky 2011, Costello & Shirai 2011; Helms-Park 2002, Mitchell & Myles 2004, Pinker

1994), they represent only one facet of language formation. Memory is

yet another essential element of the language construction process.

Research suggests that language use relies considerably on

information received from a lexical store, which resides in long-term

memory (Pinker 1991, Eberhard, Cutting & Bock 2005). The lexical

store may best be characterized as a 'mental dictionary' which holds

syntactic, morphological, and semantic information about words and

phrases. Realization of the importance of this type of long-term

memory has led cognitive theorists such as Chomsky (1995) to suggest

that it is a main component of the acquisition process (Gass &Selinker 2008, Mitchell & Myles 2004).

Short-term

memory, also referred to as 'working memory', is yet another

essential element of language construction. It temporarily stores

input that is to be parsed or, conversely, output that is being

constructed. As

posited by Baddeley (1990, 1999), the working memory is governed by a

central executive which is supported by a visuo-spatial sketchpad

and a phonological loop. The visuo-spatial sketchpad stores semantic

information while the phonological loop holds acoustic information

that must constantly be refreshed through articulation (either saying

or thinking the words) (Cook 2008).

2

Theoretical Framework

In

an attempt to integrate and explain essential components of the

language acquisition process, researchers have designed some holistic

theoretical frameworks (Hurford

1989, Levelt

1989, 1996, and 2001). Levelt (1989), for example, developed a

cognitive model explaining the formation of linguistic output (Figure

1). According to this model, a semantic representation of an

utterance is first developed by a cognitive conceptualizer. The

resulting semantic conceptualization is then programmed into language

by a grammatical encoder. Finally, the encoder works to combine and

modify elements of the lexicon so that a grammatically correct

representation of the semantic concept may be constructed (Bock 1986,

Pienemann 2005).

Figure

1: Model of an innate language construction device

As

Levelt’s (1989) linguistic device includes both semantic and

morphosyntactic elements of language construction, it provides a more

holistic view of the Second Language Acquisition (SLA) process. While

the conceptualizer implies the presence of semantic constraints such

as those hypothesized by Pinker (1994), the encoder implies

morphosyntactic constraints such as those hypothesized by Chomsky

(1975, 1981 and 1986). According to the model, elements of a word,

phrase, or sentence in working memory come from the lexicon and are

organized by the innate construction mechanism. If information cannot

be retrieved lexically, it must be cognitively generated. Such

cognitive production is more difficult than retrieval from a lexical

store, since the innate language construction device must be more

extensively utilized. Exhaustive utilization of the device, in turn,

may put burdens

on the working

memory that serve to limit performance. In addition to gaps within

the lexicon,

a more conscious

evaluation of linguistic output, referred to by Krashen (1981) as a

“monitor”, may increase demands on the innate construction

mechanism, thereby influencing linguistic functioning.

Since

the

inception of English

as a Second Language (ESL) instruction, the role of grammar in the

pedagogical process has been of central concern. Initially, students

learned grammar by translating texts

into and from English. While

this instructional method which is referred to as the

grammar-translation

method

allowed

students to understand written texts, it did not

encourage natural use of

the target language. As a result, learners had difficulty gaining

communicative competence (Celce-Murcia 1991, Huang 2010). To address

this issue, educators soon crafted and utilized a new pedagogical

technique. This method, known as the audio-lingual

method,

prompted

students to learn through a process of habit formation. Learners

listened and repeated sentences that contained grammatical features

and expressions. While this technique encouraged the

spoken

use of the target language, there was little natural communication.

As with the grammar-translation

method, students who learned through the audio-lingual method

continued having problems

with both oral and written forms of natural communication (Thornbury

1999: pp.

21).

Due

to shortcomings with prior instructional approaches that were

primarily grammar-based, a new pedagogical approach was developed

which downplayed the importance of grammar and emphasized learning

through natural communicative tasks. Unfortunately, educators soon

realized that learners who acquired a language via this approach

could communicate, but had significant problems utilizing correct

grammar to express themselves (Lightbown 1998, Lightbown 2000). This

shortcoming resulted in a resurgence of interest in grammar-based

instruction (De Jong 2005, Lightbown, Halter, White & Horst

2002). While modern research now suggests that some kind of grammar

emphasis is needed, there is still considerable controversy over how

this emphasis should be pedagogically facilitated (Han 2012, Norris & Ortega 2000, Spada & Tomita 2010).

In

essence, the failure to concretely determine an effective type of

language instruction reflects a broader issue that has plagued both

SLA research and ESL instruction. Just as models of language

acquisition have overstressed the 'universal' nature of morphosyntax,

methods of instruction have overemphasized a one-size-fits-all

paradigm for teaching grammar. In reality, different forms of

instruction are needed to accommodate the highly disparate

characteristics of syntactic and morphological features. Educators

cannot use the same type of instruction for

each grammatical feature and

expect an equally fruitful outcome. To determine what type of

instruction is needed, diverse characteristics of grammatical

features must be considered. As DeKeyser (2005) points out,

grammatical features may differ significantly in both morphosyntactic

and semantic complexity. This assertion is illustrated through

examination of grammatical features associated with the noun phrase.

Regular plural nouns, which use regular forms such as -s,

-ies, or –es

(e.g. cars,

libraries,

grasses),

are relatively simple morphologically as well as semantically (they

only contain the meaning 'plural'). Lexical plural nouns, in

contrast, which require a complete change of the singular noun (e.g.

children,

men,

teeth),

are morphologically more complex, since

they

have a larger

number of variants. The article has very few morphological variants

(a,

an,

the).

Unlike

the plural

nouns, however, it is semantically very complex, and may be used to

signify semantic concepts such as: unique objects in our world (e.g.

the

sun),

groups in society (e.g. the

homeless),

parts of a list (e.g. the

first thing is…),

superlatives (e.g. the

biggest, the best),

and things already mentioned in a story (e.g. A

man talked to the woman. The man said,

“Hi”)

(Celce-Murcia,

Larsen-Freeman & Williams 1983: pp.279).

As

grammatical features differ significantly, educators must learn to

facilitate acquisition by differentiating instruction. The

development of such an approach requires not only a comprehensive

understanding of the factors that influence acquisition, but a firm

knowledge of the pedagogical techniques that effectively utilize

these factors. While many of the causes influencing grammar

development have been established within a universal framework of

acquisition, the contemporary corpus of research has not clearly

established how manipulating these factors can enhance the learning

of different grammatical features (Spada & Tomita 2010). To

resolve this issue, Han (2012) has suggested that the following

elements of instruction be concomitantly considered:

- Variable characteristics of each grammatical feature (e.g. semantic and morphosyntactic)

- Type of instruction (e.g. explicit vs. implicit)

- The developmental level of the learner

The

simultaneous consideration of the above factors will help educators

determine what type of instruction should be used for each

grammatical feature, how instruction should be used, and at what time

it should be used. This type of comprehensive investigation is needed

before curricula and instruction can be engineered to bring about a

desired result. Thus, the current study was designed to holistically

examine three influences on grammar acquisition:

- semantically and morphosyntactically diverse characteristics of grammatical features,

- different types of instruction, and

- learners’ proficiency levels.

2

Method

2.1

Participants

For

this quasi-experimental study, three university

English-as-a-Foreign-Language classes were selected at a small

university in South Korea (N

= 47). Learners were distributed within the following proportions:

Group 1 (n

= 15), Group 2 (n

= 15), and Group 3 (n

= 17). While most of the students were South Korean, learners from

other countries were also represented: Chinese (n=

6), Mongolian (n

= 1), and Tajikistani (n

= 1). All learners ranged in age from 18 to 21 years.

2.2

Procedure

As

pointed out by Asselin (2002), grammar may represent both “the

conscious knowledge of language structures” and “the unconscious

knowledge of language that allows people to produce and comprehend

language” (Asselin 2002: 52). Consequently, both conscious and

unconscious forms of knowledge about grammatical features were

evaluated within this study. To examine the effects of grammar

instruction on the acquisition process, three grammatical features

associated with the noun phrase were chosen: the regular plural (e.g.

cars,

libraries,

grasses,

etc.), the lexical plural (e.g. children,

men,

etc.) and the definite article the.

These features were selected because their morphosyntactic and

semantic characteristics are highly disparate.

Before

treatments were given to the three groups, participants each took a

pretest. The pretest contained two fill-in-the-blank worksheets each

having 10-14 questions - the worksheets were obtained from

learnenglishfeelgood.com

-

to test conscious knowledge of correct article and plural usage.

Learners were given as much time as they needed to complete the

worksheets. As pointed out by Ellis (2005),

untimed exercises

such as these are better measures of conscious or explicit knowledge

than timed exercises. Following the measure of conscious knowledge,

learners were given two images and three minutes to write a paragraph

for each. This task was timed to obtain a better measure of natural

ability or implicit knowledge of each grammatical feature. Timing

the activity minimized the degree that students could consciously

correct errors, ensuring

the validity of the measure (Ellis 2005). To score each test section,

correct answers were divided by the total number of answers (or the

total number of required contexts for the natural writing task). For

the natural writing task, ratings of grammatical errors (missing or

incorrect forms of the target feature) for one of the groups were

compared to those of an additional native English-speaking rater to

assess reliability. The resulting Cronbach’s a

value of 85.4% suggested that the method of assessment was a reliable

measure of grammatical accuracy. After all

the pretests had been scored,

the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis

statistical formula was used to confirm that the distribution of

pretest scores did not significantly differ across groups. This

suggested that there was no significant difference between the groups

at the beginning of the study.

Following

the administration of the pretest, three treatments were randomly

assigned to three different groups. Each group received an initial

lecture using a PowerPoint with examples from the topics covered in

Appendix A. The PowerPoint and explanation, however, varied depending

upon the treatment:

- Group 1 received explicit treatment of semantic concepts (e.g., images and graphic organizers with explanation);

- Group 2 received implicit treatment of morphosyntactic features (e.g., sentence examples);

- Group 3 received explicit treatment of morphosyntactic features (e.g., sentence examples with explanation).

Following

the treatment, all learners received a handout so that they could

review and practice the concepts learned during the treatment (Table

1):

Group

1

|

Group

2

|

Group

3

|

Explicit

Focus on Meaning:

PowerPoint mini-lecture with images and semantic maps.

|

Implicit

Focus on Form:

PowerPoint mini-lecture with sentence examples.

|

Explicit

Focus on Form:

PowerPoint mini-lecture with explanation of grammatical forms

along with the same sentence examples presented to Group 2.

|

Handout:

The main topics of the semantic map are provided but the

information in the bubbles is blanked out. Learners must fill in

the bubbles and add their own bubbles. They must then orally make

sentence examples.

|

Handout:

Learners see the sentence examples presented in the mini-lecture.

They practice speaking the sentence examples. They are then

encouraged to make additional sentence examples by speaking.

|

Handout:

Learners see the sentence examples presented in the mini-lecture.

They circle all the grammatical features emphasized in the

lecture. They practice speaking the sentence examples and make

additional sentence examples.

|

Table 1: Summary of treatments for each group

Group

1 received an explicit focus on meaning. The teacher intentionally

drew attention to semantic aspects of the target features through

describing images and graphic organizers included

within a PowerPoint.

Following

the PowerPoint, learners

were given a handout with the images and bubbles only. Students had

to fill in the bubbles according to the images. They were then asked

to expand on the bubbles and make sentence examples, using the target

features.

The

second group received an implicit focus on form. Using

a PowerPoint, learners

were each shown sentence examples which contained the same target

features as those presented to Group 1. Sentences such as the

following were read to students (notice that the target features

parallel those presented to the semantic treatment group):

- I went to the airport last night to pick up my best friend. He just came home.

- Could you stop by the supermarket on your way home from work? I need some milk.

- I stopped at the store and bought a new shirt.

- I went to the movie theater to see a new movie, but it was closed.

- He gave me an apple.

- He gave me some apples.

Following

the PowerPoint, learners were given a handout containing the same

sentence examples. They were then asked to practice reading the

sentences out loud to each other and practice speaking, using

vocabulary and expressions from the sentences. No explicit

explanation or mention of the target grammar was included within this

treatment.

The

Group 3 was shown the same sentences in PowerPoint and handout as

Group 2. Group 3, however, received an

explicit grammar explanation. The

teacher explained aspects of syntax and morphology (sentence position

of the target feature and form) for each feature and then read the

same sentence examples as Group 2. Any semantic explanations were

avoided. Learners were then given the same sentences in a handout as

the implicit group. Group 3, however, had to circle and identify the

grammatical features in the handout. After correctly identifying the

target features, learners were asked to read the sentences out load

and to practice making their own sentences.

Following

the treatment, each group was directly given a posttest. The form of

the posttest was identical to that of the pretest, although different

worksheets and images were used (The worksheets were obtained from

learningenglishfeelgood.com).

Because of the high degree of variability in plural forms (due

primarily to lexical characteristics), five different plural forms

covered in the treatment were also tested within the posttest

assessment of conscious plural knowledge use (lives,

sheep,

mice,

houses,

and libraries).

It was thought that such coverage would more accurately assess the

influence of the treatment, since participants could not be expected

to use lexical forms they had never seen. After the posttest,

descriptive statistics revealing the degree of improvement were

calculated and graphically charted. Next, the significance of

statistical differences between pretest and posttest for the target

grammatical features were determined using a paired samples T-test.

Finally, improvement was compared to participants’ English

proficiency scores, which were obtained from a TOEFL-style test of

listening, speaking, reading, writing, and vocabulary skills. To

obtain a basic

estimate of

the influences of language proficiency, learner improvement scores

were further subdivided into two groups (high and low proficiency)

through using median values. While the proficiency assessment was a

useful tool within this study to examine basic relationships between

English proficiency and the effects of different types of grammar

instruction, future studies will need more precise measures and more

detailed differentiation of proficiency levels.

3

Results

and Discussion

3.1

Analysis

of Group Treatment

Results

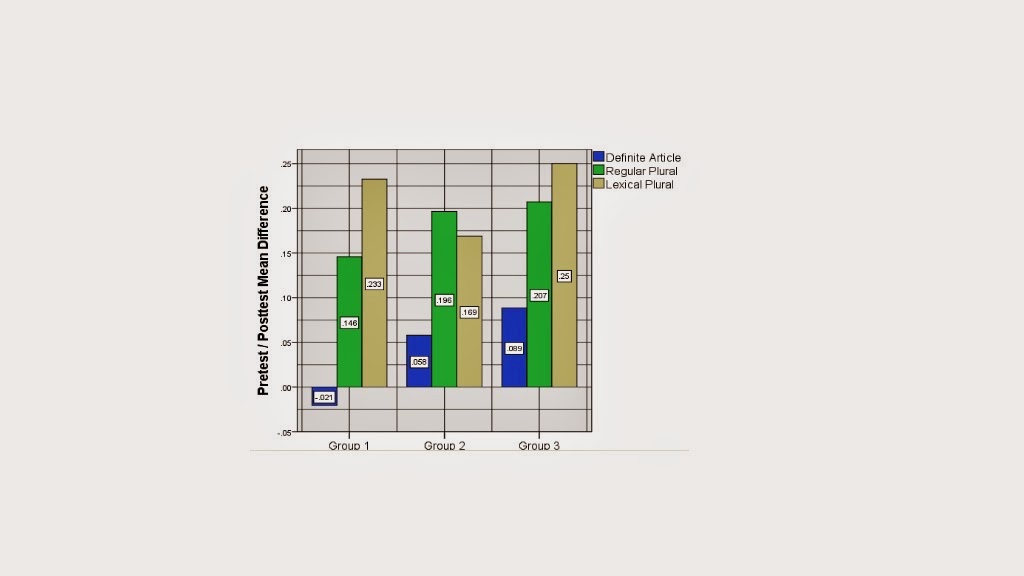

of the group treatments revealed different rates of conscious

learning for each target feature (Appendix B). Figure 2, which shows

the degree of improvement from pretest to posttest,

reveals that

Group 3 (the Explicit Focus-on-Form Group) had the highest gains for

all three features. The regular and lexical plural features increased

by 25% and 21%, respectively, on the posttest, while the definite

article rose by 9% only. Group 2, which received implicit grammar

instruction, revealed more moderate gains in conscious knowledge of

the regular plural, the lexical plural, and the definite article;

posttest scores increased by 20%, 17%, and 6%, respectively. Group 1,

which received the semantic treatment, yielded a 23% gain on the

lexical plural. This value was higher than that of Group 2, but lower

than that of Group 3. Mean differences for the regular plural and

definite articles

were

lowest within the semantic treatment group (15% and -2%,

respectively).

The

negative value

for the improvement

of the definite article suggests that the semantic treatment hindered

the participants’ abilities to identify the correct article.

Figure 2: Difference in the mean between pretest and posttest of conscious

knowledge

With

the exception of article use for Group 1, the participants' knowledge

of the usage of all grammatical features increased after each form of

treatment. The Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test indicated that an

improvement for aspects of the plural was significant for each group

(Table 2):

Definite

Article

|

Regular

Plural

|

Lexical

Plural

|

|

Group

1 Z

|

-.142b

|

-2.090b

|

-2.411b

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.887

|

.037

|

.016

|

Group

2 Z

|

-1.449b

|

-2.400b

|

-2.322b

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.147

|

.016

|

.020

|

Group

3 Z

|

-2.325b

|

-2.849b

|

-3.221b

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.020

|

.004

|

0

|

a. Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test . b. Based on negative ranks. d. The sum of negative ranks equals the sum of positive ranks.

Table

2: Significance of improvement of conscious knowledge of each

grammatical feature

While

the regular and lexical plural revealed significant gains for each

group, Group 3 had the most significant results, yielding respective

p

values of .004

and .001. Groups 1 and 2 did not show any significant gains for the

definite article. Group 3 (the Explicit Focus-on-Form Treatment

Group), however, did reveal significant gains.

Results

concerning the use of grammar on the natural language writing task

differed from those of conscious grammar knowledge (Appendix C,

Figure 3). Group 2, for example, which did not receive any explicit

grammar treatment, seemed to be negatively impacted by the treatment.

None of the grammatical features were used more proficiently on the

posttest. Group 3, which received treatment focusing on the form of

grammatical features in a sentence, revealed

significant improvement in use of articles and lexical plurals,

increasing by 19%

and 32%, respectively. The explicit semantic treatment of Group 1

appeared to bring about slight gains in use of the article (3%) and

regular plural features (10%):

Figure 3: Mean difference between the pretest and posttest of natural

language use

While

Group 1 revealed gains for both the regular plural and definite

article, neither of these gains was significant (Table 3). Only

improvements in use of the regular plural and definite article for

Group 3 were significant, revealing p

values of .012 and .042. Overall, increases in grammatical accuracy

for both groups with explicit instruction suggest that deliberate

focus on either semantic or morphosyntactic concepts encourages

learners to cognitively monitor and correct errors that occur in

natural language:

Definite

Article

|

Regular

Plural

|

Lexical

Plural

|

|

Group

1 Z

|

-.595b

|

-.271b

|

.000c

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.552

|

.786

|

1.000

|

Group

2 Z

|

-.981c

|

.000d

|

-1.342c

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.327

|

1.000

|

.180

|

Group

3 Z

|

-2.511b

|

-2.032c

|

-1.786b

|

Sig.

(2-tailed)

|

.012

|

.042

|

.074

|

a.

Wilcoxon

Signed Ranks Test. b. Based on negative ranks.

c.

Based on positive ranks. d. The sum of negative ranks equals the

sum of positive ranks.

Table

3: Significance of improvement of natural ability of each grammatical

feature

3.2

Analysis of Group Treatment and Language Proficiency

While

our analysis

of group achievement revealed important information about the

effectiveness of treatments, the

further

subdivision of improvement according to proficiency level yielded

even deeper insights:

Figure 4: Pretest / posttest mean difference of conscious knowledge based on

proficiency level.

Figure 4 suggests that the semantic treatment provided in Group 1 may be

ineffective only for learners of lower proficiency. Learners in the

higher proficiency level of Group 1 revealed gains that were slightly

higher than those of the high proficiency level of the Explicit

Focus-on-Form Treatment Group. The difference in achievement within

the high and low proficiency levels of the semantic group suggests

that learners must have a certain level of proficiency before they

can benefit from the explicit semantic treatment used within the

study. This view is supported by qualitative analysis. Students with

higher proficiency levels tend to correctly identify and expand upon

concepts included within the handout. Utilizing conceptions of

“unique things in our world” or “unique things in our society”,

for example, high proficiency learners were able to correctly

identify concepts such as the

earth,

the

poor,

the

sun,

and the

hungry,

and were able to generate new concepts such as the

stars,

the

land,

the

sea,

the

UN,

and the

weather.

Learners of lower proficiency, however, had difficulty completing the

handout and tended to just copy or mimic the expressions used within

the treatment. If such semantic treatment is provided to lower

proficiency groups, semantic complexity might need to be simplified

by utilizing just one, highly simplistic semantic concept. The

definite article, for example, could be explained as being simply

“unique”. Learners

can then begin with

a simple semantic concept and expand upon it as semantic information

in the lexicon grows.

In

contrast to the semantic group,

the morphosyntactic treatment group revealed more significant gains

in the low proficiency category for the definite article. This

phenomenon

may be explained by the largely bottom-up technique used within the

treatment. Unlike the top-down semantic explanations associated with

the definite article in Group 1, lower proficiency students of Group

3 received simple explanations about articles and their adjacent

nouns (e.g. “the airport, the movies”). Thus, learners of lower

proficiency could easily focus

their attention

on a singular concept (the adjacent noun) and could get the correct

answer

by copying and mimicking, rather than by advanced

semantic analysis.

The

high-proficiency

group

3 gained more on the lexical plural than their

low-proficiency counterparts. This phenomenon, as with the semantic

treatment of the

definite article in Group 1, may be a reflection of the complexity of

the grammatical feature. Lexical features have a large number of

variants. Thus, higher-proficiency-level learners may benefit more

from the infusion of lexical variants than their lower-proficiency

counterparts. As for the regular plural, achievement was

fairly consistent for each group. Lower proficiency groups achieved

more, while the higher proficiency groups achieved less.

This consistency

suggests that each type of treatment used within the study had

similar benefits for this feature. This phenomenon may be

a reflection of

the morphosyntactic and semantic simplicity of the regular plural.

Learners may be able to understand the feature without lengthy,

explicit explanations or extensive grammar exercises, making

pedagogical intervention less necessary.

The

comparison of proficiency levels and natural use of grammar also

yielded valuable insight (Figure 5). As with measures of conscious

knowledge for Group 1, the semantic treatment for the definite

article appeared to adversely influence the lower proficiency

learners, while it positively influenced high proficiency learners.

Low proficiency learners showed a mean gain of -2.6%, while the high

proficiency group had a mean gain of 7.5%. Also similar to measures

of conscious knowledge, the morphosyntactic-treatment Group 3

revealed larger gains in natural use of the definite article at the

lower proficiency level. Learners at the lower proficiency level, for

example, showed a 27% increase in article use in writing, which

was double that of

the high proficiency level (11%). In Group 1, the low proficiency

group revealed a large gain in the correct use of the regular plural

(22%). As for the lexical plural, the high proficiency groups 1 and 3

both showed mean increases (14% and 43%, respectively). Only the

low-proficiency learners of Group 3 had a mean gain for the plural

lexical feature (21%). While learners in the explicit-treatment

groups 1 and 3 both showed improvements in natural language ability,

the implicit-treatment group 2 showed no improvement. Implicit

learners actually had more problems with accuracy on the posttest

writing task.

Figure 5: Pretest / posttest mean difference of natural language use based

on proficiency level.

The

mean gains or losses for different grammatical features on the

writing task suggest that the effectiveness of treatments on natural

language accuracy will vary according to characteristics of the

grammatical feature, the type of grammar instruction (implicit vs.

explicit), and the learner’s proficiency level. Overall, explicit

rather than implicit instruction appears to help learners to better

monitor and correct natural language when complexity of the explicit

instruction is commensurate with the leaner’s proficiency level.

Low proficiency learners appear to benefit from explicit treatments

that include more simplistic semantic or morphosyntactic concepts.

The regular plural, for example, may have improved for the lower

proficiency learners of semantic-treatment group 1 because the

feature has a singular semantic concept ('plural') which can easily

be understood and consciously focused upon while writing. Unlike

their lower-level counterparts,

advanced proficiency learners may benefit more from explicit

instruction with more semantic (e.g. the definite article) or

morphosyntactic complexity (e.g. features with several lexical

variants such as the lexical plural or the

past irregular verb). This is suggested by improvements on more

complex features in the higher proficiency levels of Group 1 and

Group 3 (Figure 5). Higher proficiency levels may have a highly

developed lexicon and proficiency which allows them to concentrate on

the semantic and morphosyntactic complexity of some grammatical

features.

Through

the analysis

of natural language performance, it becomes clear that if more highly

complex features are to be taught to low proficiency learners, they

should be simplified. By teaching the concept of unique

or only

1,

for example, learners can gain a vague notion of the definite

article’s more complex semantic meaning. As proficiency increases,

explicit semantic instruction covering more precise contexts of the

definite article may be utilized. Like semantic aspects of grammar,

highly complex morphosyntactic elements (e.g. highly lexical

grammatical features) should be explicitly covered at higher levels

of proficiency. If learners are proficient in English, they have a

more highly developed lexicon that can be used to interpret complex

concepts explicitly covered. The more highly developed lexicon

reduces the load of semantically and morphosyntactically complex

explicit instruction on working memory, ensuring that learners are

able to monitor and improve their natural language performance.

Within future research, more detailed measures of the interaction

between instructional complexity and learner proficiency will be

needed to improve pedagogical techniques and curricular designs that

emphasize grammar.

4

Conclusion

Results

obtained from measures of conscious knowledge suggest that both

explicit and implicit forms of instruction help the learner to

understand grammatical features. As learners have a lot of time to

complete measures of conscious knowledge, they can carefully consider

various elements of sample sentences they receive, including

characteristics associated with target features. Like students who

receive explicit instruction, learners who are engaged with implicit

tasks have the time necessary to construe meaning from the multitude

of semantic and morphosyntactic cues they view within instructional

input.

Unlike

measures of conscious knowledge, those of natural language ability

suggest that only explicit forms of instruction are effective.

Because learners who receive implicit instruction do not have a lot

of time to process the morphosyntactic and semantic elements they

encounter, they may fail to cognitively monitor and correct their

errors. Learners who receive explicit instruction, in contrast, have

a narrower scope to contemplate, which decreases burdens on internal

cognitive monitors designed to correct speech errors. Thus, learners

who have received explicit instruction

appear able

to correct errors more quickly and easily in natural language tasks

such as writing.

In

essence, the influences of implicit and explicit treatments on

natural language are a manifestation of cognitive processes which are

associated with an innate language construction device. The

ineffectiveness of implicit instruction suggests that cognitive

monitors of natural language errors are being distracted by other

contextual factors within the input, while mixed results of explicit

instruction seem to imply that cognitive monitors can only work when

the semantic and / or morphosyntactic information being emphasized is

commensurate with the learner’s proficiency level. Learners of low

proficiency who have a rudimentary understanding of basic semantic

concepts need images or graphic organizers that are semantically

simple. Therefore, explicit semantic instruction of the regular

plural, which has little semantic complexity, is appropriate at this

stage. Explicit semantic instruction of the definite article is only

appropriate at this level if semantic explanations are oversimplified

(e.g. emphasis of a singular concept

such as the definite article’s meaning of 'uniqueness'). After

learners have stored basic

semantic concepts within their lexicon, they can benefit from more

holistic explanations of meaning. As with explicit explanations of

semantic characteristics, explicit forms of morphosyntactic

instruction should be used to emphasize simple, more regular

grammatical features at first. Morphosyntactically or lexically

variable grammatical features may then be explicitly emphasized as

the proficiency of a learner grows.

Results

of the study suggest that explicit grammar instruction must be

tailored to both characteristics of the grammatical feature and

proficiency of the individual learner. The following chart

illustrates how this may be done (Table 4):

Proficiency

Level

|

Semantic

Concepts for Explicit Presentation

(Top-down

/ Focus on Meaning)

|

Morphosyntactic

Forms for Explicit Presentation

(Bottom-up

/ Focus on Form)

|

Difficulty

Level of Explicit Instruction

(Load

on Working Memory)

|

Low

|

plural

|

-s

|

1+

1 = 2

|

unique

|

the

|

1+

1 = 2

|

|

plural

|

-s,

-es

|

1

+ 2 = 3

|

|

Medium

|

plural

|

-s,

-es, -ies

|

1+

3 = 4

|

unique

things in our situation / unique things in our neighborhood /

unique things in our city / parts of a list

|

the

|

4

+ 1 = 5

|

|

plural

|

teeth,

feet, children, men, women

|

1

+ 5 = 6

|

|

High

|

plural

|

-s,

-es, -ies, teeth, feet, children

|

1+

6 = 7

|

unique

things in our world / unique things in our society / unique

situation / unique in our neighborhood / unique things in our city

/ elements of a list

|

the

|

6

+ 1 = 7

|

|

generic

things / unique things in our world / unique things in our society

/ unique situation / unique in our neighborhood / unique things in

our city

|

a,

an, the

|

6

+ 3 = 9

|

Table

4: Determining the difficulty level and appropriateness of explicit

grammar instruction

Table

4 reveals how the content of explicit grammar lessons may be designed

and evaluated for difficulty. As revealed in the table, semantic and

morphosyntactic concepts can be carefully tallied and added to get a

score for overall difficulty level. Because this technique considers

both grammatical characteristics of a target feature and cognitive

levels of proficiency, the explicit instructional concepts and

techniques are tailored to the learner’s level of interlanguage

development. While useful, Table 4 remains only a rudimentary guide

to the structure of explicit instruction. More study of the

influences of explicit instruction on learners of different

proficiency levels is needed to increase the efficacy of such

curricular guidelines.

In

the past, approaches to language instruction applied only one general

principle to enact change. As suggested by

the data within this

study, however, instruction requires a multifaceted approach which

has been designed according to characteristics of a grammatical

feature and the cognitive level of a learner’s development. The

grammar-translation, audiolingual, and communicative methods were all

ultimately doomed to fail because they were not synergistically

combined to accommodate learner needs. In the future, the strengths

of each approach should be integrated to increase their

effectiveness. When a new integrated curricular framework for grammar

is designed, the grammar-translation approach may be used to

emphasize form and meaning; the audiolingual approach may be utilized

to emphasize form and phonological characteristics; and the

communicative approach may be used to emphasize semantic concepts,

such as those which are linked to sociolinguistic contexts. Using

this type of framework, instruction of highly variable lexical

features such as the plural noun or the irregular past can be

enhanced through

a more extensive

use of the grammar-translation or audiolingual methods. Instruction

of semantically complex features such as the definite article can be

improved through more communicative techniques that integrate images

and videos from various sociolinguistic contexts. In essence, each

pedagogical approach has a role in the instructional process.

Researchers and educators must therefore develop a multifaceted

framework that harnesses the influences of grammatical acquisition by

utilizing the strengths of each teaching strategy. This will help to

increase the efficacy of second or foreign language instruction.

Appendixes

Appendix

I

Concepts

Covered with Definite Article (8 Concepts)

- Unique things in our world: the earth, the moon, the sun, the sky

- Unique things in our society: the homeless, the hungry, the poor

- Unique things in our neighborhood or city: the airport, the supermarket, the store, the movie theater

- Unique things in our situation: the cup of coffee on the counter, the bathroom in our dormitory, the sofa, the stove, the swimming pool outside my house

- Unique things in my life: the best book I have read, the greatest day of my life, the worst day of my life

- Unique parts of a list: the first thing is, the second thing is, the third thing is

- Unique parts of a process: the beginning, the middle, the end;

- Unique elements in a story: the man, the woman

Concepts

Covered with Plural (14 Concepts: 7 Lexical Plurals / 7 Regular

Plurals)

- Apples

- Women

- Sheep

- Mice

- Libraries

- Furniture

- Feet

- Fish

- Toys

- Children

- Pens

- Lives

- Parents

- Houses

Appendix

II

- Group NumberDefinite Article PretestDefinite Article PosttestRegular Plural PretestRegular Plural PosttestLexical Plural PretestLexical Plural Posttest1Mean.7857.7800.7857.9222.7024.9333N151514151415Std. Deviation.13766.16562.19258.13897.25469.148402Mean.7667.8267.6833.8778.5333.7000N151515151515Std. Deviation.16525.11629.27495.13313.35187.356073Mean.7437.8294.7059.9118.6275.8824N171717171717Std. Deviation.18739.13117.25365.10404.20858.19995TotalMean.7644.8128.7228.9043.6196.8404N474746474647Std. Deviation.16310.13771.24283.12407.27814.26285

Table

II / 1: Pretest / posttest scores for tests of conscious knowledge

Appendix

III

- Group NumberDefinite Article PretestDefinite Article PosttestRegular Plural PretestRegular Plural PosttestLexical Plural PretestLexical Plural Posttest1Mean.7348.7697.8556.9107.9091.8333N151512141112Std. Deviation.20115.27139.30462.19738.21556.325672Mean.6286.5794.8909.8056.8929.7037N1414119149Std. Deviation.33304.34367.30151.34861.28947.454743Mean.6460.8375.8867.7424.5577.8846N171615111313Std. Deviation.23717.17396.27997.38811.50160.29957TotalMean.6696.7346.8781.8284.7829.8186N464538343834Std. Deviation.25842.28388.28646.30973.38824.35145

Table

III / 1: Pretest/posttest scores for tests of natural language

ability

References

Asselin,

M. (2002). Teaching grammar. Teacher

Librarian, 29(5),

52-53.

Baddeley,

A.D. (1990). Human

memory: Theory and practice.

Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Baddeley,

A.D. (1999). Essentials

of human memory.

East Sussex: Psychology Press Ltd.

Bock,

J. K. (1986). Meaning, sound, and syntax: Lexical priming in sentence

production. Journal

of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 12(4),

575.

Celce-Murcia,

M. (ed.) (1991). Teaching

English as a second or foreign language (2nd

ed.).

Boston,

MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Celce-Murcia,

M., Larsen-Freeman, D. & Williams, H. A. (1983). The

grammar book: An ESL/EFL teacher's course.

Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Cook,

V. (2008). Second

language learning and language teaching.

(4th ed.). Cary, NC: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky,

N. (1975). The

logical structure of linguistic theory.

New York, NY: Plenum.

Chomsky,

N. (1981). Lectures

on government and binding.

Dordrecht, Netherlands: Foris.

Chomsky,

N. (1986). Knowledge

of language: Its nature, origin, and use.

New York, NY: Praeger.

Chomsky,

N. (1995). The

minimalist program.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky,

N. (2011). Language and other cognitive systems. What is Special

About Language?. Language

Learning and Development, 7(4),

263-278.

Cook,

V. J., Newson, M., & Ning, C. (1988). Chomsky's

universal grammar: an introduction.

Oxford, England: Blackwell.

Costello,

W., & Shirai, Y. (2011). The aspect hypothesis, defective tense,

and obligatory contexts: Comments on Haznedar, 2007. Second

Language Research, 27(4),

467-480.

De

Jong, N. (2005). Can second language grammar be learned through

listening?: An experimental study. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2),

205-234.

DeKeyser,

R. (2005). What makes learning second language grammar difficult? A

review of issues. Language

Learning, 55(1),

1-25.

Eberhard,

K., Cutting, J., & Bock, K. (2005). Making syntax of sense:

Number agreement in sentence production. Psychological

Review, 112(3),

531-559.

Ellis,

R. (2005). Measuring implicit and explicit knowledge of a second

language: A psychometric study. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2),

141-172.

Freidin,

R. (2014). Recursion in generative grammar. In Language

and Recursion (pp.

139-147). New York, NY: Springer.

Gass,

S.M., & Selinker, L. (2008). Second

language acquisition: An introductory course

(3rd

ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Han,

Z.H. (2012) Second

language Acquisition.

(Ed. J. Banks) Encyclopedia of diversity in education. doi:

10.4135/9781452218533.

Helms-Park,

R. (2002). The need to draw second language learners’ attention to

the semantic boundaries of syntactically relevant verb classes.

Canadian

Modern Language Review, 58(4),

576-598.

Huang,

J. (2010). Grammar instruction for adult English language learners: A

task-based learning framework. MPAEA

Journal of Adult Education, 39(1),

29-37.

Hurford,

J. R. (1989). Biological evolution of the Saussurean sign as a

component of the language acquisition device. Lingua, 77(2),

187-222.

Krashen,

S.D. (1981). Second

language acquisition and second language learning.

Oxford: Pergamon.

Levelt,

W.J.M. (1989). Speaking:

From intention to articulation.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levelt,

W. J. (1996). A theory of lexical access in speech production. In

Proceedings

of the 16th conference on Computational linguistics-Volume 1 (pp.

3-3). Association for Computational Linguistics.

Levelt,

W. J. (2001). Spoken word production: A theory of lexical access.

Proceedings

of the National Academy of Sciences, 98(23),

13464-13471.

Lightbown,

P. (1998). The importance of timing in focus on form. In C. Doughty & J. Williams (Eds.), Focus

on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition

(pp. 177-196). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Lightbown,

P.M. (2000). Anniversary article: Classroom SLA research and second

language teaching. Applied

Linguistics, 21(4),

431-462.

Lightbown,

P.M., Halter, R.H., White, J.L., & Horst, M. (2002).

Comprehension-based learning: The limits of 'do it yourself'. The

Canadian Modern Language Review, 58(3),

427-464.

McCarthy,

J.J. (2004). Optimality

theory in phonology.

Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Mitchell,

R., & Myles, F. (2004). Second

language learning theories

(2nd

ed.). London, UK: Hodder Arnold.

Montague,

R. (1970). Universal grammar. Theoria, 36(3),

373-398.

Norris,

J.M. & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A

research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language

Learning, 50(3),

417-528.

Pienemann,

M. (2005). Cross-linguistic

aspects of processability theory.

Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Pinker,

S. (1991). Rules of language. Science,

253(5019),

530.

Pinker,

S. (1994). The

language instinct: How the mind creates language.

New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Spada,

N., & Tomita, Y. (2010). Interactions between type of instruction

and type of language feature: A meta-analysis. Language

Learning, 60(2),

263-308. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2010.00562.x

Thornbury,

S. (1999). How

to teach grammar.

Essex, England: Pearson Education Limited.

White,

L. (2009). Second

language acquisition and universal grammar.

New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Authors:

Andrew

Schenck

Assistant Professor

Pai Chai University

Ju Si-Gyeong College

Liberal Arts Education Center (LAEC)

Pai Chai University

Ju Si-Gyeong College

Liberal Arts Education Center (LAEC)

Daejeon,

South Korea

E-Mail: Schenck@hotmail.com

E-Mail: Schenck@hotmail.com

Wonkyung

Choi

Associate

Professor

Pai Chai University

Ju Si-Gyeong College

Liberal Arts Education Center (LAEC)

Ju Si-Gyeong College

Liberal Arts Education Center (LAEC)

Daejeon, South Korea

E-Mail:

wkchoi@pcu.ac.kr