Volume 7 (2016) Issue 2

The Status of Peer Review in Applied Linguistics Research

K. James Hartshorn (Provo (Utah), USA)

Abstract

The peer review process is vital to the evaluation of scholarship in every discipline including Applied Linguistics and its related fields. Yet, in many disciplines, the landscape is shifting as longstanding concerns with peer review resurface in a world awash with changing social expectations and advances in technology that provide innovations in the evaluation and dissemination of scholarship. While scholars in many fields are abandoning traditional methods of review, where do scholars in the fields of Applied Linguistics stand amid such change? The present study identifies the collective voice of the field, regarding peer review as currently practiced in contrast to alternatives gaining traction in other fields. Data elicited from journal editors, editorial board members, and reviewers were analyzed to reveal perceptions of the peer review process, the various roles of reviewers, different methods of review as well as numerous strengths, limitations, and suggestions for improvement that could benefit practice.

Keywords: Peer review, scholarship, applied linguistics, online publishing

1 Introduction

The peer review process is central to the evaluation and dissemination of accepted scholarship in every discipline including Applied Linguistics and its related fields. Though various forms of peer review have been around for centuries, we see assertions of entrenched problems. Horton (2000) represented the views of some scholars when he claimed,

we know that the system of peer review is biased, unjust, unaccountable, incomplete, easily fixed, often insulting, usually ignorant, occasionally foolish, and frequently wrong. (Horton 2000: 148)

Though such indictments of peer review are not new, some of the challenges unique to the twenty-first century and the innovations being used to address them are unprecedented. For example, Gould (2013) warns,

We stand at a tipping point. All of our experience with scholarly review and publishing is under assault. (Gould 2013: 1)

Amid the scramble of well-established journals to adapt to ever-changing delivery systems, Gould claims that peer review “faces a challenge to its very existence” and that without appropriate corrective action, “we may find ourselves in a world largely without any standards for publishing.” (Gould 2013: 1)

In addition to longstanding concerns about review processes, recent changes in technology and emerging types of publication have evolved so rapidly that it is vital that we carefully examine the current state of peer review and its implications for the future. For example, we know little about the extent to which those closest to the review process in Applied Linguistics and its related fields share concerns about the status quo. Nor is it clear whether the custodians of this scholarship are aware of emerging forms of evaluation, innovations in dissemination, or growing concerns regarding review in a world clamoring for more social justice, equity, accountability, and transparency. Thus, the purpose of this study is to carefully examine perceptions of peer review in the field of Applied Linguistics with the aim of identifying consensus regarding emerging trends as well as potential strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement.

2 Review of Literature

Simply defined, peer review is the process by which a scholar's work is evaluated by expert peers to determine its suitability for publication in an academic journal. An early method of evaluating a manuscript was editorial review, where decisions rested solely with the editor. It was efficient but prone to bias. Though some of today’s processes for review have been around for centuries, systems used by various journals became more refined and widespread in the twentieth century (Shamoo & Resnik 2015). These systems usually involved some form of blinding to preserve anonymity. The most common method of peer review is the single-blind method, where the author is known to the reviewers, but the reviewers are not known to the author (Ware 2008). Other types of review include the double-blind method, where neither reviewers nor authors know theothers’ identities. Less common is the triple-blind method, where editors do not know the author’s identity in the initial stages of the review process (e.g. Gould, 2013).

2.1 Benefits of Peer Review

Peer review has been perpetuated because of its apparent benefits. For example, Shatz (2004) notes “Peer review serves the academic community by controlling the flow of ideas and enhancing the quality of scholarly work” (Shatz 2004: 30). He also observes:

It motivates scholars to produce their best, provides feedback that substantially improves work which is submitted, and enables scholars to identify products they will find worth reading. (Shatz 2004: 30)

Similarly, Ware (2008) suggests that all the key stakeholders benefit from peer review. For example, “editors are supported in their decisions by the views of experts,” “authors benefit from the assistance offered by reviewers,” “readers benefit because of the filter that peer review provides,” and “even reviewers…benefit” with professional development and early access to research (Ware 2008: 12).

2.2 Challenges Associated with Peer Review

Despite these long-held benefits, criticisms of peer review have emerged, based on years of experience and empirical study. For example, Smith (2010) claims, “we have no convincing evidence of its benefits but a lot of evidence of its flaws” (Smith 2010: 1). Many scholars agree with such sentiments. For instance, in a presentation to the American Psychological Association, Schmelk in (cited in Shatz, 2004) summarized studies suggesting that peer review is prone to harmful bias and incompetence, it lacks scientific evidence for its benefits, the process is slow and costly, it produces many papers with appalling flaws, it often misses misconduct from authors while allowing unscrupulous reviewers to steal ideas or to slow or stop progress toward publication, it is subject to may political pressures, and in the guise of anonymity, it often produces reviews that are caustic, arrogant, or irresponsible.

Though many concerns about the peer review process have existed since the beginnings of peer review itself, there are new complexities in the twenty-first century that might be added to the list. For example, in an attempt to adjust for problems associated with bias, incompetence, and misconduct (e.g. Bohannon 2013, Bosch 2014, Clair 2014, Macdonald 2015, Resnik, Gutierrez-Ford & Peddada 2008, Rothwell & Martyn 2000, Thurner & Hanel 2011, Triggle & Triggle 2007, Tsang 2013), some scholars have advocated replacing blind reviews with a more transparent practice. Some scholars agree with editors such as Smith (2006, who recommended that we “open up the whole process and conduct it in real time on the web.” “Peer review,” he continues, “would then be transformed from a black box into an open scientific discourse” (Smith 2006: 181).

2.3 The Effects of Open Review

Interpreting the actual overall benefits of open review, however, may be difficult. Just a few examples may suffice so as to support this point. Jadad, Moore, Carroll & Jenkins (1996) found that blinding produced greater consistency compared to open reviews. However, Van Rooyen, Godlee, Evans, Black & Smith (1999) found no difference in an open review format in terms of review quality, recommendations for publication, or the time required to complete the reviews. However, they did observe that reviewers are less willing to review in an open format. This lack of willingness to participate in open reviews has also been observed by others (e.g. Ware 2008). On the other hand, in a study conducted by Walsh, Rooney, Appleby & Wilkinson (2000), it was found that signed reviews were of greater quality, more polite, and more likely to recommend publication though they took longer to complete. Some of these findings seem consistent with those of Kowalczuk, Dudbridge, Nanda, Harriman & Moylan (2013), who found that open reviews were of greater overall quality, provided better feedback on methods, were more constructive and provided more evidence to substantiate reviewer claims:

While much more research may be needed to settle this question, the philosophical aspects of the debate seem at least as salient as the science (e.g. Groves 2010, Khan 2010). In the meantime, many journalsand scholars are adapting to the changing landscape. A number of newly launched journals such as GigaScience, PeerJ, eLife, and F1000Research (Walker & Rocha da Silver 2015) are using an open review procedure along with many other innovations to address long-standing problems associated with traditional peer review. Other existing journals continue to join the open-review bandwagon (e.g. Berardesca 2015, Groves & Loder 2014, Koonin, Landwber & Lopman 2013, Shanahan & Olsen 2014).

2.4 Preprint Servers and Quasi-Review

In addition to various forms of open and interactive review are preprint servers and quasi-reviews. Preprint servers such as ArXiv, Nature Precedings, Math Prepreints, andCogprints make manuscripts available after a quick check of minimal standards and credentials but without formal reviews. There also are open access venues with a “non-selective review process, which consider only the scientific quality” of a manuscript rather than its “importance” or “novelty” (Walker & Rocha da Silver 2015: 2). Because of suchdevelopments, the evaluation and dissemination of academic work in every field are awash in change. Rather than ignore these trends, we should confront, analyze, and seek to understand them and their relevance in our various contexts. Some adjustments may benefit processes associated with reviewing and sharing quality scholarship while othersmay undermine them.

2.5 Research Questions

Although different approaches to the evaluation of scholarship may be appropriate within different disciplines, there is a clear and present need for scholars within the fields of Applied Linguistics to contribute to the collective voice as the larger field confronts many old and some new challenges on the shifting landscape of peer review. Innovations or adjustments to peer review, if any, should be made by design rather than by default. Moreover, input from a variety of stakeholders needs to be considered in order for findings to be representative. Those closest to the review process will include editors, editorial board members, reviewers, and authors. Such roles, however, are far from exclusive. Invariably, editors also function as reviewers, and both editors and reviewers continue to function as authors. Thus, in an attempt to provide additional insight for such custodians of scholarship within the fields of Applied Linguistics, the following research questions were formed for editors, editorial board members, and reviewers:

1. How satisfied are scholars with the current peer review process?

2. Do peer review processes need to improve as online and self-publication proliferates?

3. What are the primary roles of the reviewer? Are some roles more important than others?

4. How do experts feel about various review methods and processes?

5. What are the strengths and weaknesses with current peer review processes?

6. What suggestions, if any, do scholars have for improving review processes?

Regardless of what the findings may indicate, the answers to such questions should be of great value at a time when many fields are reevaluating their approaches to the review process.

3 Method

3.1 Analyses

In order to answer the above research questions, a study was designed to elicit self-reported data from respondents with substantial experience as editors, editorial board members, and reviewers. Though critics may be leery of self-reported data over concerns that participants may not provide accurate responses, scholars such as Chan (2009: 326), assert that self-reporting is not only “justifiable” but “necessary” for particular constructs that might not be accessible any other way. The survey instrument was designed to elicit data from objective and open-ended items in order to present quantitative analyses along with respondent commentary.

3.2 Respondents

3.2.1 Identifying Respondents

The intent was to elicit responses from as many international editors, editorial board members, and reviewers in fields related to Applied Linguistics as possible. Potential respondents came from

- personal acquaintances of the author such as colleagues serving as editors, editorial board members, or reviewers,

- editors or board members well-known within the field, and

- editors, board members, and reviewers associated with relevant journals listed in online sources such as the Scopus-based portal, SC Imago Journal and Country Rank (Language and Linguistics, n.d.) and the Linguistic List (Browse Journals, n.d.).

With extensive overlap of scholars across multiple journals and multiple roles, the focus was on the individuals themselves more than the journals. Nevertheless, specific individuals were only targeted if they had a clear connection to Applied Linguistics and its related fields rather than being limited to narrow specializations in areas such as Psychology, Education or anthropological, historical, forensic, or evolutionary linguistics.

3.2.2 Response Rate

E-mail addresses were collected for editors, board members, and reviewers, where available. Ethics approval was obtained and the survey was constructed and piloted on a local level to identify areas for improvement. The refined instrument (see Appendix) was sent to 760 individuals, based on the best available contact information. The survey delivery software reported that the email was opened by 473 individuals and that the survey was started by 348 persons. Ultimately, 261 respondents completed the survey. This means that 55.2% of the total number of 473 individuals who had been contacted confirmed to have received the email.

3.2.3 Respondent Demographics

This study examined data from three types of respondents, including journal editors, those serving on editorial boards, and reviewers, all of whom were also authors. Since these rolls are not mutually exclusive, definitions were provided. For the purposes of this study, all editors and section editors were considered to be editors. Board members were defined as those serving on an editorial board but not in the capacity of an editor. Reviewers were defined as those who review for journals but who do not serve in the capacity of editor or board member.

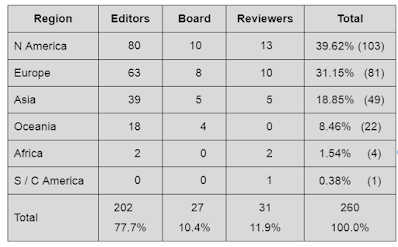

This section identifies relevant similarities and differences among journal editors, board members, and reviewers. Table 1 shows that more than three quarters of the respondents serve as editors and that board members and reviewers made up just over a tenth of the respondents each. The table also indicates one of six broad regions inwhich these scholars do most of their work. While most respondents work in North America and Europe, just over a quarter work in Asia and Oceania. Less than 2% of the respondents reported working in other locations:

Table 1: Regions in which Respondents Work

Table 2 presents the respondents’ years of service in the roles of editor, member of an editorial board, reviewer, and author. The table includes the mean number of years respondents have served in each role (M) along with standard deviations (SD). There were some notable differences among those who were defined by these various roles. For example, there was a statistically significant difference in the number of years of experience as a reviewer across roles (F(2,245)=8.992, p<.001). As might be expected, editors had more experience reviewing than those defined only as reviewers (p<.001, d= 1.074). Board members also had more years of service compared with those defined only as reviewers (p=.012, d=.933). Similarly, differences were observed across roles in number of years as an author (F(2,242)=8.785, p<.001). Those defined as reviewers had significantly fewer years as an author compared to editors, (p<.001, d=1.056), and fewer years compared to board members (p=.014, d=1.030):

Table 2: Mean Years of Service within Each Roll

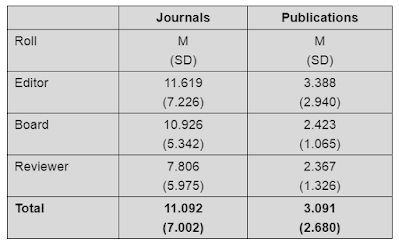

Additional demographic information provided in Table 3 presents the total mean number of journals that respondents have worked with as an editor, board member, or reviewer. It also includes the respondents’ average number of publications annually. The mean number of journals with whom respondents worked differed significantly (F(2,257)=4.087, p=.018). For example, reviewers reported working with fewer journals compared with editors (p=.013, d=.575). However, there was no meaningful difference among respondents with varied roles in terms of the mean number of annual publications (F(2,251)=2.466, p=.087):

Table 3: Mean Number of Journals and Annual Publications

4 Results

4.1 Examining the Status Quo

The first research question addressed the current level of satisfaction with peer review. Using a six-point scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6), participants responded to the statement I am satisfied with the current peer review process. The mean response fell between somewhat disagree and somewhat agree (N=259, M=3.842, SD=1.152), suggesting weak support for the status quo as well as some dissatisfaction. Using the same scale, the second research question elicited responses for the statement: Review processes need to improve as online, self-publication increases. The mean response for this item was between somewhat agree and agree (N=252, M=4.421, SD=1.163), suggesting apprehension over emerging trends for evaluating and disseminating scholarship.

4.2 The Roles of the Reviewer

The third research question addressed the relative importance of the 12 responsibilities of the reviewer presented in the survey. Though there were no significant differences between editors, board members, or reviewers for any of the 12 responsibilities, statistically significant differences were observed in terms of their relative importance (F(11,3103)=127.567, p<.001). Table 4 presents the number of respondents for each responsibility (N), the mean score (M), and the standard deviation (SD). It also shows six statistically different homogeneous subsets. Responsibilities are statistically different from one another where there are no overlapping asterisks (*) across subsets:

Table 4: Responsibilities of the Reviewer

These results show that respondents assigned a varying level of importance to these responsibilities. Those perceived to be the most important for the reviewer include devaluating and providing feedback on the methods and conclusions in a manuscript. This was followed by the findings, the review of literature, and the application of theory. While these priorities relate to specific sections of the manuscript, the next areas of importance seem less distinct. These include addressing plagiarism and the general improvement of the manuscript. They also include the timeliness of the reviewer’s work. The next responsibilities focus on the key players who interact through the process: the reviewer who develops professionally by engaging in the process and the author who develops professionally through the mentoring of the reviewer. Though still considered relatively important, the final areas included the editorial functions of addressing grammar and formatting.

Respondents were also able to suggest responsibilities that were not included in the instrument. The most frequently added duty was the need for the reviewer to evaluate the originality of the work and its unique contribution to the field. Other responsibilities focused on the clarity of the work and the need to ensure that ethics guidelines were followed. It was also suggested that reviewers needed to evaluate the appropriateness of a manuscript for a specific journal and guide authors to more appropriate journals when necessary. Rather than limiting answers to what reviewers should do, other responses focused on how they should fulfill their responsibilities. One participant emphasized the necessity for reviewers to stay current with ongoing research and a number of participants included the need for reviewers to be “impartial,” “thorough,” “respectful,” and “constructive.”

4.3 Examining Review Methods

The fourth research question addressed the respondents’ relative support for various review methods. Again, no significant differences were observed between editors, board members, or reviewers, though there were statistically significant differences across the various types of review (F(6,1782)=154.012, p<.001). Table 5 presents the relative approval rating based on a six-point scale for the seven review types examined in this study. The double-blind review received the strongest approval and on average was evaluated between approve and strongly approve. A statistically significant difference with a large effect size was observed between the approval rating of the double-blind review and the next most popular review type, the triple-blind review, evaluated just above somewhat approve (p<.001, d=.948). The difference between the triple-blind review and the editorial review was also significant with a medium effect size, (p<.001, d=.537). Nevertheless, respondents were split between marginal levels of approval and opposition to the editorial review. The remaining review types garnered varying levels of opposition:

Table 5: Levels of Approval for Review Types

Comments from the strongest advocates of the double-blind review focused on the strengths of having at least a second or third reviewer to reduce bias, promote academic freedom, and equip editors with multiple perspectives. Some advocates focused on how this method effectively balances the need for fairness with efficiency, suggesting thatmore elaborate schemes could make the process more cumbersome and less effective. Much of the opposition to the double-blind review was focused on problems associated with anonymity though many acknowledged that reviewers often know the identity of the author and that the author often knows the identity of the reviewer, particularly among authors of notoriety working within specific areas of research.

The strongest proponents of the triple-blind review focused largely on the additional elements of fairness for the author by blinding the editor in the initial phases of the process. These respondents described it as “fairer,” “least biased,” and “more balanced.” While many of those least enthusiastic about this type of review acknowledged the potential for reducing more bias, they also raised a number of concerns. They described the triple-blind review as “too cumbersome,” “time-consuming,” “overkill,” “impractical,” and indicated that it would introduce “logistic difficulties” and “inefficiencies” into the review process. Some respondents emphasized the need for editors to be directly involved from the outset. In addition to safeguarding against plagiarism, this would allow editors to find reviewers best suited for a particular manuscript while preventing conflicts of interest. Another indicated that the triple-blind review would undermine the ability for editors to utilize “their knowledge of the context of each submission as well as that of the journal” as they make editorial decisions. Nevertheless, one editor who felt the need to promote the success of a journal admitted “sometimes publishing certain names will make a volume more noteworthy,” suggesting that the prominence of particular authors may influence some editorial decisions.

Many of the proponents of the editorial review focused on the need for editors to be able to sift through the many submissions at the outset of the broader review process and to reject those manuscripts that are unsuitable either because of fatal design flaws or a misalignment with the aims of the journal. This, of course, safeguards the time of the reviewer to focus on those manuscripts most likely to be publishable. Beyond this, however, some respondents believed that a pure editorial review might be an acceptable compromise to make publication timelier. Some suggested it might be acceptable only if manuscripts were of very high quality or the review process was extremely transparent. Others felt the appropriateness of only using an editorial reviewer would depend on the specific journal. For example, eight respondents (3%) specifically indicated that an editorial review could only be acceptable for “minor journals,” those of “lower impact,” or other non-scientific venues. Some respondents indicated that a pure editorial review introduces too much bias and may undermine the effectiveness of the process if the expertise of the editors is not well aligned with that of the author.

The remaining four types of review were met with varying levels of opposition as illustrated by the means in Table 5. In addition to this statistical analysis, some representative respondent comments are provided here to help contextualize these findings. The least unpopular of these was the open peer comment option, which generated very mild opposition. This included the immediate “publication” of articles in an electronic format to which interested experts could provide commentary and authors could make revisions based on feedback. Some respondents were strongly supportive with comments such as it would be “very efficient,” it would be a “useful way of obtaining ideas quickly,” and “it has the appeal of science as a living organism.” Another respondent indicated that this type of review “could be greatly beneficial with an active, engaged community of scholars.” However, many respondents raised concerns such as the expectation that open peer commentary would flood the field with poor quality research. Another problem was what one respondent described as “a logistical nightmare in terms of trying to cite different versions of an article” in a perpetual review process. Other challenges include the likelihood of non-expert commentaries, the prospect of conflicting reviewers, and the possibility of no experts being interested in providing the feedback needed to improve the manuscript. One respondent also suggested that this approach would undermine protections from embarrassment provided to authors whose work undergoes rigorous review. Despite these concerns, many respondents suggested that this might be a valuable way to garner feedback of one’s work within a prepublication phase or as a way to facilitate public debate of new ideas that might inform later publications.

The next type of review was the private open review where the identities of the reviewers and the author are know to each other but kept private (i.e. not shared publicly). This also generated mild opposition overall as shown in Table 5. The strongest advocates of this form of review focused on the benefits of fully disclosing the identities of all parties involved. Some respondents felt that this would ensure higher quality reviews and help prospective authors to better contextualize the comments. They also felt it might minimize overly harsh or condescending reviews from reviewers hiding behind anonymity. Nevertheless, other respondents were critical of this approach indicating that it could undermine the objectivity needed for quality review and result in greater superficiality. It might also be more humiliating, create awkward tensions, and increase personal resentments between authors and reviewers.

The next review type was the single-blind review, in which the identity of the author is known to the reviewer though the reviewer’s identity is not known to the author. This garnered moderate opposition as shown in Table 5 Many respondents acknowledged that, in effect, this is very common in practice simply because authors are often recognized by the work they do. Some respondents indicated that the appropriateness of the approach could depend on the context such as the journal, whether the work is in response toan invitation, or whether this simply represents a preliminary review from a board member before going out more broadly. Critics of this approach emphasize that such reviews are more prone to bias, either negative or positive. One respondent indicated that even if bias is minimal, “since it creates the appearance of bias, it should be avoided.”

The least popular type of review was the public open review, where the identities of the reviewers and the author are known to each other and made public. The strongest advocates of this type of review focused their comments on the benefits of the complete transparency of the process. This would likely make the reviewer more accountable and motivate greater professionalism in the quality of the review. Yet, like other approaches, this would be fraught with challenges. For example, one respondent questioned the appropriateness of acknowledging reviewers as coauthors in cases where the reviewer provides the substantial assistance needed to make the manuscript publishable. Interestingly, the very same issues that make this approach more appealing to some make it even more objectionable to others. Many of the challenges associated with the private open review are exacerbated when the process becomes more public. For example, publicizing the process might spawn reviews that are more superficial, more excessive, or more prone to initiating conflict in the public arena. Perhaps even worse, some respondents suggested this might result in fewer scholars who are willing to engagein the review process.

4.4 Strengths and Weaknesses with the Status Quo

The fifth research question addressed strengths and weaknesses of current peer review processes. First, some of the strengths raised by the respondents will be considered. Almost all of these comments were focused on the double-blind review. Many participants indicated their belief that the double-blind review system is working well. It minimizes bias and provides useful feedback from multiple perspectives that can benefit both the author and the audience. Many indicated that feedback is usually constructive, confidential, and improves the manuscript. They believed that well-qualified and carefully selected reviewers generally provide in-depth recommendations where their expertise is needed and used effectively. They indicated that the double-blind review system helps safeguard quality, ensures academic rigor, and usually produces an appropriate outcome when coupled with effective editorial decisions. Many respondents agreed that while this process can benefit the author through the mentoring that might occur, but they also suggested that reviewers can also grow professionally and benefit from being privy to insights from emerging research trends.

Despite the numerous aspects of current review practice described as strengths, a variety of these same areas were also perceived as weaknesses. For example, 93 respondents (35.6%) lamented that reviewer comments are often contradictory and difficult to process, synthesize, or apply. While inconsistencies across reviewers can be challenging, the conflict may raise awareness of important issues within the manuscript that leads to valuable improvements. These improvements may be based on changes suggested by a reviewer or sometimes they may come in the form of a stronger or clearer rationale provided by the author for particular decisions reflected in the manuscript that do not conform to reviewer recommendations.

Another area perceived both as a strength and a weakness is in the blinding of reviewers and authors. Survey responses show that 127 of the participants (48,7%) would like to see greater transparency in the review process. One skeptical respondent commented,

Behind the protection of anonymity, reviewers may adopt an unprofessional tone that is not constructive. They may also use it to block the publication of research that contradicts their own research or does not agree with their own worldview.One reviewer also mentioned that even mentoring can become much more difficult in a blind process. Another respondent asserted that blinding the manuscript (i.e. in-text citations and references) actually provides more information about author identity than would be available with an unaltered manuscript. Despite what respondents acknowledge as “imperfect,” most respondents see blinding as an infrangible part of the review process, describing it as “essential,” “critical,” and “superior” for minimizing bias and optimizing fairness, particularly for unknown scholars.

An additional area thought of as a weakness by some and as a strength by others is the editorial decision to override the recommendations of particular reviews. With no significant differences across editors, board members, or reviewers (F(2,233)=.033, p=.968), respondents drew from their personal experience to suggest that on average,editors override reviewers for a little more than 23% of the reviews they process (N=237, M=23.369, SD=19.992). Some respondents raised concern for potential abuses that may undermine the peer review process if this decision is made too often or too easily. However, 29 of the respondents (11.1%) not only recognized the need to empower editors to make difficult decisions, but were critical that more editors did not go far enough to countermand reviews that were weak, that lacked adequate support for claims, that were overly harsh or biased, or that were effected simply because they originated from scholars with considerable notoriety.

A final area perceived both as a strength and a weakness is the emergence of various online software systems used to receive manuscripts, manage reviews, and prepare papers for publication. Some authors and reviewers have found these technological resources to be impersonal and frustrating. They struggle as they work across interfaces from different journals, especially when they need to use different credentials to log in and different tools to complete their work. However, most respondents felt that these automated systems have greatly simplified and streamlined the review process. Some editors emphasized that these tools help them better track, select, and evaluate reviewers, thus improving the process and avoiding overburdening frequent reviewers.

4.5 Challenges with Peer Review Processes

Several respondents also identified a number of problems with the current state of peer review. The connection of some of these challenges with the actual peer review process may be less direct though they impact the context in which reviews occur. For example, 22 of the participants (8.4%) in open-ended commentary expressed the concern that there may be too many journals and too many manuscripts to process effectively. Nevertheless, since the number of academic journals and manuscripts in need of review are only likely to continue growing, effective solutions may not be found in attempting to circumvent the number of manuscripts but in better managing the way they are processed.

Another topic that impacts the review process is plagiarism. While this has more to do with certain authors than the review process itself, it impacts the context in which reviews occur and the safeguards used to prevent it. Again, with no significant differences across editors, board members, or reviewers (F(2,230)=.091, p=.913), respondents suggested that, based on their own observations of the manuscripts they encounter, plagiarism occurs about 11% of the time (N=233, M=11.567, SD=10.148). While some reviewers areon the lookout for plagiarism, many see its preclusion as the responsibility of the editors, their boards, or technological resources. As one respondent indicated, “I assume the author has not plagiarized. If there is plagiarism, it is extremely upsetting.” He continued “I do not expect the editor to send me a plagiarized article to review.”

Respondents addressed eight additional problems associated more directly with the review process by indicating the approximate percentage of the time they occur as they have observed them. Table 6 presents seven of these issues and includes the number of respondents, means, and standard deviations. While no statistically significant differences were observed across editors, board members, or reviewers for any of these seven issues, there were significant differences across the problems themselves resulting in three statistically unique subsets:

Table 6: Problems Associated with the Peer Review Process

The first four issues did not differ significantly from each other and highlight the most pervasive challenges. According to the professionals who participated in this study, in nearly 33% of the cases, reviewers believe that they know the identity of the author as shown in Table 6. Moreover, just under a third of the time, these professionals think that reviewers lack the needed expertise to complete the review effectively. Almost as frequently, these results suggest that reviewers accept manuscripts that should actually berejected. These results also show that respondents believe that in about 30% of the cases, studies are rejected because their results are not statistically significant and that about 21% of the time, manuscripts are rejected because they are replication studies. Perhaps a bit like plagiarism, the final two problems mentioned here could be a little more nefarious. The professionals in this study indicated that just in over a fifth of the cases, they believed that reviewers rejected manuscripts because they were critical of the reviewer’s views and that just in under 10% of the cases, reviewers intentionally delayed the review process.

The last challenge was the problem of reviewers rejecting manuscripts that respondents felt should be published. This issue was separated from the table because this analysis represented the first and only case in which differences were observed across the roles of editor (M=26.60, SD=19.86), board member (M=27.42, SD=19.29), and reviewer (M=37.45, SD=24.29), F(2,233)=3.557, p=.030. Responses from editors and board members were virtually indistinguishable, suggesting that, in a little more than a quarter of the cases, reviewers inappropriately rejected manuscripts that should be published. On the other hand, reviewers believed that this occurred in well over a third of the cases, more frequency than was perceived by the editors (p=.022, d=.489).

Four additional areas were examined in terms of their perceived level of adequacy based on a six-point scale similar to the scales used previously. It ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). Though no significant differences were observed across editors, board members, or reviewers, differences were observed across these areas (F(3,1025)=110.616, p<.001). Results are displayed in Table 7, which presents the number of respondents, means, and standard deviations, and shows three statistically unique subsets. The first of these subsets address the adequacy of the number of reviewers. Responses suggest a fairly strong agreement that the number of reviewers has been adequate in most contexts. Inspection of the open-ended comments revealed that a number of participants recommended at least two or three reviewers, with the majority recommending three reviewers:

Tab. 7: Level of Adequacy of Addressing Common Problems in Peer Review

Participants also responded to the statement: the selection process for qualified reviewers is adequately rigorous. This produced a mean between somewhat agree and somewhat disagree, a weak response suggesting potential concerns. The difference between the acceptability of the number of reviewers and the acceptability of the selection of reviewers was statistically significant (p<.001, d=.794). The two remaining problems in Table 7 include the timeliness of the review and publication process, and the adequacy of reviewer incentives, both of which were perceived by the respondents as somewhat inadequate. Compared to the reviewer selection process, where some dissatisfaction was already evident, significant differences were observed both for the lack of timeliness of the process (p<.001, d=.579) and the inadequacies of reviewer incentives (p<.001, d=.696).

4.6 Suggestions for Improvement

The final research question addressed the suggestions respondents might have for improving the review process. Responses to this item were compiled from the open-ended survey question on this topic. Comments on particular themes have been tallied and presented in Table 8, based on their frequency of occurrence. These responses seem wellaligned with other findings, presented earlier, and help substantiate the challenges that may need the most attention:

Tab. 8: Suggestions for Improvements

The most frequently mentioned improvement focused on the need for better recruiting, screening, and evaluating reviewers. Many respondents explained that more and more reviews seem to be done by a small core of scholars. There needs to be a way to identify more qualified scholars who are willing to provide quality reviews. Many respondents also indicated that the expertise of a reviewer is not always well aligned with a particular manuscript and that editors should do better screening of scholars to ensure a good match. On the other hand, editors feel pressure to complete the process in a timely manner and may feel forced into some reviewer choices that may not be as ideal as they would like them to be. This also includes the need for methods of evaluating and eliminating reviewers who may be unable or unwilling to complete high quality reviews within established deadlines.

The next most frequent area for improvement has to do with a number of time constraints. The greatest concern is the excessive amount of time it takes from original submission to publication. Many respondents believe that the turnaround time is absolutely unacceptable. These findings seem consistent with those presented earlier in Table 7. Many authors believe that editors bear much of the responsibility for this, while editors cite difficulties finding qualified reviewers who will complete reviews on time. Reviewers mention their heavy workloads and other priorities that must take precedence over reviews. Some respondents suggest that reviewers will take as long as they are given, so limiting there view time to two or three weeks may improve the timeliness of the process. Other reviewers expressed a desire to provide editors and authors with quality review, but feel that they need more time, given their numerous other commitments. Because of these constraints, many reviewers feel that they have to make difficult decisions between the quality and the timeliness of a review.

Another area for improvement that may be closely related to finding and keeping effective reviewers, who have adequate time to perform the job well, is the need to better incentivize participation in the review process. Many respondents explain that, with their heavy workloads, they have no incentive to engage in the review process beyond their own goodwill. While they would like to contribute more to the field, they cannot do so by neglecting employment obligations. Thus, their participation often comes at a significant personal sacrifice.

While various forms of recognition may be helpful and appropriate, survey responses suggest that what reviewers would prefer is one of two types of incentives. The first is to bepaid directly for their work as a reviewer. The second, and perhaps most appealing, incentive is for the institutions that employ them to credit them for their review work in ways that count towards promotion.

The next area for improvement is a multifaceted category that could be designated as the need for greater professionalism from editors and reviewers. This professionalism, as described by respondents, may take several forms. For example, respondents would like to see much more objectivity from editors and reviewers, where bias and conflicts of interest are minimized or eliminated. Many respondents would like editors to assume a more direct role in establishing and enforcing civil and constructive discourse. Where necessary, they would like editors to uphold an environment in which reviewers must support claims with sound argumentation or relevant literature. When appropriate, they want editors to boldly override unfair reviews, and provide balance to biased commentary. They would like to see reasonable policies consistently applied, including equitable procedures for appealing decisions. Finally, they would like to see greater transparency and better and more frequent communication from the journal throughout the review and publication processes.

Respondents also recommended better training and feedback for reviewers as another important area for improvement.This could include better guidelines and clearer expectations for reviewers. It might also include some type of mentored apprenticeship where new reviewers could be coached and receive feedback. Since some respondents already feel that journals require too much from them in the review process, editors would probably need to be cautious in attempting to implement such procedures. Many participants also expressed a desire to have access to the comments of other reviewers for a particular manuscript as an important form of feedback for their own comments. While this is becoming more common, many believe this should be a standard practice. Since there seems to be a shortage of willing and qualified reviewers, many respondents also expressed the need for the field to better prepare graduate students to transition into the role of a reviewer. Perhaps this could be emphasized more in graduate school or some form of training might be provided in connection with a new scholars first appointment.

The last major area for improvement addressed here is the need for better pre-screening of manuscripts by editors before they are sent out for review. This topic was a bit controversial because a number of respondents expressed concern that editors may wield too much power in rejecting a paper for which they may lack expertise or adequate context to evaluate fairly. More reviewers, however, lamented that editors were too hesitant to reject manuscripts that were poorly written or had fatal flaws. One reviewer said,

The biggest issue I have as a reviewer is spending time on manuscripts that do not deserve the attention. This makes me reluctant to accept future reviewing work.

There were a number of additional suggestions for which room is only adequate for a brief mention. These include better support for non-native speakers, hiring more support staff to ensure that the administrative work of the journal be effective and efficient, helping authors to reach higher quality standards before submitting their work, and increasing venues where quality replication studies and studies without statistically significant findings can be published if they provide meaningful contributions to the field.

5 Discussion

This study has presented a variety of findings focusing on the respondents’ perceptions of the peer review process in Applied Linguistics and its related fields. These include an evaluation of current practices, the various roles of the reviewer, different methods of review, as well as numerous strengths, limitations, and suggestions for improvement. Findings show that satisfaction levels for some current practices in the peer review process are low and that many of the respondents retain a number of concerns they wouldlike to see addressed.

In order to contextualize these concerns, it is helpful to understand how reviewers perceive their role. Most reviewers see themselves as guardians of the discipline, working together with editors for the public good. They believe that their most important roles are ensuring the adequacy of the methods and conclusions in the research they review. Most are likely to agree with a respondent who declared,

The greatest harm that a scientific paper can do is to publish support for a conclusion that is simply false.

They also feel an obligation to carefully evaluate the review of literature and the theoretical implications of the work in addition to helping with the overall improvement of themanuscript. Less important to them are their own professional development or the mentoring that may occur within the process.

Notwithstanding a number of differences in perceptions and opinions among individual respondents, on average, there seemed to be a fairly robust uniformity across the roles of editor, board member, and reviewer. With just one exception regarding reviewer perceptions that manuscripts are rejected more often than they should be, compared to the perceptions of editors, all three groups responded with relative consistency. This could suggest that, while board members and reviewers may not have as much first-hand information as editors, they may be relatively well informed regarding many of the issues editors face.

Despite its limitations, another salient finding of this study is the strong preference for the double-blind review with at least two or three reviewers. While there are a number of voices on the periphery calling for much greater transparency on the one hand or much greater protections for anonymity on the other, the majority of those respondents who participated in this study believe that the double-blind review is serving the field well. Despite the popularity of the single-blind review in many other fields, the findings presented in Table 5 show stronger support for ensuring anonymity through the double-blind review and that blinding authors and reviewers is a better protection against bias than opening the process to greater public scrutiny. They see it as the best balance between needed safeguards and efficiency.

Notwithstanding robust support for the double-blind review, many respondents also have serious concerns regarding the question of how review is implemented and managed. The greatest challenges in the peer review process include the unacceptable amount of time the process takes, the lack of incentives for reviewers, and the need for editors to better screen, recruit, train, and evaluate reviewers. If these principal concerns are considered together, it seems conceivable that providing the right kinds of incentives might also minimize a number of these challenges. For example, effective incentives may make reviewers more willing to be recruited, resulting in a larger pool of qualified professionals. With a larger pool, editors may be better able to screen reviewers and match their expertise with the needs of particular manuscripts. They may also be able to hold reviewers to hirer expectation. This could come in the form of better training and ongoing evaluation. Those that do not meet the standards or that are unable or unwilling to meet established deadlines could be excluded in the future. Thus, the locus of control would likely shift toward the editor, allowing for better controls to meet specific standards.

Such adjustments could also have collateral benefits in other areas identified for improvement. For example, if journals have access to a larger and more qualified pool of reviewers who meet established quality standards, it seems likely that concerns over professionalism, excessive bias, meanness, unsubstantiated claims, and misconduct might also be minimized. This could, in turn, free up editors to focus on additional areas identified for improvement such as effectively pre-screening manuscripts, better educating prospective authors on quality expectations for submitted manuscripts, providing support for non-native English speakers, and so on. While these benefits are merely speculative, they may be worth additional study.

If better incentives might improve the peer review process, it may be worth the effort to identify the best kinds of incentives. Though Squazzoni, Bravo & Takacs (2013: 287) warn that “material incentives” should be avoided for reviewing since they might “undermine moral motives which guide referees’ behavior,” these views do not seem consistent with other scholars (i.e. Kumar 2014) or the respondents in this study. Many participants strongly expressed the belief that peer review needs to be better incentivized, including the possibility of being paid for reviews. While a number of journals have taken various steps to recognize reviewers, respondents see some of these actions as “insufficient,” “minimal,” “trivial,” or “of little consequence.”

It seems that what most reviewers actually want is recognition that counts toward promotion. Though this approach is observed in some areas of the world, for many respondents, reviewing tends to be an extra obligation for which there seems to be no meaningful benefit. While it may be in the best interest of journals to carefully consider the most appropriate ways to incentivize reviews, it would be unfair for this burden to rest solely on them. It needs to be shared. For example, national and international associations and organizations within the field could help promote such expectations. Accrediting bodies could also encourage institutions to develop equitable methods for giving scholars credit for quality and timely reviews. For example, there may be an appropriate way to equate a certain number or quality of reviews with scholarly publication in terms of promotion. The field may benefit if publication and the review of scholarship were placed on an equal footing so both can be appropriately accounted for. Ultimately, these considerations need to find their way to the individual institutions in which these scholars are employed.

Additional challenges that may affect the review context indirectly include the rejection of manuscripts simply because their findings are not statistically significant or they are replication studies. While rejecting these studies seems to be the norm, there may be numerous cases in which the absence of statistical significance or the publication of are plication study may provide greatly needed insight. By setting these kinds of studies aside, with scholars being unable to access them, we may inadvertently distort the realities of phenomena we intend to clarify. For example, the field would not be well served if one study of a particular phenomenon was published because an intervention produced a statistically significant result while six or seven studies of the same phenomenon with the same intervention were not published because no significant results were found. Though journals have every right to carefully select the manuscripts they will or will not publish, we may need another kind of venue for carefully reviewed manuscripts that may contribute to our growing body of knowledge though they lack statistical significance or replicate previous work.

As with all research, there are a number of limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. First, there is the group of respondents. While the intent of identifying and eliciting data from editors, board members, and reviewers was fairly successful, many of the respondents in this study might be considered “insiders” in academic publishing. Responses might have varied if they had come from new scholars or those with minimal experience with the review process. This could be examined in future research. Another area for future study could include a more exhaustive analysis of how best to incentivize the peer review process. There are also a number of related topics that could be examined in further research, such as perceptions of open access journals, predatory journals, and misconduct in academic publishing.

6 Conclusion

The present study has elicited data from editors, editorial board members, and reviewers within Applied Linguistics and related fields. Findings focused on the respondents’ perceptions of the peer review process including views of the status quo, the different roles of the reviewer, different methods of review as well as numerous strengths, limitations and suggestions for improvement. While findings show that satisfaction levels for some current practices are low, this study has generated many suggestions thatmight improve the peer review process.

Though a number of journals in various fields have been moving toward a more open and transparent peer review process, on average, professionals in the field of Applied Linguistics tend to favor the protection of anonymity provided by blind reviews over the potential benefits of a more open process. However, there are many challenges the professionals in study have identified that should be addressed. These include the unacceptable length of time the process often takes, the need for editors to better screen, recruit, train and evaluate reviewers, and the need for better incentives. This paper suggests that effective incentivizing of peer review may ameliorate a number of these problems.

Appendix

References

Berardesca, E. (2015). Open Peer Review: A New Challenge for Cosmetics. In: Cosmetics 2 (2015), 33-34.

Bohannon J. (2013). Who’s Afraid of Peer Review?. In: Science 342 (2013), 60-65.

Bosch, X. (2014). Improving Biomedical Journals’ Ethical Policies: The Case of Research Misconduct. In: Journal of Medical Ethics 40 (2014), 644-646.

Brose Journals. (n.d.): The Linguistic List: International Linguistics Community Online. (http://www.linguistlist.org/pubs/journals/browse-journals.cfm, 24/07/2014).

Chan, D. (2009) So Why Ask Me? Are Self-Report Data Really that Bad? In: Lance, C. E. & R. J. Vandenberg (eds.) (2009). Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends: Doctrine, Verity and Fable in the Organizational and Social Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge, 309-335.

Clair, J. (2015). Procedural Injustice in the System of Peer-Review and Scientific Misconduct. In: Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (2015), 159-172.

Groves, T. (2010). Is Open Peer Review the Fairest System? Yes. In: British Medical Journal 341 (2010), 1082-1083.

Groves, T. & E. Loder (2014). Prepublication Histories and Open Peer Review at the BMJ. In: British Medical Journal 349 (2014), 1-2.

Jadad, A. R. et al. (1996). Assessing the Quality of Reports of Randomized Clinical Trials: Is Blinding Necessary?. In: Controlled Clinical Trials 17 (1996), 1-12.

Khan, K. (2010). Is Open Peer Review the Fairest System? No. In: British Medical Journal 341 (2010), 1082-1083.

Koonin, E., L. Landwber, & D. J. Lopman (2013). Biology Direct: Celebrating 7 Years of Open, Published Peer Review. In: Biology Direct 8 (2013), 1-2.

Kowalczuk, M. K. et al. (2013). A Comparison of the Quality of Reviewer Reports from Author-Suggested Reviewers and Editor-Suggested Reviewers in Journals Operating on Open or Closed Peer Review Models. In: F1000 Posters 4 (2013), 1252.

Kumar, M. N. (2014). Review of the Ethics and Etiquettes of Time Management of Manuscript Peer Review. In: Journal of Academic Ethics 12 (2014), 333-346.

Language and Linguistics (n.d.): Scimago Journal and Country Rank. (http://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?category=1203; 24/07/2014).

Macdonald, S. (2015). Emperor’s New Clothes: The Reinvention of Peer Review as Myth. In: Journal of Management Inquiry 24 (2015), 264-279.

Resnik, D. B., C. Gutierrez-Ford, & S. Peddada (2008). Perceptions of Ethical Problems with Scientific Journal Peer Review: An Exploratory Study. In: Science and Engineering Ethics 14 (2008), 305-310.

Rothwell, P. M. & C. N. Martyn (2000). Reproducibility of Peer Review in Clinical Neuroscience. In: Brain 123 (2000), 1964-1969.

Shamoo, A. E., & D. B. Resnik (2015). Responsible Conduct of Research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Shanahan, D. R. & B. R. Olsen (2014). Opening Peer-Review: The Democracy of Science. In: Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine 13 (2014) 1.

Smith, R. (2006). Peer Review: A Flawed Process at the Heart of Science and Journals. In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 99 (2006), 178-182.

Thurner, S., & R. Hane (2011). Peer-Review in a World with Rational Scientists: Toward Selection of the Average. In: The European Physical Journal B – Condensed Matter and Complex Systems 84 (2011), 707-711.

Triggle, C. R., & D. J. Triggle (2007). What Is the Future of Peer Review? Why Is there Fraud in Science? Is Plagiarism Out of Control? Why Do Scientists Do Bad Things? Is It All a Case of: “All that Is Necessary for the Triumph of Evil Is that Good Men Do Nothing?”. In: Vascular Health and Risk Management 3 (2007), 39.

Tsang, E. W. (2013). Is This Referee Really My Peer? A Challenge to the Peer-Review Process. In: Journal of Management Inquiry 22 (2013), 166-171.

Van Rooyen, S. et al. (1999). Effect of Open Peer Review on Quality of Reviews and on Reviewers' Recommendations: A Randomised Trial. In: The British Medical Journal 318 (1999), 23-27.

Walker, R., & P. Rocha da Silva (2015). Emerging Trends in Peer Review — A Survey. In: Frontiers in Neuroscience 9 (2015), 169.

Walsh, E. et al. (2000). Open Peer Review: A Randomized Controlled Trial. In: The British Journal of Psychiatry 176 (2000), 47-51.

Ware, M. (2008). Peer Review in Scholarly Journals: Perspective of the Scholarly Community-Results from an International Study. In: Information Services and Use 28 (2008), 109-112.

Author:

K. James Hartshorn, PhD

Program Coordinator

English Language Center

Brigham Young University

146 UPC, Provo, UT 84602

Email: James_hartshorn@byu.edu